November 19, 2017

MARTIN PASI

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Basic Organ Repairs

November 19, 2017

MARTIN PASI

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Basic Organ Repairs

Introduction

Martin Pasi, notable Austrian organ builder now based near Seattle, discusses basic organ repairs and his fascinating journey to becoming an organ builder with Vox Humana Editor Christopher Holman.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Martin, many thanks for agreeing to this interview. Many organists have recently become acquainted with your work from hearing your organ at the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart at the recent American Guild of Organists Convention in Houston. To begin, could you talk about your organbuilding training? How did you get interested in organs, and how did you end up building them?

I grew up in a Catholic church in Bregenz, Austria, where I was an altar boy, and I remember being drawn to — really, in awe of — the sound of the organ. When I was 13 or so, I became more aware of what an organ might be, and how the sound was produced. One day close to Christmas, a priest asked if I wanted to go inside (I hadn’t even conceived that there was an inside!). It changed my life, and from then on, that’s all I wanted to do — look at the mechanics of the organ. With an experience like that, sometimes people go overboard, and might constantly ask if they could look inside the organ, but I was shy. But I looked forward every Christmas to the priest letting me look inside the organ.

When I was 15, I really wanted to become an organbuilder. In Austria, high schools specialize in arts, sciences, etc., and students choose which kind they attend. So of course, I wanted to attend the gymnasium that would get me ready for organbuilding, but my parents talked me out of it. So instead I attended a business school, and afterward I worked in an office for a few years. And I realized that wasn’t going to work for me. When I was 22, I rediscovered organbuilding, and I applied for a post at the Rieger firm, but they didn’t take me on due to an economic recession. But every month I went back and applied, and eventually they figured out I was serious and accepted me into an apprenticeship.

They wanted to educate me to become a voicer because they noticed I had an ear for it, and my skill level kept improving, and they started sending me all over the world for organ installations, which is how I ended up in the U.S. in the end. Eventually, other organbuilders in the U.S. noticed me, and I accepted a job with Dan Jaeckel. I then went to work for Karl Wilhelm in Montréal as a voicer, and toward the latter part of my time there, I equipped his pipe shop and started making pipes and reeds (pipe making was always important to me, I couldn’t stay away from it). While on a job in Portland with Wilhelm, we had a free weekend; I had heard that there were good builders in Tacoma, and I went to visit David Dahl [Professor of Organ (now Emeritus) at Pacific Lutheran University], and he introduced me to Paul Fritts and Ralph Richards. I noticed there was something happening in their shop that didn’t happen elsewhere — the builders weren’t just working, working, working, and producing, but actually talking about organbuilding philosophy and history, and speculating on what historic organs might have sounded like. I wanted to be part of that, and I wrote Paul Fritts, who called me immediately.

So about six months from the time of that first visit, I packed up the family and moved. I was very happy there, and I started discovering the historic organs in Europe — it’s funny, I had to come to the U.S. to do that! You see, when I was younger, the thought in Europe at the time was “we are modern people and we don’t live in the past.” Later on, I had many discussions with [Europeans] about that — how can you not at least be interested?

I’m very glad to have apprenticed at Rieger, because they make every part of the organ, and I gained many skills with them. I really I have to thank Paul Fritts, too, who opened this world of historical organs to me. And finally, about three or four years later from beginning with Fritts, Richards, and Co., everything fell into place to start my own company.

That’s really remarkable! Given that, what organs (historic or modern) have inspired your work?

Before I lived in the U.S., I came to install a Rieger organ in Cleveland, and John Brombaugh at the same time was installing the meantone organ in Fairchild Chapel in Oberlin. He was about three quarters done at that point — and I was completely flabbergasted! It was really a shock to see these American organbuilders, and I knew nothing about meantone temperament. I had also heard Marie-Claire Alain play the organ in Sion [in Switzerland at Valére Basilica, the oldest organ in the world]. So I guess I was really drawn to the “old sound.”

Also influential were Brombaugh’s pupils (Taylor and Boody), and organs inspired by [Brombaugh's] work, particularly St. Alphonsus in Seattle. When I was working in Paul Fritts’s shop as a pipe maker, he began changing to the Schnitger style pipework from the earlier Niedhoff Dutch style. He wanted to find out why they sound like they do, and so we visited Cappel, Grasberg, and several organs in Groningen.

Your rather famous organ at the Co-Cathedral in Houston uses a specialized kind of computerized key action for a portion, but other than that, you only build organs with mechanical action. Why is that?

The simple answer is that it’s what I know, and what I learned! But also, many organists prefer mechanical actions because they can better control pipe speech and articulation, which on electrical action is limited to “on/off.” But for me, philosophically, it was always very clear — the mechanical parts of the organ have a much greater longevity than electrical parts. Also, thinking about the concept and how to execute a mechanical design puts you in a mindset that produces a more intimate kind of instrument for the player because everything is close by. Another benefit to that is that pipes don’t like to be sitting off by themselves all over the place. They need to be together with the others to produce a “melting” kind of sound. If I built an electric action organ, I would lay it out the same way as a mechanical action organ because I’m convinced it makes the instrument sound good, and it will be much better to voice.

Many organists know very little about repairs, especially of the “Sunday morning five minutes before church” variety. How does one properly touch up a really out of tune reed pipe?

1. Pull on a stop that tends to stay in tune (usually a 4’ principal), then the offending reed stop (it doesn’t matter what pitch the reed is in relation to the 4’ principal).

2. Many organbuilders will leave behind a tuning tool, which is usually a 1.5’ long metal stick (but anything similar will work, even a standard butter knife). Take the tool to the pipes and find the offending one. This is usually easiest if you just hold the tool (or your hand) directly over the top of the pipe; when you find the right one, you’ll hear the pitch change.

3. Then hold the tool in the middle and rock it back and forth very gently over the tuning wire. But be careful: if you go too far, you can knock the wire off of the reed! Listen for undulations in the sound — these are called beats. After making an adjustment, if you hear the beats getting faster, you’re going the wrong way. You want to remove the beats altogether, and then that note will be in tune.

What causes ciphers and how does one fix them?

There are many possibilities. Sometimes certain stops will cipher, and then by drawing another stop, it can go away. Try to draw a stop that doesn’t make much sound but uses a lot of wind (like a flute).

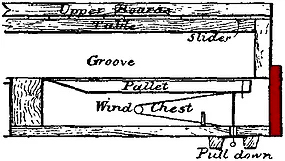

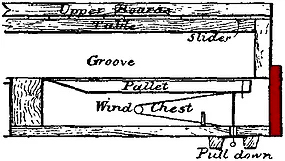

If that doesn’t work, find out which note is ciphering by lightly tapping on each key until you find the note, or you can also use the method as described in the previous question. For standard windchests, turn the blower off and open the bungboard (shaded in red on the figure). Based on the note you found, take a flashlight and gently pull down on the palate, and you might see some dust. After installing an organ, builders will often leave behind a piece of tracker; take that and just knock off the dirt.

For mechanical action organs, you can sometimes just hit the keys with your hand and the cipher will go away. If that doesn’t work, you can also find the regulating point on the organ and adjust it; you can also try to push up on the individual tracker. You can also push up on the square rail.

If none of those work, a FaceTime or Skype call with an organbuilder (or even just text messaging photos) can often lead to a solution. However, the biggest panic is usually due to electronic part failure, which is very hard to fix from afar; to be fair, many times electronics are stable, but sometimes not.

Sometimes reeds will make a buzzing sound. What causes this, and is there a quick fix?

This is usually caused by tiny pieces of dirt that prevent the reed from speaking properly.

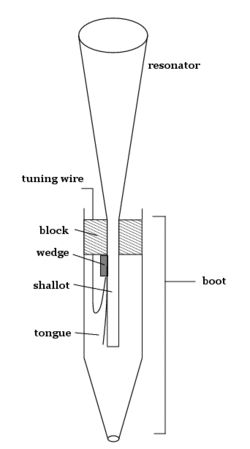

1. Slide the tuning wire all the way to the top.

2. Pick up the pipe

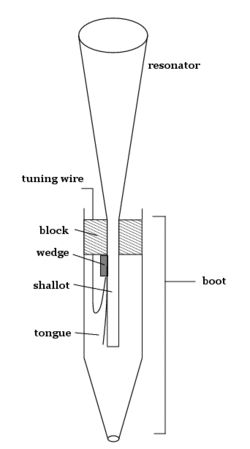

3. Take a dollar bill and put it between the shallot and tongue of the reed.

4. Then put your thumb on top of the reed and slide the bill up and out.

In your view, what is the future of organbuilding and design?

The big question now is how are the huge prices of many organs sustainable? Organs should always be individual pieces, but I’m now working on some sort of “model organ” that could be built continually at a high artistic level and with variation with an “either/or” stop system [where every stop can be played on either manual], but without a huge price tag. My hope is that this could also become a model for future organbuilding generations. I always push for less in an organ than more; people wonder why (because it means I make less money), but artistic integrity is the most important thing, and squeezing more things into an organ than there’s room for doesn’t make much sense.

Are there differences between what's happening in organbuilding in North America and Europe? Are young people interested in the craft, and if so, how does one pursue it?

Many people say that there aren’t young builders. In Europe, parents don’t want their teenagers to pursue organbuilding, and instead to work on academic subjects. And more and more, things are becoming specialized and mechanized/computerized — the trouble is, how do you finish an organ that way? We still need organbuilders, and so we have to train them.

It’s actually much better than it was, say, ten years ago. The Pipe Organ Encounter Technicals have been helpful for introducing people and creating interest. In the last two years especially, there seems to be a lot of interest among young people to go into organbuilding. I’ve had five or six people seriously inquiring at my shop, which is really pretty good! In my case, my daughter is apprenticing organbuilding at Rieger, so hopefully she’ll eventually continue here. I’m trying to recruit younger people so that they can be the start of a completely fresh generation. That being said, some young people can be very enthusiastic but don’t behave in a promising way (“I have all the qualifications and am just what you need at your shop!”). For me, humility is an important quality for serious study. And with apprenticeships by serious young people, I really do think the legacy will continue.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.