May 17, 2020

RUBEN VALENZUELA

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Celebrating the Liturgical Music of Healey Willan

May 17, 2020

RUBEN VALENZUELA

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Celebrating the Liturgical Music of Healey Willan

Introduction

Ruben Valenzuela is Artistic Director of the Bach Collegium San Diego, Director of Music and Organist at All Souls' Episcopal Church in San Diego, California, and Choral Director of the La Jolla Symphony Chorus. In this interview with Vox Humana Associate Editor Guy Whatley, he discusses a lifelong passion studying the liturgical music of English-Canadian composer Healey Willan.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Ruben, thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. To begin, how did you become interested in organ, choral, and liturgical music?

I grew up in a musical family, and by the age of six I began piano lessons, followed a few years later by violin lessons. Also, a major factor was growing up going to church. Looking back, I feel as though I spent my entire childhood going to church, singing in choirs, playing for choirs, and later helping to lead the choir in sectionals as needed. Honestly, I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t involved with some form of music making in church.

As my interest in church music grew, I began to seek out the organ, knowing full well that this was the instrument that had to be learned. I distinctly remember borrowing LPs of organ music from my local library. This meant bringing home an array of recordings by E. Power Biggs from the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the complete Bach works played by Walter Kraft. The beauty of the complete Bach set (dull playing aside) was that it came with a lavish booklet of pictures showing historic organs, along with specifications. These records were highly influential and introduced me to much of the Bach organ repertoire for the first time. During my final two years in secondary school, while still heavily immersed in piano study, I began to seriously dabble with the organ and secured a series of modest church positions where I was given the opportunity to play both piano and organ. Looking back, I have only a vague recollection of those early experiences on organ — I suspect they were a complete disaster! Once at college, I left the piano behind and began formal organ lessons, having enrolled as an organ and church music major. From that point forward, it was non-stop church music, and soon after a growing interest in liturgy.

How did you become interested in the works of Healey Willan?

My initial interest stems from three recordings of Willan’s choral music that I bought around 1996; it featured masses and motets written for the Anglo-Catholic parish of St. Mary Magdalene in Toronto, where Willan was Music Director (Precentor) from 1921 until his death in 1968. These first recordings made quite the impression on me; I found it especially striking that some of the music evoked Renaissance polyphony, despite having been written between 1925–1960. Not only was the music beautiful, but there was a strong sense that its foremost reason for existence was to support the liturgy. As my own churchmanship aligns with the Anglo-Catholic tradition, Willan’s music went hand in hand with my fervor for this tradition and its music.

This music responds to a precise moment and purpose. For Willan, this corresponds to the unique musical tradition that he established at St. Mary Magdalene shortly after his arrival in 1921. This included a Gallery Choir on the west end to sing the polyphony, and the Ritual Choir (chant schola) in the chancel choir stalls for the Mass propers and other plainsong (and the parish and Willan’s successors maintained this tradition clear up to the present day). During Willan’s tenure at St. Mary Magdalene, both choirs became vehicles for his music and liturgical aesthetic. Before immigrating to Canada and his appointment at St. Mary Magdalene, Willan’s church music was generally more aligned with the music of Parry, Stanford, Elgar, and the like. Thus, it is the specificity of Willan's liturgical music for St. Mary Magdalene that continues to be one of my principal interests.

I also have a deep admiration for Willan, being the consummate liturgical musician. Despite all of his varied roles, he never left his day to day church work behind. Quite simply, he possessed every quality required of an Anglican organist and choirmaster, including that special brand of British humor and wit! He would often describe himself as "English by birth, Canadian by adoption, Irish by extraction, Scotch by absorption." His organ playing was often described as the epitome of exceptional good taste, refinement, and polish. Willan was the very embodiment of the Edwardian church musician, tracing his lineage back to nineteenth century predecessors such as Samuel Sebastian Wesley, John Stainer, and others.

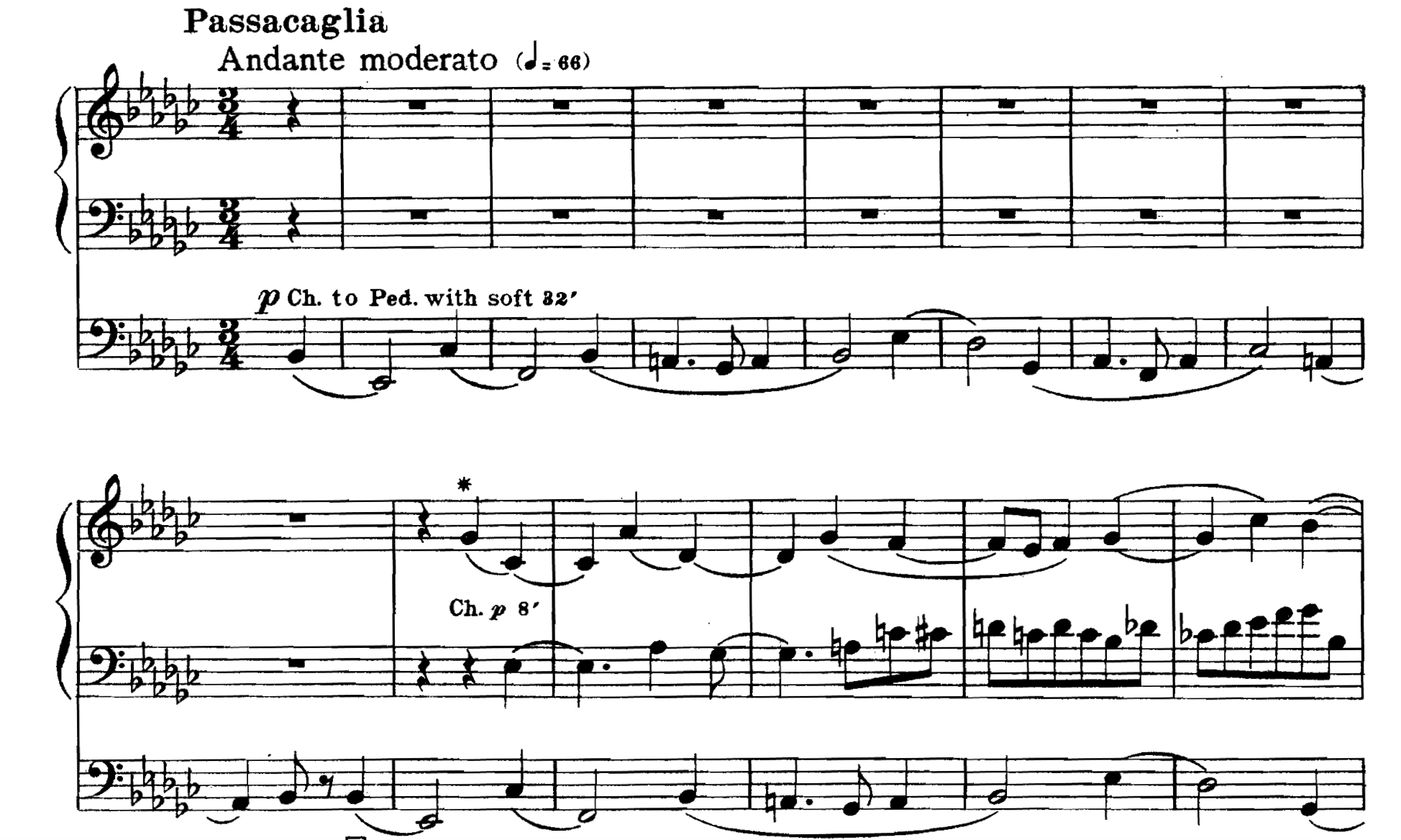

Most organists will know Willan through his monumental Introduction, Passacaglia, and Fugue, a benchmark work written in 1918 for the large Casavant organ at St. Paul’s, Bloor Street:

How does this work compare to his other output for organ?

Supposedly it was written as a response to a colleague's comment that “only a German can write a proper passacaglia!” Beyond the Introduction, Passacaglia, and Fugue, he did also write noteworthy works before arriving in Canada. One example is his Prelude and Fugue in C Minor (1908), cast in the style of Wagner and Reger. This earlier repertoire can be categorized as concert pieces, not particularly designed for liturgical use. By contrast, his sets of chorale prelude from the 1950s are all based on hymn tunes and plainsong, and display Willan’s penchant for creating beautiful miniatures, such as the Prelude (Partita) on St Flavian:

Willan trained as an organist in England, securing his ARCO (Associate of the Royal College of Organists) and FRCO (Fellowship of the Royal College of Organists) at an incredibly early age, Hubert Parry being one of his adjudicators. Willan’s churchmanship was developed out of his experiences as a choirboy at St Saviour’s Choir School, Eastbourne. A few years later and well established as an organist and conductor, the young Willan substituted at several London churches including the well-known All Saints, Margaret Street. Additionally, Willan regularly found his way to Westminster Cathedral to hear performances of Renaissance polyphony and plainsong under the direction of R.R. Terry. These experiences left an indelible mark on Willan and crystallized his lifelong interest in plainsong and polyphony. During this time, he held a close friendship with another young London organist and later very famous conductor, Leopold Stokowski (who became "Uncle Leo" to Willan’s children). In addition to his work as organist, Willan was also a proofreader for Novello & Co., where he once found an errant c-natural in the violin part of the Elgar Violin Concerto, Op. 61, soon after acknowledged and thanked by Elgar himself.

Ultimately, one of the reasons for Willan’s departure to Canada was the need to secure financial stability for his growing family. Once in Canada, part of that security meant taking a lucrative post at Toronto’s largest church, St. Paul’s, Bloor Street (which he held from 1913–1920) which boasted one of the largest organs in Canada, the instrument that inspired the Introduction, Passacaglia, and Fugue. The problem, however, was that St. Paul’s belonged to the "low church" tradition. Despite the lucrative post, Willan’s churchmanship became the catalyst for a move in 1921 to the Anglo-Catholic parish of St. Mary Magdalene. From the time of his arrival at St. Mary Magdalene, Willan worked alongside the Rector, Father H. Griffin Hiscocks to bring their liturgical vision to reality, which was ultimately to advance the liturgy and Catholic ritual. Willan held the post of precentor until his death in 1968, and transformed St. Mary Magdalene into a center for church music and liturgy.

In all this, the organ took a back seat to vocal music. The organ was there to support hymn singing and to provide the liturgical glue through improvisation throughout the mass. The Gallery and Ritual Choir sang exclusively unaccompanied, save for Willan’s accompaniment of the plainsong propers. The organ at St. Mary Magdalene (1906 Breckles and Mathews) was a modest instrument in the English tradition, limited in resources yet effective for the rendering of the Anglican liturgy. Willan was known as a dynamic improviser, and he reportedly used the organ to its potential. At present, this instrument continues in use at St. Mary Magdalene, albeit having gone through some changes and restoration since Willan’s tenure.

In 2018, you organized a year-long festival called Willan West to celebrate music of this remarkable composer. What was your inspiration for this?

Willan West was created to mark the 50th anniversary of Willan’s death and to provide opportunities to hear his choral music in a liturgical context. After considering the amount of music I had in mind, it became clear that the festival would have to run for an entire year in order to perform the bulk of Willan’s masses and motets written for St. Mary Magdalene. Rather than perform the music in a concert setting, I decided the music would be most effective by experiencing it in its original Anglo-Catholic framework, which provides ample space for a mass ordinary, the propers, a motet, hymns, liturgical ritual, and plenty of incense. This framework was graciously supplied by All Saints Episcopal Church in San Diego, where over the course of 14 masses, we aimed to duplicate the liturgical aesthetic and layout of St. Mary Magdalene as much as possible. Each of the Willan West masses featured a Gallery Choir on the west end of eight to a dozen singers, and the Ritual Choir of three to six singers in the stalls at the east end. We made All Saints our home for an entire year during the Willan West Festival, where we held all monthly rehearsals, 14 masses, two Evensongs and Benediction, and two concerts which featured some of his larger choral works. Of the larger works, we had the opportunity to include An Apostrophe to the Heavenly Hosts and Gloria Deo per immensa saecula.

At the core of this festival were the many fine singers. From start to finish over the course of the year, a rotating cast showed an unwavering commitment to offering the music. The monthly routine became gathering on a Friday evening with the Gallery Choir to rehearse the Missa Brevis, the motet, and hymns. Then, return the next day to sing the Mass. Over the weekend of Willan’s birthday in October, we also featured an entire weekend of Willan West activities which included a choral mass at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in Hollywood. Needless to say, over the course of the year we got to know Willan’s style quite well!

Given the importance of liturgical context to this music, in what ways did you emulate the liturgy during the festival?

Most of it stemmed from the Anglican Missal. For some of the masses, we used Psalm tones for the propers, whereas on a few occasions we used the Graduale Romanum as our source, though sung in English. For masses, we never included a Gloria in excelsis, mostly because the once-a-month congregation did not have the opportunity to learn a plainsong setting. Thus, each mass more or less followed this order: Kyrie, Gradual, Alleluia (or Tract during Lent), Offertory proper, Offertory motet, Sanctus and Benedictus, Communion proper, Communion motet, and sometimes a hymn at the end. Most of the time, we used a hymn that pertained to the day’s liturgical observance; sometimes they were written by Willan, including his hymn tunes St. Osmund and Stella Orientis. The entire mass typically concluded with an organ improvisation, a tip of the hat to Willan’s own practice. Here is a video of an Evensong and Benediction at Willan West where we recreated the practice of alternating the Magnificat between two choirs:

Healey Willan: Magnificat: Plainsong Tone VIII.1 and Fauxbourdon (1948), performed by the Willan West choir, conducted by Ruben Valenzuela at Evensong and Benediction on April 29, 2018 at All Saints' Episcopal Church in San Diego, California.

Without a doubt, this festival created an amazing opportunity to immerse ourselves in Willan’s music. I’m forever indebted to all of the singers, many of them close friends, who were incredibly generous with their time to make this a reality. Even with everyone’s busy schedule, we always looked forward to our time together. In addition to Willan’s music, we also included the music of the great Tudor composers such as Parsons, Byrd, and Tallis, in homage to Willan’s own love for this repertoire.

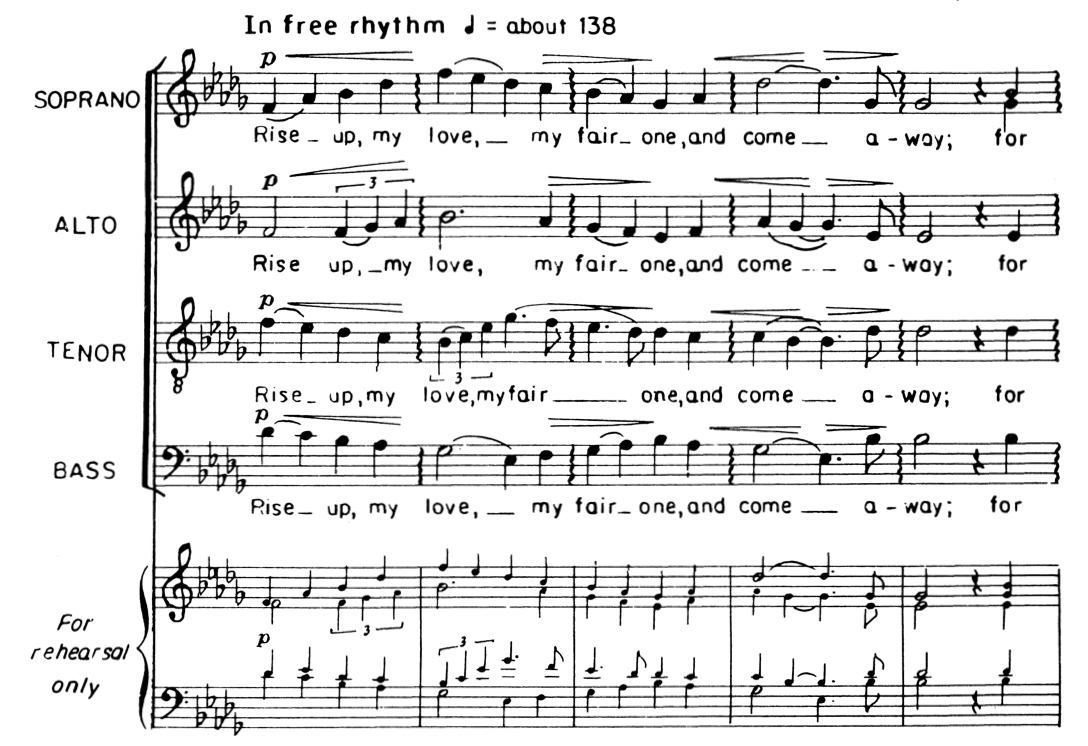

The other key element which made this festival possible was the music’s approachability. His motet Rise Up, My Love, My Fair One is a good example of a sublime miniature. In less than three minutes, Willan establishes an arresting mood which captures the very essence of the text from the Song of Solomon:

Such is the case with Willan’s lesser-known motets: Fair in Face and I Beheld Her, Beautiful as a Dove:

Then, on the opposite end of the spectrum is the Introduction, Passacaglia, and Fugue, or even his very large-scale and resource-intensive Requiem, which is rarely performed. Again, this highlights Willan’s ability to respond to his surroundings and musical resources.

You have written a number of articles about Willan (see below). Where do you go from here with this passion for his music?

There is still so much to do! I go to Toronto once a year to visit what is now family. I’ve had the opportunity to interview persons directly connected to Willan, most notably his daughter Mary, who is now 99! I've also interviewed Willan’s long-time cantor and assistant at St. Mary Magdalene, Albert Mahon, who is still doing very well and is in his mid-90s. Several of Willan’s successors have also shared useful, firsthand knowledge of his legacy and what it meant for them to follow such a towering musician. Although there have been liturgical changes since Willan’s tenure, the overall aesthetic remains the same, with the two choirs and an emphasis on polyphony to capitalize on the warm and resonant acoustic. If I had the time, I would be very interested in producing a short documentary on Willan’s life and music, and quite possibly would entertain writing a book on Willan. At the end of the day, I hope our Willan West efforts displayed a wider scope of Willan’s music, and that there is repertoire to consider beyond the Introduction, Passacaglia, and Fugue and Rise Up, My Love, My Fair One.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Further Willan Articles by Ruben Valenzuela

"Healey Willan, Establishing a Musical Legacy: Willan’s First Decade at St. Mary Magdalene." The Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians 26, no. 3 (March 2017).

"Healey Willan, Fifty years later: The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Death of Healey Willan (1880-1968)." The Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians 27, no. 5 (May/June 2018).

"Healey Willan, Establishing a Musical Legacy: Willan’s First Decade at St. Mary Magdalene." The American Organist, September 2018.

"Healey Willan (1880-1968) The Fiftieth Anniversary of his Death." The American Organist, October 2018.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.