October 31, 2021

MARIE-LOUISE LANGLAIS

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Organ School of France and the Blind

October 31, 2021

MARIE-LOUISE LANGLAIS

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Organ School of France and the Blind

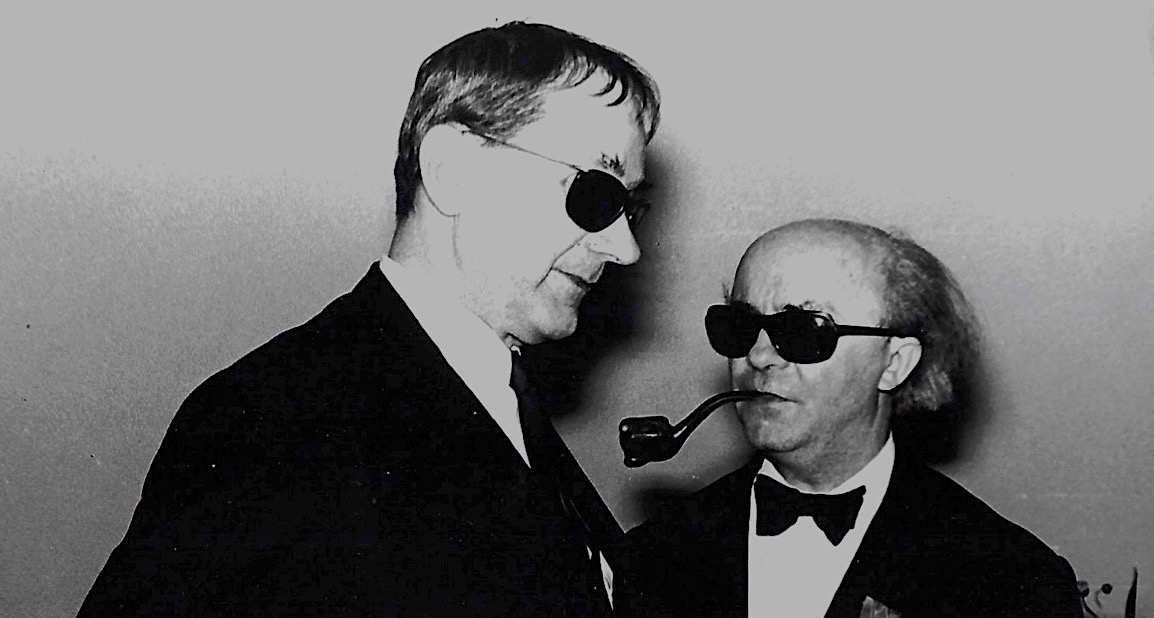

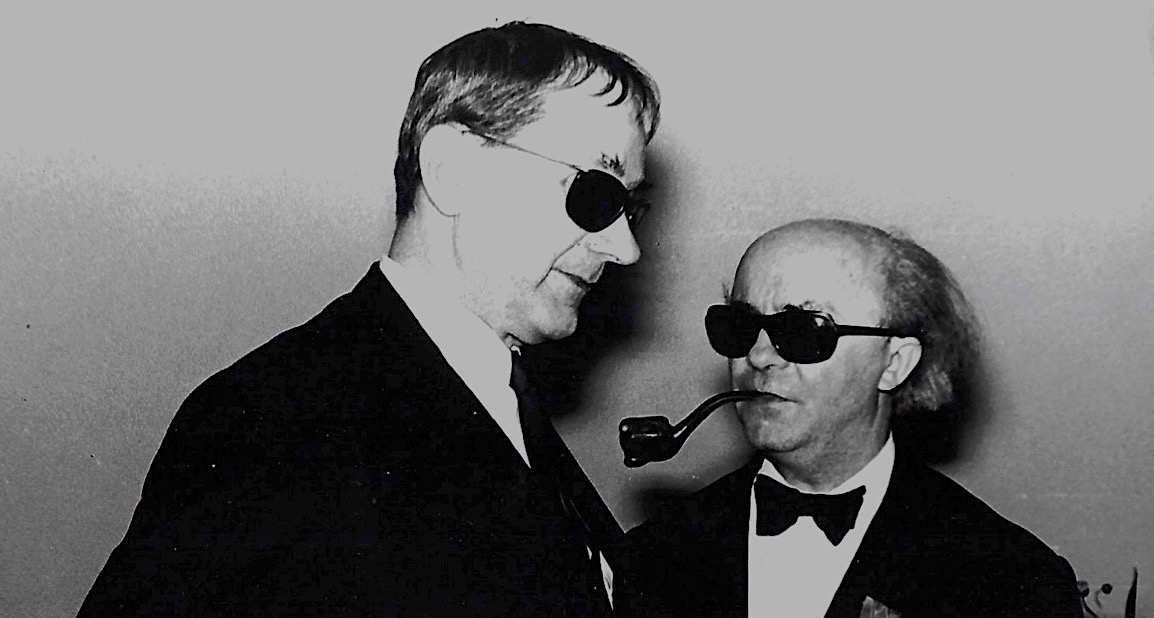

Gaston Litaize and Jean Langlais in 1968, photo by Claude Langlais.

Gaston Litaize and Jean Langlais in 1968, photo by Claude Langlais.

Introduction

In honor of this 30th anniversary of the passing of famed blind organists Jean Langlais and Gaston Litaize, Marie-Louise Langlais traces the intriguing history of the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles, the institution that educated several leaders of France's organ world throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This article has been translated from French by Vox Humana Associate Editor Katelyn Emerson.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Timeless symbols of mendicancy and poverty, the blind have long suffered disdain and been considered the poorest of the poor. Indeed, what could an individual deprived of sight do in life?

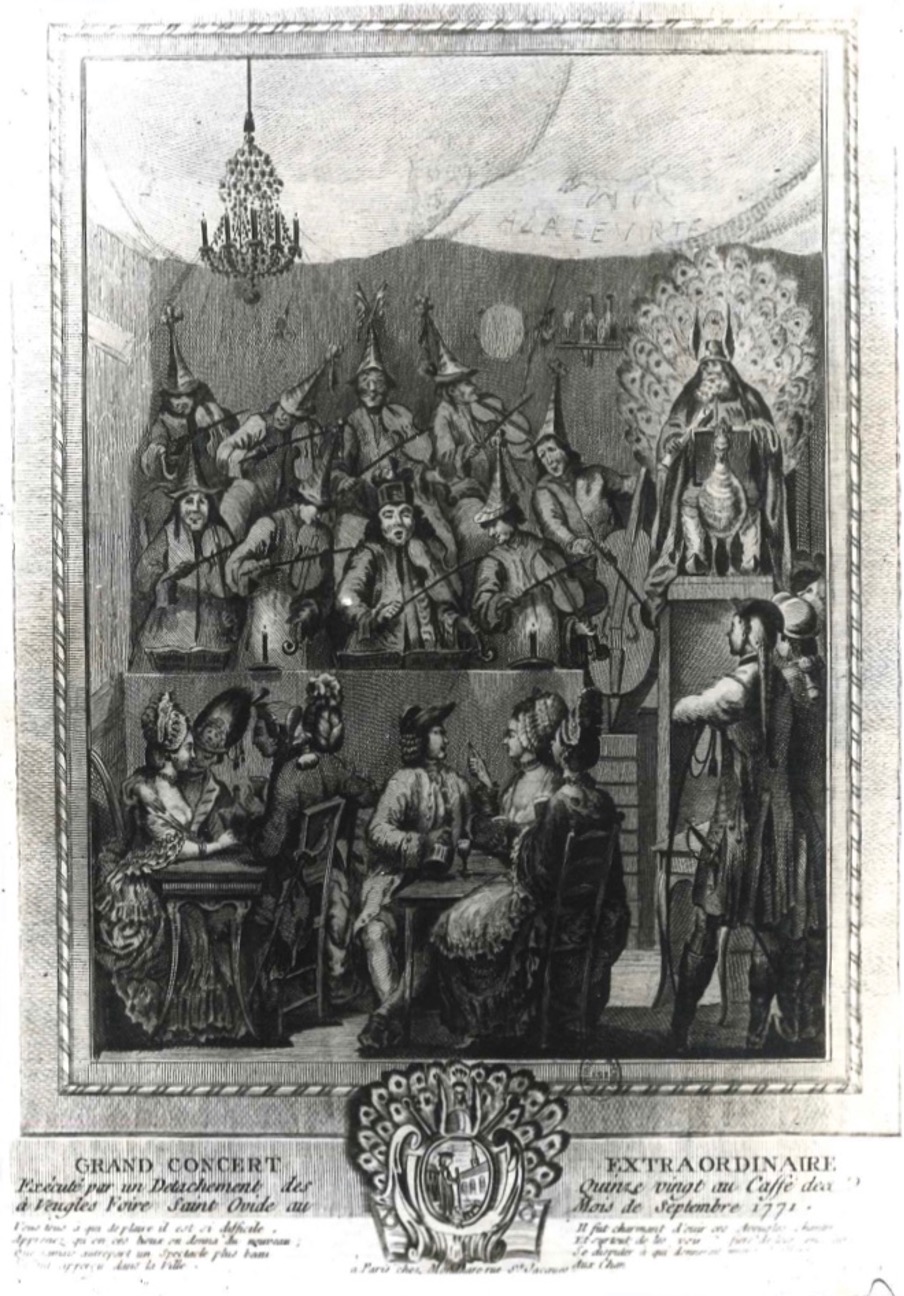

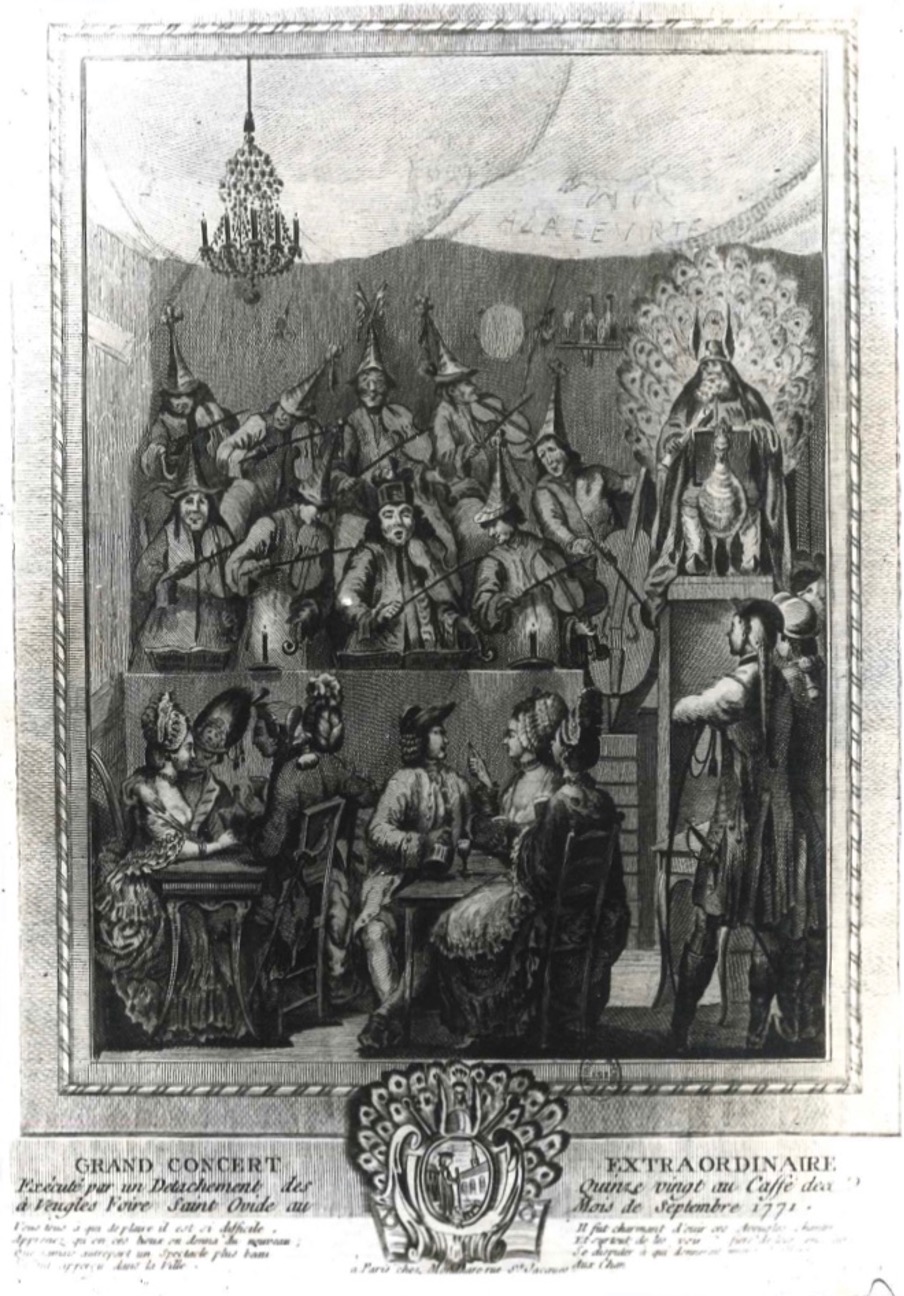

This thought preoccupied French philanthropist Valentin Haüy (1745–1822) when, on a day in September 1771, he passed through the Saint Ovide Fair, which was often frequented by Parisians of the time, and witnessed an outrageous spectacle described in his Essai sur l’éducation des aveugles (Paris, 1786):

“A peculiar novelty captured the general attention at the entrance of an establishment for taking refreshment titled Café des Aveugles (“Café for the Blind”). Rigged out in gowns with long pointed caps and big opaque cardboard glasses, eight or ten poor blind people from the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts stood behind lecterns bearing sheet music, executing a discordant symphony that seemed to stimulate joy in the helpers at table. To round off the farce, someone had placed two lit candles before them.”

Distraught by this degrading sight that had revealed the depth of the inferiority and humiliation to which society had always confined those who could not see, Valentin Haüy decided to dedicate himself to their aid, writing in his Essai sur l’éducation des aveugles:

“I will give truth to this derisive tale and I will help the blind to read… They will trace the characters and reread their own writing. I will put vision at the tips of their fingers. I will ultimately help them to perform harmonious concerts.”

By this time in France, at the end of the eighteenth century, the poorest of the jeunes aveugles (young blind) were confined to the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts in Paris, a kind of charity asylum with hospital resources. Reduced to begging, they tried to pull sound from musical instruments without knowing the music.

Valentin Haüy quickly gained support from the intellectual elite of the day and, because of this, could open a genuine school, the Institution des Enfants Aveugles (Institute for the Blind Children). His work gained recognition when he presented his 24 students to Louis XVI in Versailles on December 26, 1786, when they gave a rather impressive musical performance with choir and small orchestra. Haüy recognized music to be a tremendous tool for the school’s publicity, so he increased the number of concerts over subsequent years, as well as the students’ musical participation in religious celebrations in many Parisian churches (Saint-Eustache, Saint-Roch…). These performances were widely advertised and had a strong impression on audiences of the day.

Alas, the French Revolution in 1789 would soon halt all private charitable sources. The National Assembly retained interest, however, so it nationalized the school under the name of Institution des Aveugles-nés (Institute for those Born Blind). Following the whims of the new political powers, this school unfortunately grew slowly due to meager financial means and constantly changing locations. Nevertheless, musical education always held a prominent place alongside general learning and specialized training for the blind, such as manual work (reseating of chairs, wool spinning). Music was solely taught through memorizing each instrument’s orchestral line and each voice part’s choral line.

After Napoleon I was exiled to the Île Sainte-Hélène and the monarchy returned to France, the Institute, now the Institution Royale des Jeunes Aveugles (Royal Institute for the Young Blind), was once again relocated to dilapidated and unhealthy premises where, according to testimonials, students died like flies.

The Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles in Paris

It finally took the outraged intervention of a horrified parliamentarian, the great poet Alphonse de Lamartine, to prompt construction of large new premises where living standards and teaching conditions would be acceptable and conducive for learning. The new facility was dedicated on October 5, 1843 under the name of the Institution des Jeunes Aveugles (National Institute for the Young Blind). It is located at 56, Boulevard des Invalides, near Les Invalides, and remains in operation today.

Its vast proportions immediately generated enthusiasm in the new occupants. A chapel, constructed in the center to separate the boys’ and girls’ quarters, was designed to respond to musical as well as religious needs. A vast tribune (gallery), designed to welcome a large organ façade, a choir, and an orchestra, enabled symphonic concerts as well as the celebration of mass for the students.

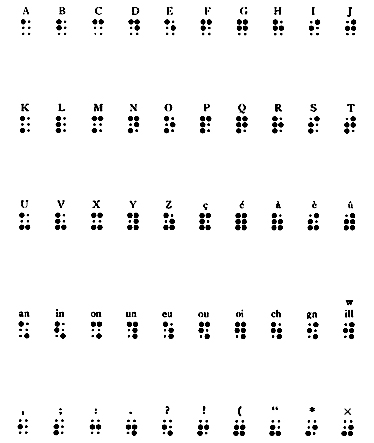

From this moment, the role of music in the curriculum of the blind children became even more prominent. After a prolonged time of political instability, where France had toggled between Republic, Empire, and Restoration of the Monarchy (with Louis XVIII and Charles X), the country yearned for peace and prosperity, which was made possible by rapid industrial development. For these blind children, whose manual work was now pitted against growing mechanization, it became more and more evident that their professional paths would lie through music. Thus, the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles would establish a proper school at the professional level, ultimately becoming a sort of antechamber for the Conservatoire de Paris. However, to accomplish this, a system for reading and writing music that was adapted to those who could not see was urgently needed; a need answered by Louis Braille (1809-1852), who developed the tactile process of reading through embossed dots officially adopted by the Institut in 1854.

For recruiting professors, the successive directors sought to privilege instruction of the blind by the blind, since who better than a blind professor to be a living example that blind students could strive to emulate?

In this time of musical progress, what was the place of organ instruction?

From the 1820s, organ teaching at the Institut responded to financial considerations: at the end of their studies, many students were placed in Parisian churches since, at the time, scarcely any organists in France remained, and very few were being trained.

Because of this, Guillaume Lasceux, organist of Saint-Étienne du Mont in Paris, finding few pupils to whom to pass on his art, consented to donate his organ teaching to the blind students. Immediately, many Parisian churches expressed profound interest in these blind organists and their cheap labor. The modest sums that they received were paid directly to the Institut, providing significant earnings. These young students learned their practical skills “on the job” as they relied solely on their memory to play pieces and chant accompaniments before the Braille system came to their aid. Parisian churches became accustomed to engaging young blind organists to assist and even replace their regular organists.

From the 1830s, under the supervision of Gabriel Gauthier, blind composer, talented organist, Music Director, and successor of Guillaume Lasceux at St-Étienne du Mont, harmony and composition classes at the Institut allowed the musical quality of all the students to expand, particularly that of the organ students. After his passing in 1853, Louis Lebel, a blind organist also appointed to the organ at St-Étienne du Mont, taught organ at the Institut for more than 30 years. He was ahead of his time, teaching the works of Johann Sebastian Bach as well as studies of the full pedalboard, in German style, which contrasted with the studies of the first students at the Conservatoire for whom the organ was nearly deprived of the pedals under the professorship of François Benoist. In 1857, at the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles, Louis Lebel succeeded in convincing his director to commission organbuilder Aristite Cavaillé-Coll to build a small organ for the Institut’s chapel. Initially 18 stops, this instrument would later be expanded to 34 stops over three manuals and pedals and was treasured by the students, as Louis Vierne writes in his Journal (p. 141):

“The new organ in the chapel filled us with joy; it was a very good instrument of three manuals, enclosed in three expressive boxes, therefore possessing extreme versatility; the timbres had perfect distinctness and the ensemble had great impact.”

To increase appreciation for the extraordinary teaching at the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles, successive directors often invited prestigious artists from outside the Institut to preside over end-of-year juries. César Franck was among those invited, as he had succeeded François Benoist in overseeing the organ class at the Conservatoire in 1872. Franck would henceforth wield, alongside Alexandre Guilmant, significant influence over the organ class at the Institut.

Louis Lebel could take pride in having trained a great many organists, among them virtuosos and composers of renown. These included Adolphe Marty, Albert Mahaut, Louis Vierne, and Joséphine Boulay, all of whom entered the class of César Franck at the Conservatoire de Paris and obtained the premier prix in organ. Franck remained extremely interested in these blind organists, fingering 30 Bach organ works in their Braille scores that Breitkopf published from 1861, following the Bachgesellschaft.

The devotion of Louis Vierne for his Maître, organist of Sainte-Clotilde, is widely known, but another blind student, Albert Mahaut, also gives an elegant portrait of him in his book L’œuvre d’Orgue de César Franck, published in 1905:

“Every year, we welcomed César Franck; he came to preside over our competitions, interested in and remarking on everything; it is in this way that I first came to know him. He declared the awards in his deep voice. The voice of Franck! What goodness emitted from that sound! How it stirred us, the blind, who are so sensitive to the nuances of the voice… Franck loved our school. He wrote for us and dedicated his Psaume 150 to us. In our chapel, he directed one of the very first performances of his Messe en la himself, a piece that is so famous today. Our choirs outdid themselves in his presence. Already, we owed him the greatest of our aspirations… the Maître was remarkably good for all of his students; he encouraged me, he loved to show me off, and whenever any significant listener of note would visit, he always called me: ‘Come tomorrow,’ he wrote, ‘and bring your tools’; as he always called my Braille writing implements. I would come, equipped with my tools: he would then dictate a piece of plainchant which accompanied in florid counterpoint. Deprived of my left hand, which was occupied in reading the Braille text, I would add a double line in the pedal, executing the bass with the left foot and the top line with the right foot, both above the right hand. This process always incited great interest. Then, I would improvise a fugue or play one of the great pieces of the Maître.”

Their pater seraphicus was considered a true spiritual guide for the young musicians of the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles, as Louis Vierne write in his Mémoires:

“Franck enjoyed incredible prestige at the school: he was the oracle bringing word from beyond and from whom one awaited judgments with a nearly-fetishist respect.”

Perhaps it will come as no surprise then that, thanks to him, an entire generation of blind composers, improvisers, and organists emerged? In 1886, Adolphe Marty attained the highest award of the Conservatoire, followed by Joséphine Boulay in 1888, and then Albert Mahaut in 1889: this last being awarded the premier prix with his interpretation of Franck’s Prière in C-sharp minor, improvising a fugue d’école and a piece in free-style, as well as accompanying plainchant in four-part harmony with florid counterpoint.

The final resident of the Institut to have been a student of Franck at the Conservatoire was Louis Vierne. Partially blind from congenital cataracts and despite this handicap, Vierne found the career as a virtuoso and a composer completely within his reach, even according to Franck. Unfortunately, Franck died on 8 November 1890, only weeks after the official entrance of this final blind pupil in his class at the Conservatoire. Vierne’s studies at the Conservatoire continued with Franck’s successor, Charles-Marie Widor. Widor particularly admired Vierne, so much so that, in February 1892, he asked him to become his deputy at St-Sulpice, where Vierne remained until his nomination to Notre-Dame. After he received the Conservatoire’s Prix à l’unanimité in 1894, Widor also invited him to assist with his organ class. In 1896, Widor was appointed composition professor, succeeded in the organ classes by Alexandre Guilmant who retained Vierne as official assistant.

A talented new generation, fruit of the tenacity of the successive professors of the Institut and of the generosity of César Franck, was flourishing and lifting the organ school of the blind to the elite level of virtuosos on this instrument of pipes.

At the end of the nineteenth century, many prestigious Parisian galleries were held by unsighted organists: Louis Lebel at St-Étienne du Mont for 35 years until his death in 1888, Adolphe Marty at St-François-Xavier from 1891 to 1930, and Albert Mahaut at St-Vincent-de-Paul where he had succeeded Léon Boëllmann. Presently, Louis Vierne was appointed to Notre-Dame of Paris in 1900 after having faced two other candidates, including his blind colleague Albert Mahaut.

In the academic curriculum of the Institution Nationale des Jeunes Aveugles (INJA), the reins were firmly held by two young blind musicians from the class of Franck at the Conservatoire. Adolphe Marty (1865–1942), the first blind student to obtain the premier prix in organ from the Conservatoire, was professor of organ at the Institut while also fulfilling the functions of music director at the chapel from 1905 to 1930. A prolific composer and inheritor of the Franck tradition, he trained over 300 organists at the Institut, among them Louis Vierne, André Marchal, and Gaston Litaize.

Albert Mahaut, another musician of grand scope, inherited the Institut’s harmony class and devoted the majority of his life to promoting the organ works of Franck through his writings, his lectures, and his concerts, commencing this undertaking on 28 April 1898 with a recital on the gigantic Cavaillé-Coll of the Trocadéro in Paris before 5,000 enthusiastic listeners. Critics came in droves to praise the young virtuoso. According to A. Bruneau, of the daily Parisian newspaper Le Figaro:

“M. Albert Mahaut, a blind organist of St-Vincent-de-Paul and student of César Franck, had the idea of bringing the organ music of his Maître to the public at the Trocadéro, which no one before had yet thought of doing (…). This man lit his eternal night with the dazzling light of sounds.”

Beside these two pillars of teaching at INJA also stood a woman, Joséphine Boulay. Premier prix of organ in the class of César Franck, she taught harmony and composition for 35 years to the blind female students. However, despite her skill, she did not hold any posts as organist and rarely performed in concert, primarily due to her gender. She was nevertheless among, alongside Marty and Mahaut, an elite in the world of blind musicians called to train countless brilliant pupils.

The assistant of Guilmant in the organ class of the Conservatoire since 1896, Louis Vierne took charge of a group of exceptionally brilliant young students among whom was Augustin Barié, also blind and trained by Adolphe Marty at INJA. Organist of Saint-Germain des Prés in Paris and professor of INJA, he died prematurely of a stroke at the age of 31, leaving behind some organ works of great magnitude, notably Symphonie pour orgue, Op. 5, dedicated to Louis Vierne and premiered by André Marchal in 1922.

André Marchal (1894–1980) was another great blind organist whose career stretched throughout much of the twentieth century. Admitted to INJA in 1903, he was student of Adolphe Marty and of Albert Mahaut. Especially gifted, he demonstrated strong pianistic abilities, to such an extent that he initially considered pursuing a carrier as a pianist before he entered the organ class of the Conservatoire in 1911 as the first student of Guilmant’s successor, Eugène Gigout.

André Marchal received his premier prix in Gigout’s class in 1913 and became his deputy at the Église Saint-Augustin before, in 1915, succeeding Augustin Barié in the gallery of Saint-Germain des Prés. He retained this position until 1945, when he was be appointed organist of Saint-Eustache.

Later dubbed “the blind man with fingers of light” (“l’aveugle aux doigts de lumière”), André Marchal had a dazzling international career and, in addition to his improvisational gifts, he helped to establish a new aesthetic of the organ, the “neoclassical”, an outcome of his acquaintance with the organbuilder Victor Gonzales and the musicologist Norbert Dufourcq. The organ and early music were not yet topics of interest in the early twentieth century, but the work of Marchal on touch, phrasing, and the rediscovery of early music, especially that of the French Classical masters, would soon captivate his listeners. From 1925, his career gained international scope, with multiple foreign tours as well as a series of concerts in the USA and Canada in 1930. Thus, a few years after Vierne, a blind organist once again triumphed in America. At this time, the craze for French organists was pronounced across the Atlantic. Among the pioneers of these trips were Alexandre Guilmant (first tour in 1897), Joseph Bonnet (1917), Marcel Dupré (1921), and Louis Vierne (1927). André Marchal returned to the United States no fewer than 18 times.

Appointed professor of INJA in 1919, Marchal quickly became the equal of his colleague and former teacher, Marty, and had among his first organ students Jean Langlais (1907–1991). Thus, the next generation was assured in the world of blind organists, even more strongly when, at the same time, in Adolphe Marty’s class, another young talent revealed itself: Gaston Litaize (1909–1991). Through his teaching, his reputation, and his novel ideas, Marchal succeeded in granting great prestige to the organ class at INJA, opening it to the outside world. Jean Langlais and Gaston Litaize imitated him and their talent as virtuosos, improvisors, and composers was soon talked about. In 1938, André Marchal was first to perform a work by his young disciple Jean Langlais, La Nativité (from Poèmes évangéliques), in the United States. Following this, Bernard La Berge, manager of the North American tours of Louis Vierne, Joseph Bonnet, Marcel Dupré, and André Marchal, came to listen to Jean Langlais in person on the organ of Sainte-Clotilde — and hired him for a first USA tour in 1952. For over 30 years, Langlais traversed the Atlantic regularly to play and to teach, giving some 300 organ recitals overseas. Antoine Reboulot, another student of André Marchal and premier prix of organ in Marcel Dupré’s class at the Conservatoire de Paris, succeeded André Marchal in the gallery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés before establishing himself in Québec in 1967, where he had a brilliant career as organist, pedagogue, and lecturer. He trained numerous students as professor at the Université Laval and then the University of Montreal. On their part, Langlais and Litaize were both appointed organ professors at INJA like André Marchal before them, supervising the studies of many blind students such as Jean-Pierre Leguay, composer appointed co-titulaire of Notre-Dame of Paris in 1984, or Louis Thiry, professor of the Conservatoire de Rouen. All these maîtres also taught in educational institutions for the sighted, Vierne and Langlais at the Schola Cantorum in Paris and Litaize at the Conservatoire de Région de Saint-Maur. Georges Robert, organ professor at INJA and then at the Conservatoire de Versailles while holding the post of organist of the cathedral of the same city, completes this list of organists from the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles.

How much has passed since, in 1771, Valentin Haüy attended that grand concert of a few blind people from the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts in the Saint Ovide Fair in Paris!

In fewer than two centuries, the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles of Paris, having triumphed over an endless series of difficulties, became one of the most important centers in France for organ education, an antechamber for the Conservatoire de Paris, and a rival of better-established private institutions such as the Schola Cantorum.

However, when Jean Langlais and Gaston Litaize retired from the Institut in 1967, they already sensed that there would be no viable continuance to this exceptional journey. New laws concerning the blind and a succession of non-musician directors from the public health administration guided the school towards avenues besides musical ones, aided by the rapid development of computers. As a result, this royal legacy of extraordinary blind musicians will gradually die out…

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Born in Casablanca, Morocco in 1943,

Marie-Louise Langlais began a career as professor of organ and improvisation in 1974, successively at the Conservatoire National de Région in Marseille, at the Schola Cantorum, and at the Conservatoire à Rayonnement Régional in Paris. She has taken part in several jury competitions, both national and international. Beginning in the 1970s, she has written numerous articles for French and foreign journals, with the principal theme of French organ music, particularly “The tradition of Sainte-Clotilde: César Franck, Charles Tournemire and Jean Langlais.”

In 1992, Marie-Louise Langlais earned the Doctor of Musicology degree of the University of Paris IV-Sorbonne with a dissertation on the life and music of Jean Langlais, a condensed version of which was published by Éditions Combre in 1995 under the title Ombre et lumière, Jean Langlais (1907–1991) [“Shadow and light, Jean Langlais (1907–1991)”]. She was awarded the special Bernier Prize of the Institut de France for it in 1999. For the centenary of Jean Langlais’s birth in 2007, Delatour France published her CD of the composer’s Souvenirs. In 2009, to show her admiration for the great French composer Jean-Louis Florentz, she united various testimonies and analyses in a book-CD called Jean-Louis Florentz, l’œuvre pour orgue, témoignages croisés (Éditions Symétrie).

As a concert organist, she has toured extensively, giving conferences and master classes in North America and Europe, and has recorded for different labels: Arion, Delatour, Lyrinx, Solstice, Festivo (Netherlands), Koch International and Motette (Germany). Between 2012 and 2016, she was Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music at Oberlin College (Ohio) three times at the invitation of Professor James David Christie, to share with his brilliant students a certain tradition of the French organ school.

Marie-Louise Langlais takes care of the official website of Jean Langlais (here) and is currently focusing on writing and publishing musicological works, many freely available online as PDFs here, notably free scores by Jean Langlais, recently published; additionally available are Éclats de mémoire, the transcription in French of the unpublished Mémoires of Charles Tournemire in 2014, and in 2020, an English translation of it, Charles Tournemire Memoirs. Also in English, Jean Langlais Remembered, an evocation of the life and works of the composer, became freely available in 2016 on the website of the American Guild of Organists here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.