September 9, 2018

MICHAEL HUFFINGTON, PT, DPT

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Postural Considerations for Organists

September 9, 2018

MICHAEL HUFFINGTON, PT, DPT

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Postural Considerations for Organists

Engraving by Christoph Weigel, Musicalisches Theatrum, Nuremberg: 1722, vol. 1, p. 3.

Engraving by Christoph Weigel, Musicalisches Theatrum, Nuremberg: 1722, vol. 1, p. 3.

Author's Preface

The information in this article discusses the “average” body, and should also be informative to those who have major orthopedic considerations. Individuals, however, are individual and may need to work with a physical therapist or a performance coach to uniquely optimize their personal body mechanics.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Nearly all keyboardists have had it drilled into them that they are supposed to sit with "good posture" while they are at the keyboard. Good posture is synonymous with good balance, and is a critical component in achieving the lightness of hand and foot to play the most technically challenging pieces, and without acquiring a host of repetitive use injuries like neck or back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, or shoulder impingement. Unfortunately, surprisingly few people actually know what “good posture” even means, let alone whether they are achieving it. The purpose of this article is to help the keyboardist easily understand what “good posture” is and how to train yourself to achieve it.

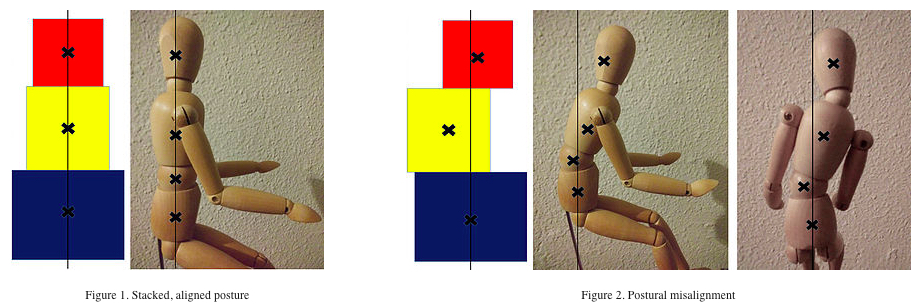

Loosely defined, “good posture” is the posture in which the alignment of the body is optimized. There should be no specific points of mechanical stress in the system, and maintaining your upright balance should require minimal effort. This optimal alignment is achieved when the center point of each body part is centered on the center of gravity of the body as a whole. Basically, if each body part as is a block, the center points of each block should all line up, creating a stable structure. If looking from the side, these blocks would line up front-to-back, and from the back, they would line up side-to-side.

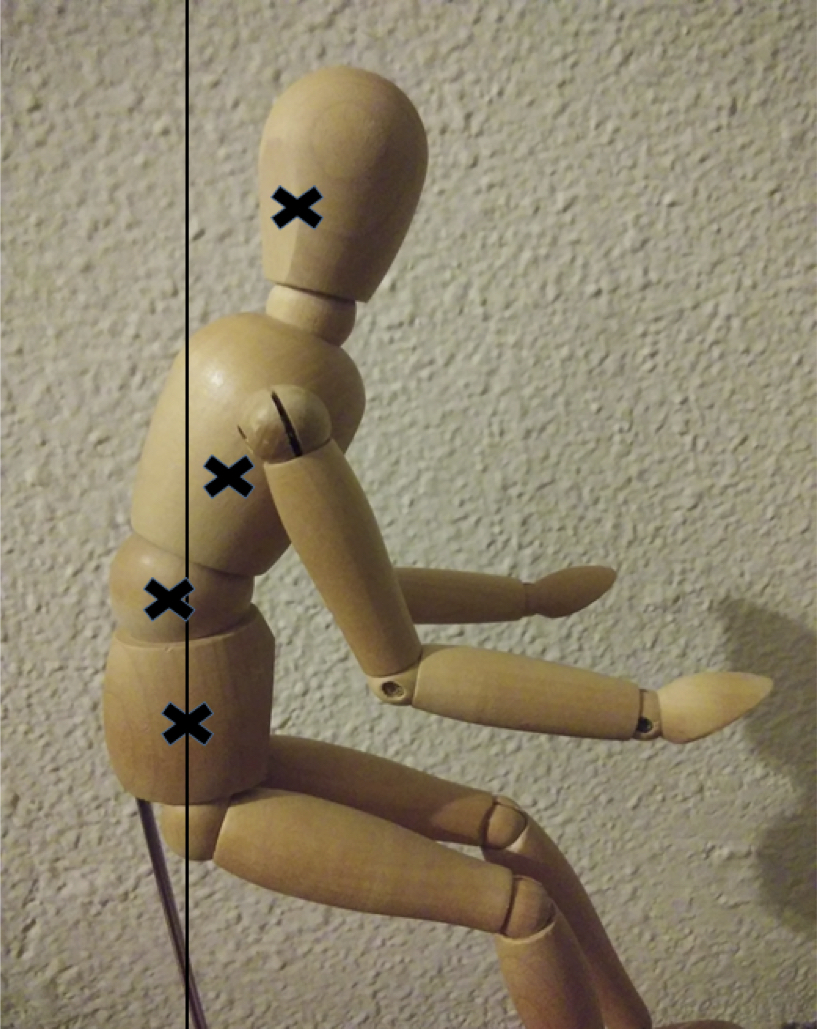

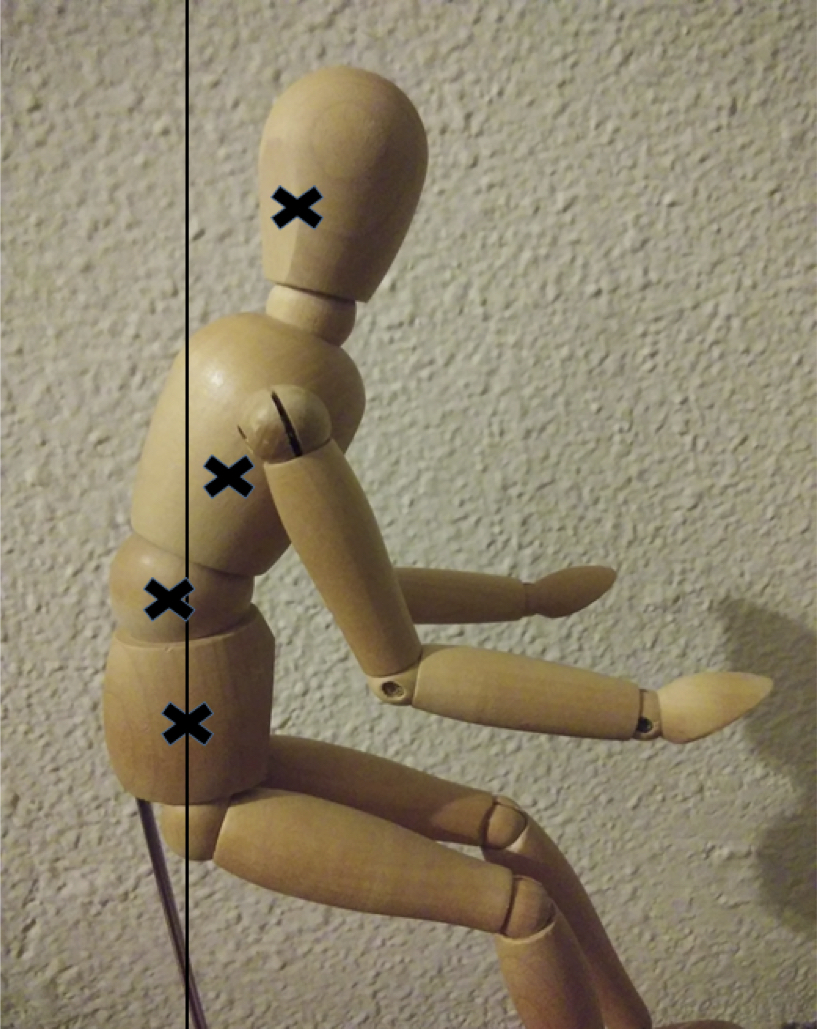

In Figure 1, our “organist” is demonstrating neutral posture, in which you can see that the center point of the head, thorax and abdomen are vertically aligned on the center of mass of the pelvis, which is our base “block” when we are sitting. In Figure 2, though, he is demonstrating how none of the blocks is are vertically aligned with the pelvis when he is slouching or leaning.

In standing, our base “block”, obviously, is our feet. Our spines naturally have an S-curve to them, which helps us both to stay balanced over our feet and also to absorb shock as we walk, run, and play, much like a spring. Notice how in Figure 3, if we extend our vertical line drawn through the center of mass of the pelvis, abdomen, thorax, and occiput, it falls at the arch of the foot. Mechanically speaking, arches are load‑bearing structures. Therefore, anatomically speaking, your body weight should be centered over the arch of your foot if your posture is well balanced.

Organists, however, are sitting on their butts rather than standing over their well-designed, load-bearing feet. Because the bones at the base of the pelvis that we sit on are round, sitting on a bench without a backrest is essentially a balancing act (see Figure 4). In that position, we are always trying to achieve the proper vertical alignment of the pelvis, which is now acting as the base for the head, thorax and abdomen. To find your balance on your "sitʺ bones, put your hands on your waist so you can feel your hip crest, and roll your hips forward and backward until the crest of the hip is parallel to floor, as demonstrated here:

Since, clearly, one determinate of good posture is core strength, here is one simple way to test if yours is adequate:

Once found, your balance in sitting is generally maintained by your “core” muscles and having your feet grounded on the floor. Both the organist and, to a lesser extent, the pianist are pedaling with their feet, which means that the deep core musculature (your pelvic floor and lower abdominal muscles), has to be extra strong to compensate for this lack of groundedness. Generally speaking, people with inadequate engagement of the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles will roll backward on their hips and sit on their tailbone in a slouched posture. Rather than stacking your body over your base, the weight of your body is hanging on your spine and the weight of your hands is hanging on the keyboard (see Figure 5). This rounded posture puts a great deal of pressure on the intervertebral discs in the neck and low back. Additionally, it points the shoulder girdle downward, limiting mobility for reaching, and sets up the classic pathomechanics for shoulder impingement:

On the other hand, many people think they have good posture based on their efforts to be as straight as possible. We attempt to correct our posture or “straighten up” by pulling our shoulders back, rolling the hips forward and trying hard to straighten the spine. The spine, however, is designed to be a shock-absorbing “S” shape, not a rigid pole. Overextending the spine this way results in the center mass of the head and lumbar regions sitting forward of the pelvis, as our keyboardist is demonstrating. With these good intentions and efforts to sit straight, you will be rewarded by excessive back and neck tension and postural fatigue as your muscles work hard to try to keep you from literally losing your balance and falling forward. Your hands will be necessarily heavier on the keyboard, increasing the amount of force at the hand, wrist, shoulder and neck. You will also hinder your potential pedaling speed since the hip flexor muscles are busy working to hold yourself forward of your natural balance point.

Instead, focusing your postural efforts at your base, as the video describes, to find the balanced, vertical alignment of the pelvis will allow the relaxed natural S-shape of the spine to follow, and minimize the intensity of the repetitive forces through the hands and shoulders. You will achieve a stable base of support which allows maximal freedom of movement of the arms, legs, hands and feet, an essential element to optimal performance. To end, here is one last self test to determine whether you are light enough on your fingers, as enabled by good posture:

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.