November 15, 2020

CHARLOTTE O'NEILL

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll and His Instruments in England

November 15, 2020

CHARLOTTE O'NEILL

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll and His Instruments in England

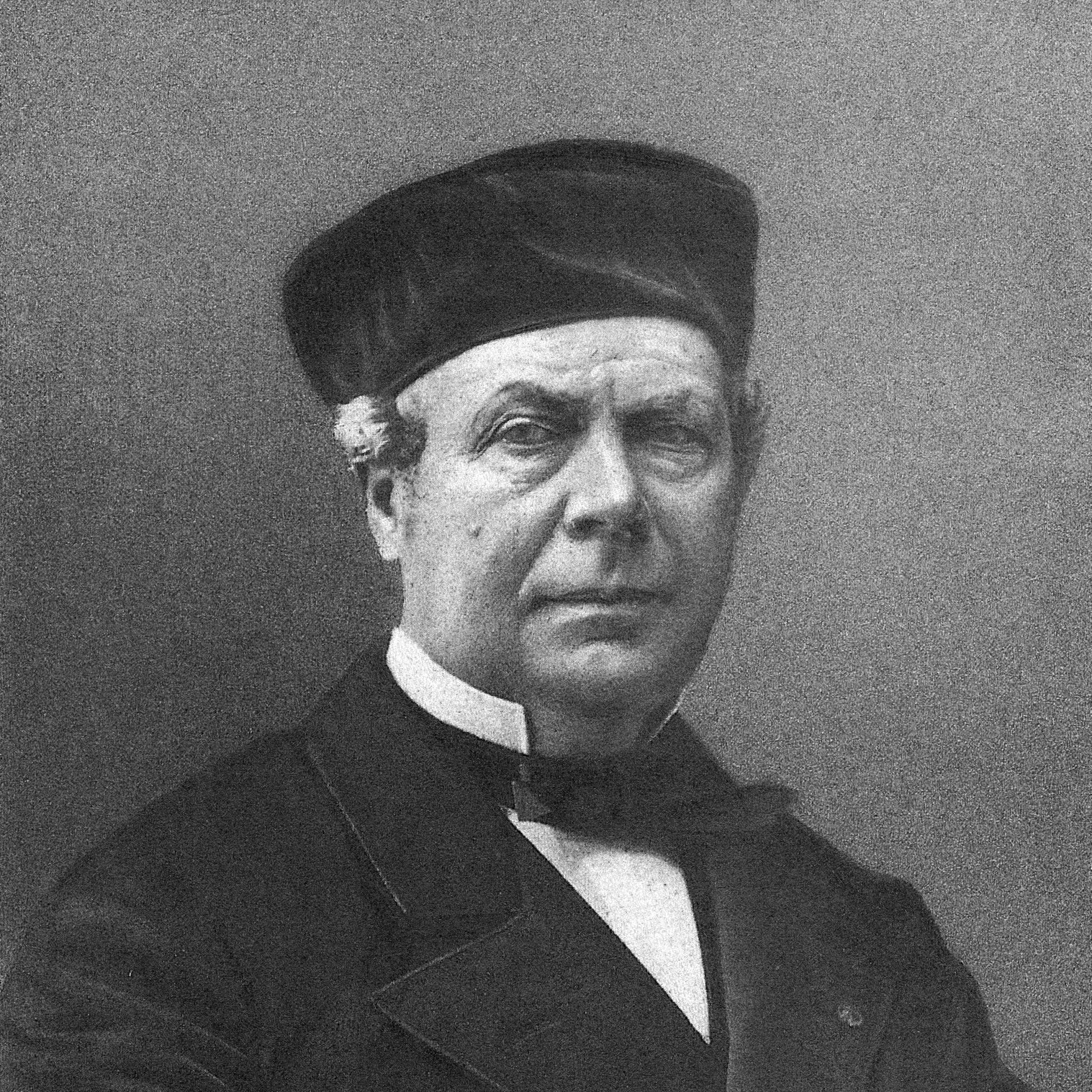

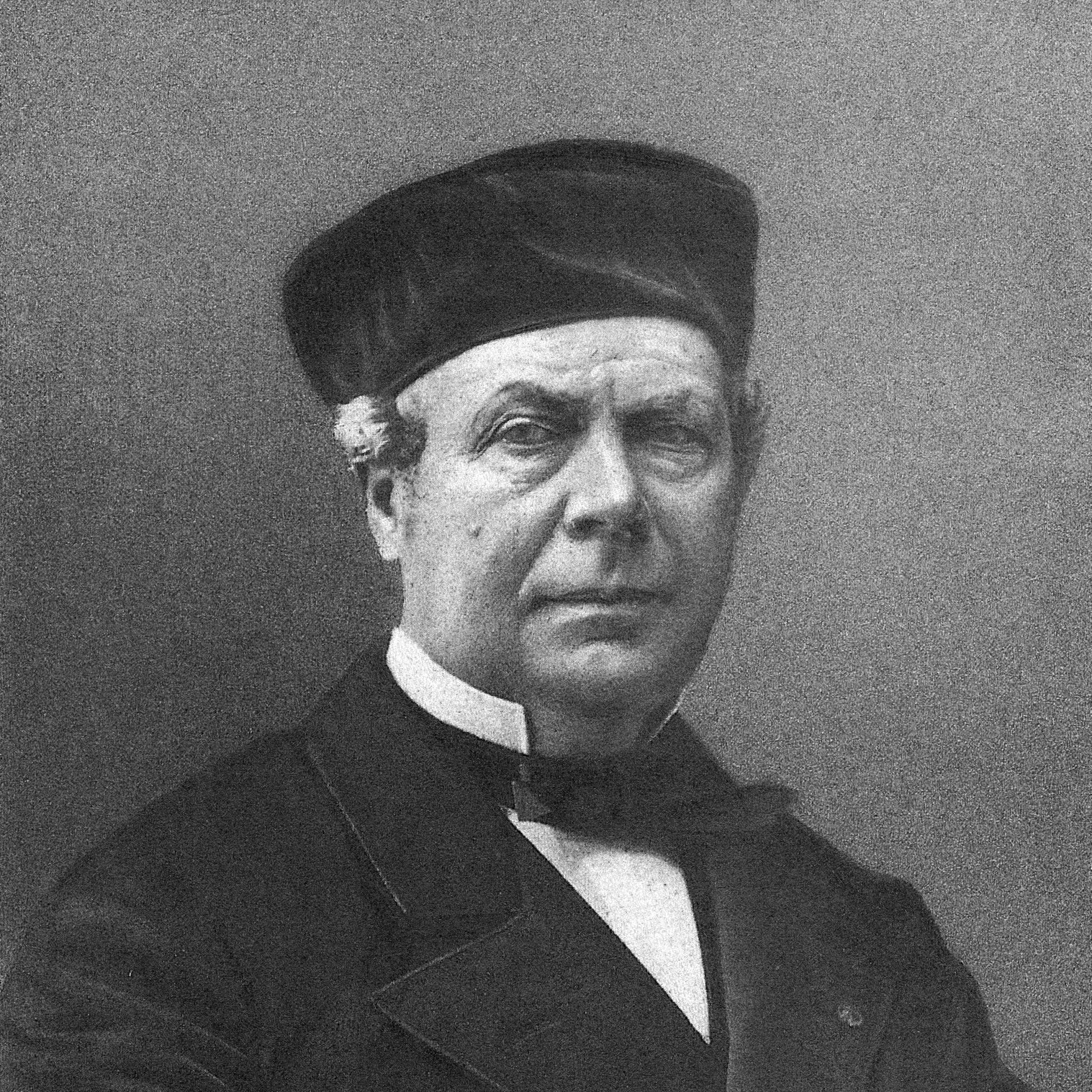

Early Life

Of nineteenth century organ builders, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll is acknowledged as a pioneering figure in construction and development of the modern French instrument. Born in Montpellier in 1811, Cavaillé-Coll came from a long line of instrument makers and organ builders. His grandfather, Jean-Pierce Cavaillé learned organ building from his uncle, the Dominican, Joseph Cavaillé. Aristide's father Dominique continued in the family business, and both Aristide and his brother Vincent were brought up and educated to continue in the field.

When he was five, the family moved to Aristide's maternal home in Spain, where he learned Spanish by reading ‘On prayer and meditation’ by Luis de Granada. His formal schooling ended early, learning woodwork on a scaled down bench in his father's workshop from the age of 11 and becoming formally apprenticed at the age of 14. Although his formal academic career was limited, he was particularly skilled in mathematics, but found literature and Latin dull. He told his own children that having read Don Quixote (Cervantes) and the Imitation of Christ (Luis de Grenada) he "did not see why anyone would read anything else."1

In 1829 at the age of 18, Aristide completed his first solo organ building project, a circumstance brought about by the demand for the family’s skills. His father was needed in a distant town to work on a project there while his brother Vincent was engaged in a second town’s project, so Aristide was left to complete the organ of Lerida Cathedral unsupervised.

In the 1830s he met Rossini, who, much impressed, supplied letters of introduction to leading Parisian musicians and encouraged Cavaillé-Coll to move there. Arriving in Paris he went to visit the mathematician Lacroix who was on his way to a meeting at the Institut de France. So impressed was he by Cavaillé-Coll, Lacroix insisted that he accompany him there. This was to be the start of a long and fortuitous friendship, which also resulted in Cavaillé-Coll meeting another notable mathematician, Henri-Montau Berton on Friday, September 17, 1833. Berton told Aristide about a government contract for a new organ at the Church of St. Denis near Paris, the bidding for which was to close in just three days. Returning home, Aristide immediately began to plan an organ for the church, submitting a full proposal for an 84 stop instrument with stoplists, cost, and renderings just before the deadline.

The St. Denis project, although ratified by the Academy of Fine Arts and accepted by the Ministry of Commerce and Public Works, was controversial and roundly condemned in the local press of the time as a political choice, especially given that Berton sat on the selection committee. Preferred by public opinion instead, was a firm whose work was examinable and at hand. Details of Cavaillé-Coll's plans gave evidence of his competence though: "All vertical rollers shall be made from iron of the proper dimensions, their pivots lathe turned and their bearings of brass and carefully fitted; each part shall be carefully filed and polished." Costs were estimated to be 80,000 Francs and the project to take three years.

As with many major municipal projects, the rebuilding of the church itself was delayed, allowing Cavaillé-Coll time to revise his plan, reducing the specification to 71 stops. He won a second Parisian contract at the end of January 1834 for a new instrument in Notre-Dame de Lorette. Dominique went back to Toulouse to supervise construction there, leaving Aristide in Paris. During the rest of the 1830s the family gradually relocated from Toulouse to Paris, with both father and brother working under Aristide's instruction. Dominique became head of pipe making and titular head of the firm until in 1850 the name was officially changed to "Aristide Cavaillé-Coll et Cie," not the expected "Cavaillé-Coll Pere et Fils."

Contracts followed rapidly: St. Denis Abbey in 1840, St. Omer Cathedral in 1855, and Bayern Cathedral in 1861, among others, with many overhaul and rebuilding contracts. Between 1848 and 1890, the equivalent of a 17 stop organ left the workshop each month.

Each instrument was inaugurated officially, and the ceremony for the 50-stop organ at the Church of the Madeleine had to be repeated two weeks later due to popularity. Aside from official inaugurations, many instruments were tested in the Great Hall of the factory on the Rue de Vaugirard, in an erecting room that was also used for concerts by such musicians as Liszt, Franck, Gounod, Widor and Saint-Saëns.

Louis Vierne credited the mechanical innovations of Cavaillé-Coll with the development of a new form of composition:

"But since the organ was endowed by Cavaillé-Coll with brilliant mechanical improvements that made it a modern instrument, the style of organ literature has followed this progress and the organ ‘symphony’ has made its appearance."2

Technical Advances

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll’s genius was twofold: he had the musical ability to combine in one instrument the tonal colors "previously only known to orchestrators and to combine it with the flexibility to mimic orchestral timbre variation with ease" whilst mechanically embracing advances in technology from other inventors, such as the Barker lever. He also incorporated the acoustic and architectural demands of the installation sites into his plans to ensure his instruments could function at their best. These together with an increase in industrialization more generally enabled Cavaillé-Coll to expand to fill a gap in the market at reasonable cost.

The rise in power driven machinery transformed not only manufacturing industry but also niche markets, of which organ building was one. An increased urban population and the popularity of new churches combined with social reforms led to an increase in leisure time, raising demand for new instruments from both secular and sacred markets. Standardization of parts produced through the factory system also meant that an increasing technical sophistication became possible on larger instruments. Smaller instruments became virtually identical and were marketed via catalogue. Cavaillé-Coll et Cie embraced this trend. Their 1889 catalogue Orgues de tous modeles ranged from a single manual Orgue de Choeur to a 30 stop, three manual version. Another of Cavaillé-Colls innovations was the development of unusual stops such as the Unda Maris 8’ installed on the organ of the Carmelite Chapel in Kensington, London and the Flûte de Pavillon, which appealed to buyers as the epitome of Parisian sophistication.

Cavaillé-Coll’s instruments were specifically engineered to make the most of the buildings in which they were installed. The organ at the church of St. Vincent de Paul in Paris was split into two parts, one each side of the rose window, with the keydesk to one side so as not to obscure the glasswork. The organ at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris included reed divisions that were unusually powerful, a necessity as they were set very high up in the structure which was itself enormously long. Hans Klotz notes that Cavaillé-Coll took "great care over the provision and distribution of the wind supply, using a large reservoir bellows which accumulated the necessary amount of air and smaller adjustable bellows (one for each chest division) to regulate the wind pressure for the various sets of stops."3

Despite such provision for wind pressure, Cavaillé-Coll was still slow to adopt the innovations in motorized winding that were occurring in England, perhaps due to the tendency not to use such high pressures. Typically, pressures were between 80–95mm, a common level for French and German organs of the period, with slightly higher levels for reeds and treble stops than for foundations and bass stops. This could also be attributed to France avoiding the design revolution of the late 1800s, a Cavaillé-Coll organ of 1850 not being dissimilar to one of 1890, either tonally or mechanically. As Bicknell comments "For Cavaillé-Coll an organ with a 32’ stop was a landmark instrument. For Willis, such an organ was commonplace;"4 certainly his suggested plans for many of his instruments in England would support this.

Cavaillé-Coll's concern with wind supply led him to experiment and publish on the topic, winning the respect of the French scientific community. He wrote "The many experiments to which I have devoted myself... have led me to hit upon a new system of regulation which is of great simplicity and which can render useful services not only to the building of organs but also to every manufacturing activity that needs to obtain a constant flow of compressed air or gas."5 Another technique he developed was to use parallel folds in the bellows of the chests, which stabilized the wind flow.

Cavaillé-Coll's experimentation also extended to pipe construction; his Tableau en provenance des ateliers de Cavaillé-Coll lists diameter scales for various stops and details the construction of the Flûte harmonique 8’, which required a hole three sevenths of the way long to make it speak easily.6 He also used a double length version of the same to enhance the power of the treble line.

Such experimentation and refining of manufacturing technique enabled Cavaillé-Coll to build instruments which could produce a long, graduated crescendo/diminuendo with a full orchestral sound at each dynamic level. He did this by distributing the essential parts of the Choir (Grand Choeur) through all the divisions of the organ. This brought into use the trumpets and clarion of the Solo manual (Recit), and as the couplers and swell boxes were controlled by the feet, another innovation, the organist could produce smooth dynamic changes without their hands leaving the console.

The 1870s saw Cavaillé-Coll travel abroad to win contracts across the globe, including Belgium, Italy, South America, and his sole build in Scandinavia (for the founder of the Carlsberg brewing factory). In addition he travelled to the United Kingdom, building several notable instruments and meeting with notable English organ builders of the time, including J.W. Walker and William Hill.

Cavaillé-Coll Organs in England

Cavaillé-Coll’s first instrument in England was commissioned by music publisher John Turner Hopwood for his home in Bracewell Hall, near Skipton, Lancashire. Built in 1870 , the three manual, 34 stop instrument was fitted into the Music Room of the Hall, a space some 62 feet long, 25 feet wide and 30 feet high, occupying the whole of the western end opposite the dining room doors, filling it widthways and up to the rafters. Reports of the inaugural concerts in situ noted that the "pipes are tin, [and] look like burnished silver with a case in the Gothic style."7 Dr. Spark, City Organist of Leeds, played the opening concerts over three evenings, Saturday, Sunday and Monday; the first concert was in the presence of Queen Victoria, Sunday’s programme was sacred music, and Monday’s featured classical organ music. By this point the instrument was well used to illustrious company, having been played by Saint-Saëns and Widor in its first two performances in the workshop hall in Paris and a third time in England by Guilmant.

Christened by the popular press as the "Bracewell Queen," the instrument was later enlarged in 1875 by Cavaillé-Coll, who added three pedal stops and two reservoirs, its air being provided by two water engines. In 1883, Bracewell Hall was sold, and the organ was transported with Hopwood to Ketton Hall in Rutland where it was played once more by Widor, Guilmant, Saint-Saëns and W.T. Best.

The Warrington Corporation purchased the instrument in 1926, where it was installed in the Parr Hall by the Henry Willis and Sons company. It was this same firm who removed the pneumatic Barker levers, converting the action to electric in 1969. To date no tonal changes have been made, and the Parr Hall instrument remains one of the few surviving tonally intact instruments of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. It also retains the manual changeover switch so that the manuals can be played in the usual English order (from closest to the player: Choir, Great, Swell, Solo, Echo, rather than the French order which reverses the lower two manuals).

After the success of the "Bracewell Queen," further orders for instruments came to Cavaillé-Coll from other English towns including Sheffield (1873), Paisley Abbey, Blackburn Cathedral, and Manchester Town Hall. Of these, the instruments in Manchester Town Hall and Paisley Abbey are still extant, that of Sheffield having been destroyed in a fire in 1937. The installation for Blackburn Cathedral was unusual in that it utilised the existing Gothic double case. Paisley Abbey ordered a two manual, 24 stop instrument in 1875 which had 16’, 8’ and 4’ reeds and a III–IV rank mixture. In a major departure from the British swell organs of the time, the Recit contained only 8’ reeds and no diapason chorus.

Disposition of the "Bracewell Queen," now in the Parr Hall, Warrington, Cheshire, United Kingdom

| Grand orgue Montre 16' Montre 8' Bourdon 8' Flûte harmonique 8' Viole de gambe 8' Salicional 8' Prestant 4' Octavin 2' Plein jeu harmonique VI Basson 16' Trompette 8' Clairon 4' |

Positif Quintatön 16' Nachthorn 8' Dulciana 8' Unda maris 8' Prinicpal 4' Flûte douce 4' Doublette 2' Larigot 1 ⅓' (added by Willis in 1972, later removed) Piccolo 1' Echo mixture VI Basson et hautbois 8' Clarinette 8' Voix humaine 8' Tremulant |

| Récit Diapason 8' Viole de gambe 8' Flûte traversière 8' Quintatön 8' Voix célestes 8' Viole d'amour 4' Flûte octave 4' Nasard 2 ⅔' (added by Willis in 1972, later removed) Octavin 2' Mixture VI Bassoon 16' Trompette 8' Clairon 4' Tremulant |

Pédale Soubasse 32' Contrebasse 16' Violon 16' Soubasse 16' Diapason 8' Violoncello 8' Flûte 8' Corno dolce 4' Bombarde 16' Trompette 8' Clairon 4' |

| Accessories Pédales de combinaison Octaves graves Grand orgue L'effet d'orage Appel des jeux de combinaison Pédale. Appel des jeux de combinaison Grand Orgue. Appel des jeux de combinaison Positif. Appel des jeux de combinaison Récit. Appel de mixture Grand Orgue. Appel de'Echo mixture Positif Appel de mixture Récit. Expression Positif; Expression Récit sur Grand Orgue. (Balanced expression pedals) Copula Récit sur Grand Orgue. Copula Positif sur Grand Orgue. Tirasse Récit. Tirasse Positif. Tirasse Grand Orgue. Grand Orgue sur Machine. Copula Récit sur Positif. Annulation anches Grand Orgue. Manual exchange switch (added by Willis) |

There is very little formal academic assessment of the Cavaillé-Coll organs in England. Guilmant, Widor, and others regularly toured England, giving a remarkable number of recitals. Their close relationship with Cavaillé-Coll led them to be invited to inaugurate his instruments here, not just in Warrington but in The Carmelite Chapel in Kensington and in the Albert Hall in Sheffield. Guilmant, Widor, and Saints-Saëns had all tested the Sheffield instrument whilst it was under construction in Paris. Guilmant's comments on Cavaillé-Coll’s building innovations reflect his perception of the status of the organ in both France and England:

"There is a time in which a truly French creation, the modern pipe organ, has reached England. The English, in common with the Germans, have reached a stage where they feel somewhat in the situation of a man who had continued to play the harpsichord, but found himself in the presence of a modern pianist equipped with a concert grand piano."

His praise for Cavaillé-Coll's work was unstinting. He also commented:

"The modern organ such as M. Cavaillé-Coll has created and perfected is a new instrument which requires a new style. At present the true style of the organ is that which, taking the old organ as a basis, gives free rein to the effects of the instrument of today, so rich and marvelous."8

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Notes

1. Michael Murray, French Masters of the Organ: Saint-Saëns, Franck, Widor, Vierne, Dupré (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1998), 20. Return to text.

2. Rollin Smith, Louis Vierne: Organist of Notre-Dame Cathedral (New York: Pendragon Press, 1999), 684. Return to text.

3. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Return to text.

4. Stephen Bicknell, The History of the English Organ (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 257. Return to text.

5. Murray, French Masters of the Organ, 34. Return to text.

6. Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, Tableau en provenance des ateliers de Cavaillé-Coll, manuscript. Return to text.

7. Unnamed author, Musical World, November 12, 1870, 753. Return to text.

8. Orpha Ochse, Organists and Organ playing in Nineteenth Century France and Belgium, (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press), 89-91. "Il y a peu de temps que l’orgue moderne, un creation toutes Francaise, a pénétré en Angleterre. Les Anglais, come les Allemands sont in peu dans le situation d’un homme qui aurait cintinué a jouer du clavécin et se trouverait en face d’un pianiste moderne armé d’un grand piano de concert."Return to text.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Having gained her BA (Hons) at the University of Durham in England,

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.