September 16, 2018

CHRISTOPHER HOLMAN

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Mexican Baroque Organ at Tlacochahuaya

September 16, 2018

CHRISTOPHER HOLMAN

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Mexican Baroque Organ at Tlacochahuaya

When thinking about historic organs of the world, the instruments that probably most often come to our minds are the great masterpieces in Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands. And indeed, the organ as an instrument has flourished the most in Europe. However, there are many extraordinary instruments all over the world that are worthy of widespread dissemination. One such organ is located in the middle of the desert in the state of Oaxaca [wa'ha'ka], Mexico, in a small Zapotec farming village called Tlacochahuaya [tih'la'ka'choo'why'ah]. In general, the town is fairly unremarkable, full of cacti, typical desert shrubs, and a few little convenience shops — with the exception of the small but lavishly-painted convent named for San Jéronimo, built in 1558.

Since much documentary evidence about New Spain (especially Oaxaca, due to its remote location) is now lost, we know very little about the origins of the Tlacochahuaya organ. Organs in Oaxaca at that time were often built by indigenous people, perhaps with some guidance from the Spaniards, but it was not until the nineteenth century that we start to see organbuilders' names associated with the instruments. The date 1735 is inscribed on a low bardón pipe, which probably denotes a modification, rather than the building date. At this time, the horizontal reed Clarín 8' was added, and the bardón in question was originally at 4' pitch; the builder made an additional octave of pipes lower. These changes gave the organ an 8' pitch, while before the lowest stop was 4'. Finally, the tambor (a special effect stop that sounds like a drumroll) was removed, and a 4' trumpet (bajoncillo) was installed in its place. Given the decorative characteristics of the organ as compared to other instruments in the region, it was probably built close to 1729.

As in the case of Iberian organs, many instruments in Oaxaca (including Tlacochahuaya) have two drawknobs per rank of pipes: one for the treble, and one for the bass. However, instead of drawknobs, the mechanism for changing the stops in Tlacochahuaya was handles attached to the sliders themselves on the sides of the organ case. Since this made it impossible for the organist to change registrations while playing, a mechanism was later added to make the stops reachable via drawknobs.

The disposition today is the same as it was in 1735, with the break at middle C/C-sharp:

Bardón 8' (bass, lowest octave added 1735)

Flautado mayor 4' (bass and treble)

Flautado segunda 4' (treble)

Octava mayor 2' (bass and treble)

Octava segunda 2' (treble)

Quincena 1' (bass)

Diecinovena 2/3' (bass)

Veintidocena 1/2' — Quincena 1' (bass; Quincena breaks back)

Docena 1 1/3' — Quinta 2 2/3 (treble; Quinta breaks back)

Quincena 2' (bass)

Clarín 8' (treble, added 1735)

Bajoncillo 4' (bass, added 1735)

Pajaritos

Beyond the change in the stop mechanism and the additions in 1735, very little of the Tlacochahuaya organ has since been modified. The exception came during the Mexican Revolution (around 1910–1920), in which the townspeople said that a few pipes were removed and presumably melted down into bullets. In the following years, the organ fell into greater disrepair, until a restoration in 1991 by Susan Tattershall (for more info, see her article on Vox Humana here, assisted by José Luis Falcón and Joaquín Wesslowski with funding from the Pichiquequiti Foundation. During this time a motor was added, though the organ can also be pumped by hand using the original bellows.

The sound of the organ is rather different from what we typically see in at least the famous Spanish instruments from the same period, and it is pitched at A=392 Hz, which is rather low (about a whole step below the modern piano, A=440). Thanks to Loft Recordings, LLC and Robert Bates, we are able to offer the following musical examples, drawn from the third disc of his new recording The Complete Organ Works of Francisco Correa de Arauxo, available via The Gothic Catalog, iTunes, and Spotify. As an introduction, here is a Correa tiento with an Italianate ripieno registration: in the bass is the Bardón 8', Flautado mayor 4', Octava mayor 2', Quincena 1', Diecinovena 2 2/3', Veintidocena 1/2'; in the treble is Bardón 8' and Flautado mayor 4'.

Correa de Arauxo: Tient de medio registro de baxon de décimo tono, performed by Robert Bates.

As you can hear, the acoustics are drier than many European churches. The stops that are perhaps the most different from their Iberian counterparts are the reeds: the small Bajoncillo 4' inside the organ case, and the horizontal Clarín 8'. In this example, we hear the Bardón 8' and Flautado mayor 4' in the bass, contrasted with the Clarín 8' in the treble:

Correa de Arauxo: Tiento de medio registro de tiple, de el mismo séptimo tono, performed by Robert Bates.

In this Correa tiento, the Bajoncillo is played in the bass keyboard, contrasted with the Bardón 8' in the treble:

Correa de Arauxo: Tiento de medio registro baxon de primero tono, performed by Robert Bates.

Finally, to demonstrate the full capabilities of the instrument, here is the Flatuado mayor 4' in the bass, contrasted with all the stops (except reeds) in the treble:

Correa de Arauxo: Tiento de medio registro de tiple de dozeno tono, performed by Robert Bates.

Beyond the incredible sound of the organ, one of its most remarkable traits is the stunning case decoration. Like many instruments in Oaxaca, the Tlacochahuaya organ has "hips" on the otherwise mostly rectangular case — round protrusions on either side that were a characteristic trait of organs in this region from 1686 until at least the late nineteenth century.

The façade pipes themselves are lavishly painted. The bodies are flowers, and mouths are painted with faces; the former is a characteristic unique to Oaxacan organs, but the latter is common in the Iberian Peninsula. Flowers also adorn the base of the instrument, and the boards between the façade pipes feature Spanish Colonial patterns.

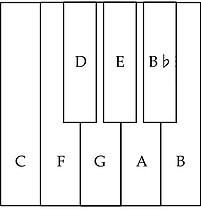

Finally, what repertoire does one play on such an unusual organ? The key action is typical for most historic organs in Iberia and southern Italy — rather light, but still with some resistance before the "pluck." The organ does have a few factors which make conventional literature difficult or impossible. It has no pedal, and the manual has short octave. This means that the lowest octave of keys plays the following pitches:

This was probably done to save money on larger pipes that were rarely used (remember, in that time, the biggest cost of an organ was the material, whereas today it is labor). The Tlacochahuaya organ is also tuned in quarter comma meantone, which, simply put, strives to set major thirds at the beginning of the circle of fifths at a mathematically pure ratio. Unfortunately, dividing the octave in this way results in some keys becoming unplayable. Here’s a recording of me playing major triads around the circle of fifths (C major–G major–D major…):

The circle of fifths in quarter-comma meantone.

As you have heard from the examples, early Spanish music for quarter-comma meantone organs work well: the works of Francisco Correa de Arauxo, Antonio de Cabezón, Sebastian Aguilera de Heredia, Tomás de Santa Mariá, Pablo Bruna, Juan Cabanilles, Antonio Martín y Coll, and beyond. Additionally, most music that works in quarter-comma meantone with short octave is also successful here.

As Cicely Winter, the director of the Instituto de Órganos Históricos de Oaxaca, pointed out in her recent article on Vox Humana (read here), it seems doubtful music by the old Iberian masters was widely played in New Spain, as very few manuscripts of such works survive and many other Oaxacan organs had no music racks. Just a few weeks ago, she released a new edition of her arrangements of Oaxacan folk music that can be played on piano, or an organ like Tlacochahuaya (though not as liturgical music); it will be available internationally shortly.

A few early organ works originally from Oaxaca that can work at Tlacochahuaya do exist. The earliest collection was compiled by Sister María Clara in 1830, but may have been composed around 1800. Entitled, Cuaderno de tonos de maitines de Sor María Clara del Santísimo Sacramento (“Notebook of Psalm Tones for Matins of Sister María Clara of the Most Blessed Sacrament”), the book comprises multiple liturgical pieces for each of the eight tones, many for divided keyboard. Interestingly, there are a number of pieces which are effectively partimenti — bass lines with figures, which are intended for improvisation. A modern edition by Calvert Johnson was published by Wayne Leupold Editions, and is available here.

Despite the instrument's inability to play much literature later than very early Bach, the Tlacochahuaya organ is a testament to organ culture in Colonial Mexico. The characteristic visual designs on the case and pipework reflect the vibrant and cheerful culture that we still see today in this region even today, and the sound of the organ breathes an entirely new life into early music from Spain, Oaxaca, and all of Europe. Since 2000 when Susan Tattershall left Mexico, the Instituto de Órganos Históricos de Oaxaca has overseen care of this wonderful instrument, and in February 2017, André Lacroix of the Gerhard Grenzing firm did some maintenance work on the the organ. Best of all for those in North America, this well-maintained historic instrument is much closer than going to Spain or Portugal!

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Bibliography

Robert Bates. The Complete Organ Works of Francisco Correa de Arauxo, Loft Recordings, LRCD-1141-45 (www.gothic-catalog.com) ℗ 2017 Loft Recordings, LLC. All rights reserved. CD 3, tracks 2, 3, 8, 14. Booklet 54–58, 77.

Cicely Winter. "San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya," Instituto de Órganos Históricos de Oaxaca. www.iohio.org.mx/esp/organos8.htm and www.iohio.org.mx/eng/organs8.htm.

Acknowledgements

The Vox Humana Editorial Board offers our sincerest thanks to Robert Bates and Loft Recordings, LLC (especially Roger Sherman and Victoria Parker) for allowing us to use Professor Bates's new recording of the organ in Tlacochahuaya, now available via The Gothic Catalog, iTunes, and Spotify. The photos were taken by Álvaro de la Paz Franco, David Hilbert, Christopher Holman, and Cecilia Salcedo.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Historic Organs of the World is a new series of short articles on Vox Humana, in which members of the Editorial Board present a less-known organ of historical and cultural significance every month. Articles include information about the instrument's history, photographs, and specification, as well as descriptions of what it's like to actually play the organ — the key action, what the organ sounds like at the keydesk versus in the room, the acoustics, and more, complete with short recordings. Through these tools, Historic Organs of the World seeks to demonstrate how these organs influence the interpretation of repertoire, and raise awareness of the great instruments that have helped shape every aspect of organ art.

Since winning the Albert Schweizer Competition, Christopher Holman has performed on some of the most important historic and modern organs in North America and Europe. He has released two recordings, and his performances have been broadcast on German and Swiss national television and radio. Also active as a scholar, his research has most recently been published in Oxford University’s journal Early Music, and he is Director of Musicology for Bach Society Houston. Thanks to a fellowship from the Frank Huntington Beebe Fund, he is researching and studying historic organs throughout Europe while based at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Switzerland. He studied with Robert Bates at the University of Houston, and Dana Robinson at the University of Illinois. For more information, please visit www.christopherholman.com.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.