May 9, 2021

RONALD EBRECHT

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Registration Practice in the Poulenc Organ Concerto

May 9, 2021

RONALD EBRECHT

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Registration Practice in the Poulenc Organ Concerto

Maurice Duruflé, who played organ at the premiere of the Poulenc Concerto.

Maurice Duruflé, who played organ at the premiere of the Poulenc Concerto.

Introduction

In this interview, Ronald Ebrecht, University Organist Emeritus at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, discusses the performance history of Francis Poulenc's Concerto for Organ, Timpani, and Strings in G Minor, and the influence of Maurice Duruflé on the registrations of the work in editions and historic recordings with Vox Humana Associate Editor Alcee Chriss III.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Professor Ebrecht, thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. As one of the foremost scholars on Maurice Duruflé’s organ music, how did you become specifically interested in the Poulenc Concerto?

My interest in registration practice began prior to my studying the music of Duruflé and Poulenc. My first explorations into a composer’s music relative to the first performance instrument was that of Herbert Howells. My master’s thesis at Yale was focused on what Howells’s music might have sounded like on the instrument that he knew at the time, as opposed to some of the commercial recordings we hear. In my later research into European registrations, I have tried to understand the balance between mixtures and reeds, and how that dichotomy changed in Europe over the course of the twentieth century. In my research on Duruflé, I’ve come to the conclusion that we shouldn’t abandon the warm embrace of the French Romantic sound world when realizing Duruflé’s registrations. These are the instruments Duruflé knew at the time of writing his organ compositions, and not the neoclassical organs of later decades. In fact, the 1892 Cavaillé-Coll organ on which the Poulenc Concerto was premiered existed as an expressly French Romantic instrument at the time of the premiere and changed at various stages before it became unplayable and was removed.

Any conversation about the Poulenc Concerto seems to necessitate a discussion of the Duruflés, since Maurice premiered the work and wrote the registrations that appeared in the first edition. What was your relationship with the Duruflés?

I first met them in October 1971. When I was between my Bachelor’s and Master’s degree, I was working on my French in preparation to meet them again in 1975. I arrived in Paris to see them but that was just after they were in a terrible car accident, and both of them were nearly killed. At that time, I communicated with Marie-Madeleine’s sister, Eliane Chevallier, who gave me an update on their condition.

In your latest book, Duruflé's Music Considered, you question the registrations in Duruflé’s organ scores published after 1950. What were Duruflé’s thoughts when you spoke with him about registration? I know that you reconstructed the original versions of the Duruflé organ works.

Many of the registrational changes in later Duruflé editions were published after the composer’s death. From the moment I first heard Duruflé’s music, I didn’t like the way that it sounded on French Romantic organs that had been modified to be more “baroque.” I talked with them constantly about this until Maurice died, and then until Marie-Madeleine died, and until Eliane died. Eventually, over time, they decided to endorse my study of the original versions of Duruflé’s organ works and my inquiry into what these pieces sounded like prior to the major aesthetic changes in French organ building around 1950.

How does the Neoclassical aesthetic fit into Duruflé’s sound world?

For the tenth anniversary of Maurice’s death, I gave a series of concerts performing his complete organ works. That’s when I really decided that I was tired of the known versions and of the known registrations. I began investigating the earliest versions of Duruflé’s works, and eventually I was able to get access to the entire trove of manuscripts held by Durand in their magnificent headquarters. Duruflé didn’t start changing registrations in his scores until the 1950s, specifically the registrations in his works for solo organ. One influence on him was undoubtedly Nadia Boulanger, who was pushing him toward Classical succinctness in his music; she’s the one who got him to remove a number of passages from his organ works. Nadia was an advocate of the Neoclassical school of composition, especially Jean Françaix. Aesthetically, the richness of Duruflé’s compositional style is not in any way related to Françaix’s or the Neoclassical instruments on which that music sounds best. My research argues that Boulanger wanted Duruflé's aesthetic to conform to a more classical model, which can be seen in the later editions of his organ works.

The premiere of Poulenc’s Concerto seems to have been tinged by some uncertainty and chaos. It seems that Poulenc got cold feet before the premiere, and that Duruflé was brought on to the project quite late.

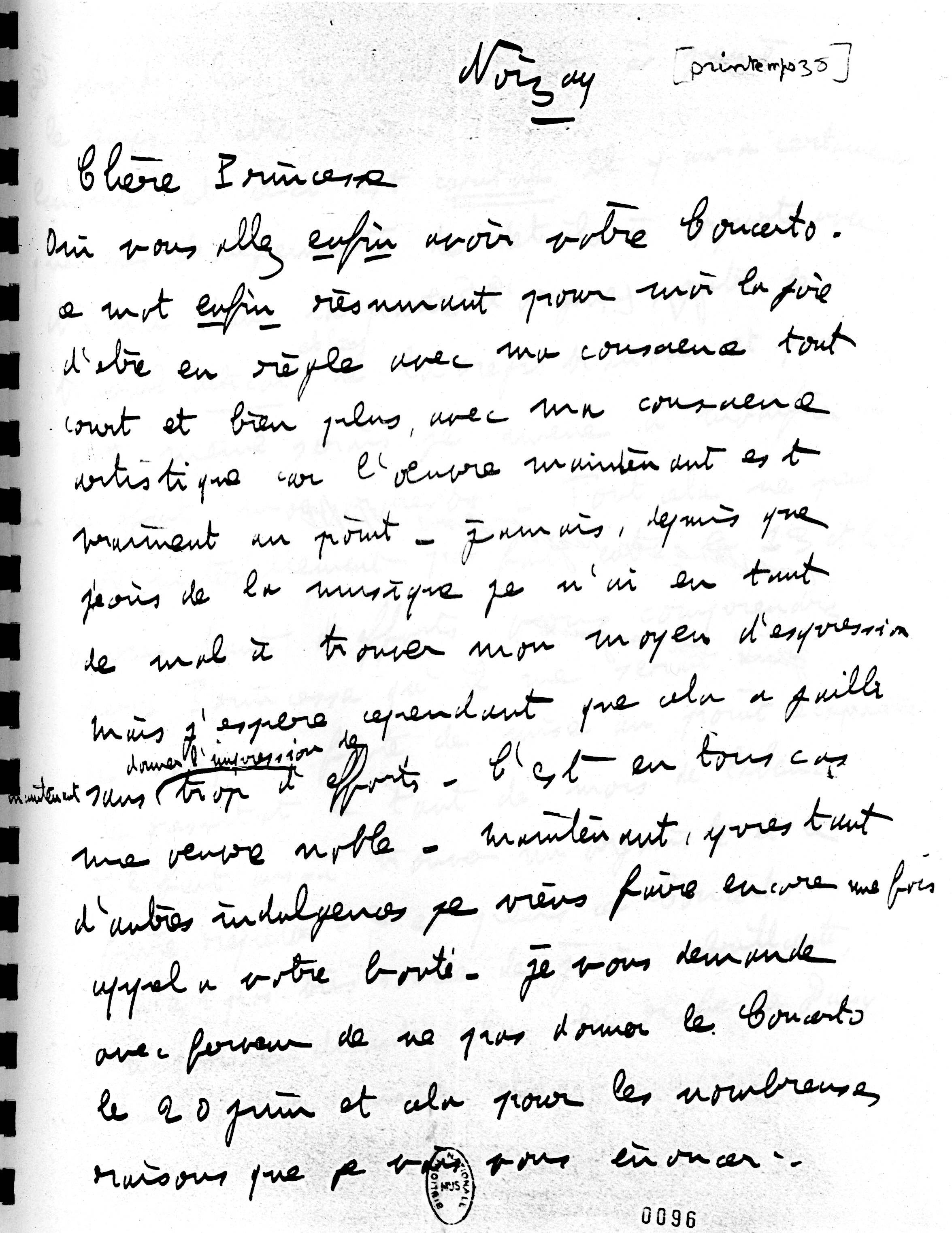

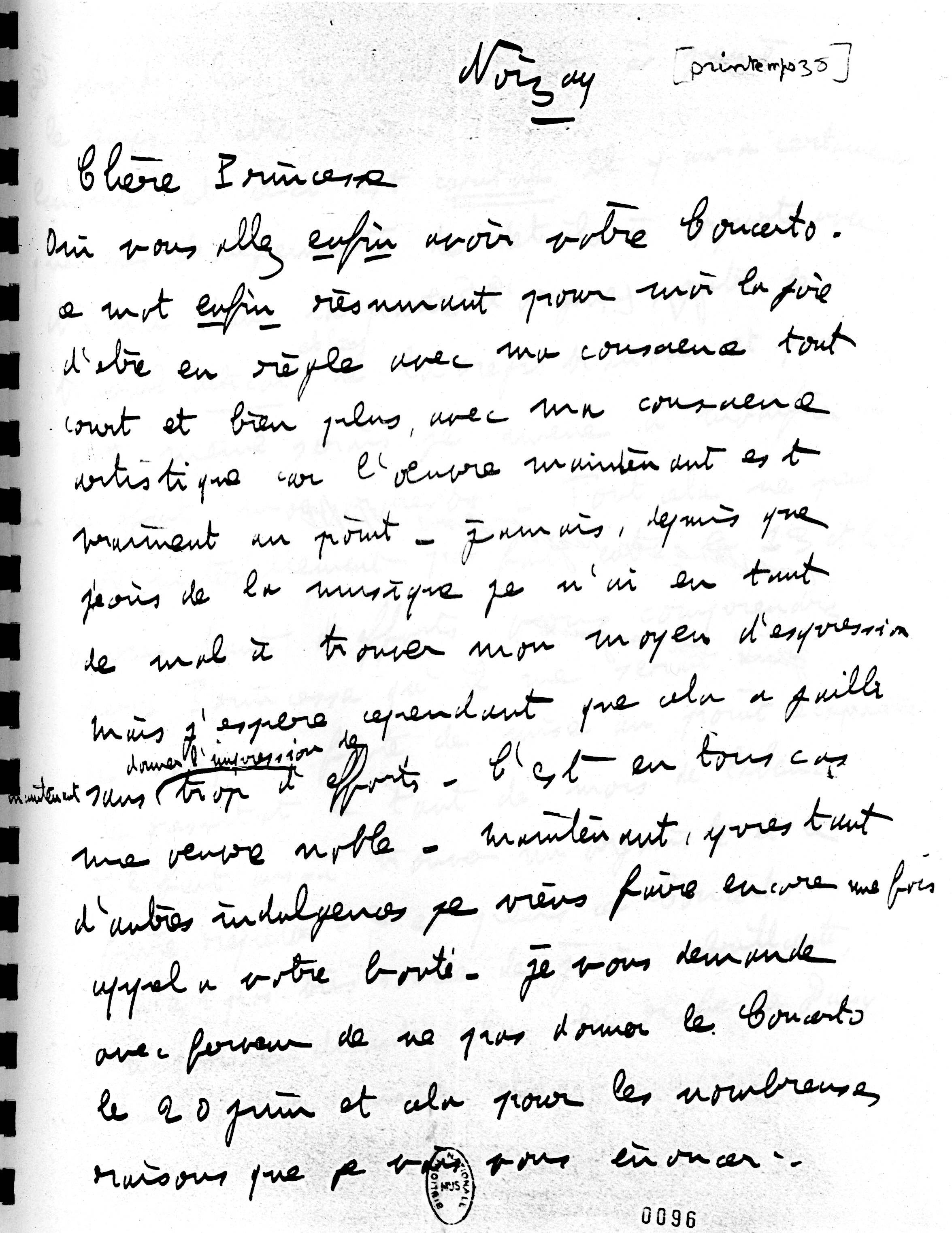

In an early correspondence, Poulenc said that he wanted the Concerto performed for the first time without a public audience. The original plan was to have the Princess Edmonde de Polignac, who commissioned the piece, play the concerto herself. At some point, the plan changed — we do know that Princess Polignac had already decided that she wasn't going to play the work by December 10, 1938. In a letter from Spring 1938, Poulenc says that they still needed to find an organist for the performance, even though the schedule for rehearsals was already set. Many people originally thought that Duruflé was a part of the inner circle for the conception of Poulenc’s Concerto, but a closer look at correspondence between Nadia, the Princess, and Poulenc shows that his involvement in the project was last minute, and in Poulenc’s letters we learn that he was working on registrations with Nadia Boulanger, not Duruflé.

Poulenc was fighting to have Nadia conduct the work and since the princess was unable to play it, an organist would need to be hired — in this case, Maurice Duruflé. After the premiere, Duruflé wrote a note to Nadia Boulanger on December 22, 1938, thanking her for getting the gig and commenting on how nice it was to play under her expert direction. In terms of history, all of the lore in the organ world has been that there was a close association between Duruflé and Poulenc during the composition of the Concerto, but we have documentation that shows that Poulenc didn’t really know who Duruflé was prior to the premiere.

In the Poulenc Concerto, we often see registration instructions that ask for soft, sometimes nearly inaudible combinations of stops. To me, it seems that some of the quieter registrations are so bare, that they really would not be heard in a large concert hall, for example in bar 24, where he asks for Flute 8’ and Dulciane 8'. How seriously can we take these registrations?

We really shouldn’t take Duruflé’s registrations markings too literally in the Poulenc Concerto. Firstly, there was not even a Dulciane 8’ on the organ of the premiere. I believe that performers should stick to the concept of a contrasting timbre between flute and string, but not sacrifice the organ’s balance for fidelity to a specific stop called for in the score.

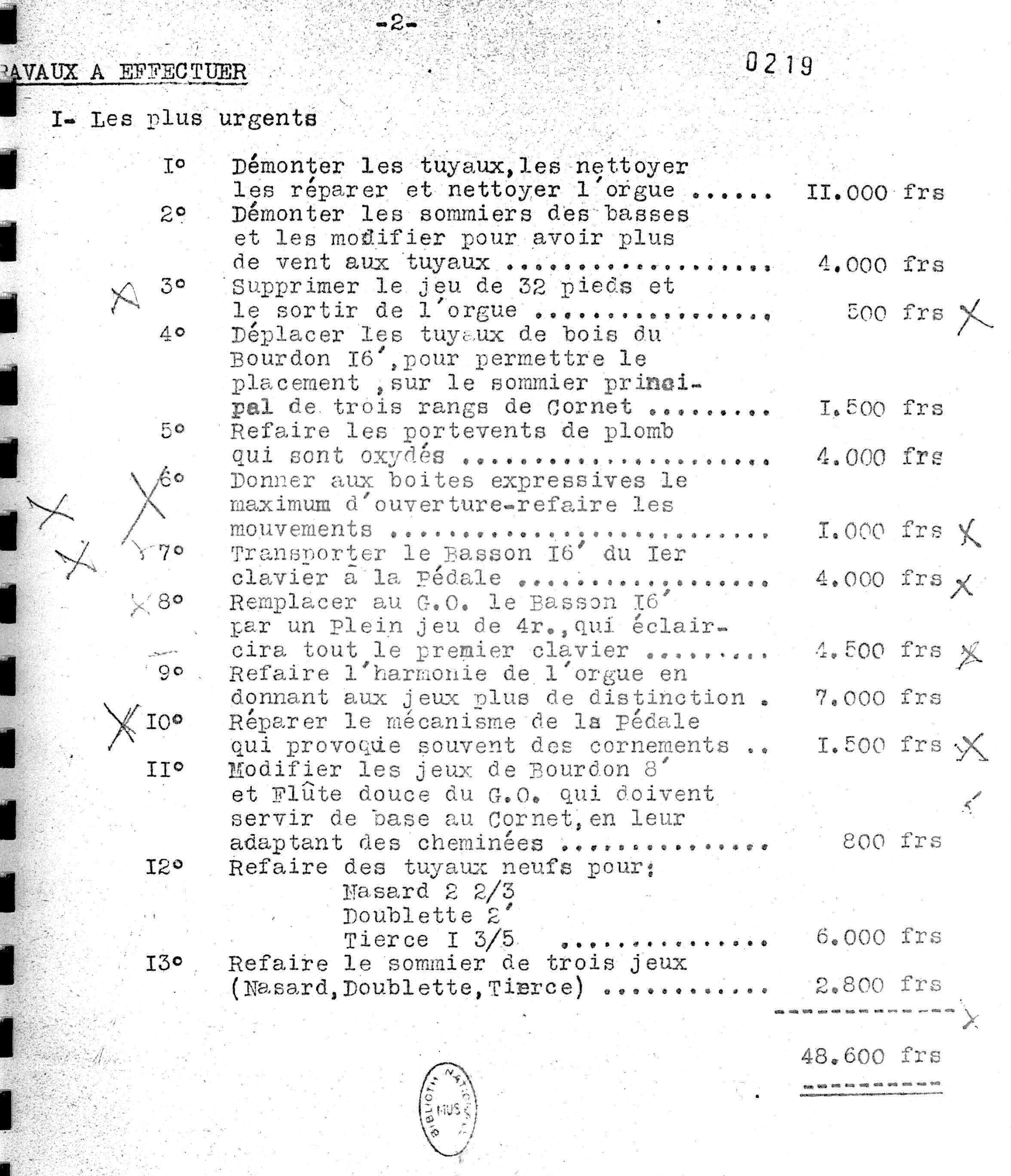

Secondly, you have to imagine if you were in the music room of the Princesse Edmond de Polignac, with 12 string players and an 18-stop Cavaillé-Coll organ with the following registration, reproduced from Jesse Eschbach Aristide Cavaillé-Coll: A Compendium of Known Stoplists:

| Grand-Orgue-Expressif Montre 8'Bourdon 8' Flute Harmonique 8' Prestant 4' Flute a Chimnee 4' Bassoon 16' Trompette 8' Clarion 4' |

Récit-Expressif Flute Harmonique 8' Viole de Gambe 8' Voix Céleste 8' Flute Octaviante 4' Octavin 2' Plein-Jeu III Basson et Hautbois 8' Clarinette 8' Pédale Soubasse 16' Flute 8' |

In these settings, yes, a Flute 8’ on the récit might balance with the orchestra. However, many church and concert hall organs have stops that are scaled such that they would simply be inaudible in live concerts or recordings. I think performers should take Poulenc’s dynamic markings more generally and aim for a good balance with the orchestra. I’ve seen performances where the audience is leaning over trying to hear what the organist is doing (and they make more noise in their seats than the quiet organ part does!).

One surprising aspect of the Poulenc Concerto is the seeming lack of registrations that would show off more of the reed colors of the organ. However, your recording from Woolsey Hall makes constant use of reed sonority — how did you come to this performance decision?

Well, one thing that made me feel free to use more solo reed color is from my direct correspondence with Madame Duruflé; I decided to thread the registrations similarly to things that she reported to me about what colors her husband liked. In particular, she said that her husband liked Frederick Swann’s use of American color stops (particularly the french horn) during the performance of the Requiem.

Maurice Duruflé discovered that the performance situation in America was nothing like that of France, and that this should guide American organists performing his works. He was excited by the varieties of color available on large American organs, and often found himself departing from his own registrations in the score, sometimes by necessity. Moreover, in one of my articles I discuss how Duruflé progressively changed the stop nomenclature for various solo lines in his pieces. He was much more interested in changing solo lines than with the chorus effects; we often see him revising solo stop markings to cycle between clarinet, flute, and cornet. An example of this in the Prelude and Fugue on the Name of ALAIN, Op. 7, where the solo lines that were originally assigned to the Flute Harmonique 8’ were given to the Cornet in later editions. In fact, there is not a single registration suggestion in the first edition of any of his organ works before 1950 that asks for a solo cornet. We also know that Cavaillé-Coll went around removing Cornets and putting in big strings — he wanted to have a symphonic oriented organ, not these kind of strange menageries of seventeenth and eighteenth century sounds that became popular again after the Second World War.

During my Woolsey Hall performance, when I wanted the organ to sound mysterious, I would use the Echo division at the other end of the hall. That gave me the sense of mystery without making it too soft. With 2,700 people in Woolsey Hall, you can get them squirming in their seats with the Echo division. You can’t just pull the Dulciane 8’ on the choir — nobody will hear that over the noise of the audience!

Poulenc is so often put into the camp of “Neoclassical” composers, which perhaps explains why organists tend to lean toward brighter, mixture-dominated registrations in the performance of the Poulenc Concerto. In that piece, I notice Duruflé often asks for the mixtures prior to the chorus reeds, which is unlike most of his organ works. Can you also tell us why people sanctify the 1961 Duruflé recording as the gold standard for the piece?

I have studied that Duruflé recording and I know the instrument of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont intimately in all of its incarnations over almost a century. I think that this 1961 recording was his chance to show off his newly completed organ at Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. And mind you, he could make things any way he wanted. So he could use the Dulciane 8’, and the sound engineers could edit the sound to focus on that section of the room. I think that recording was Duruflé’s chance to make a statement about what he’d done with his instrument, more than a “final word” about how to register the Concerto.

In terms of organ building aesthetics, the 1930s are right on the brink of the shift toward more neoclassical registrations for the organ. How might that determine our approach to registration in the piece?

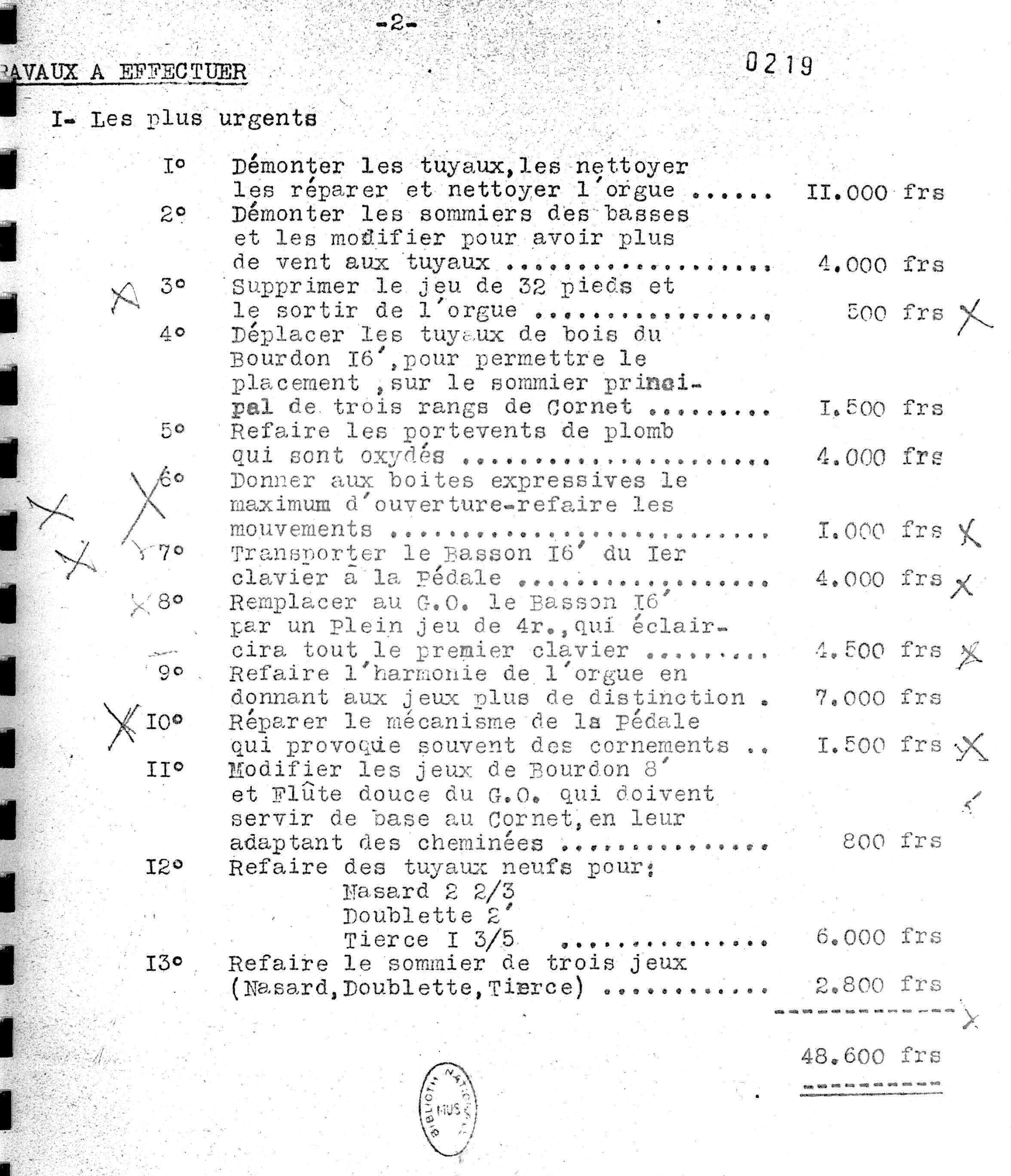

Nadia Boulanger had a lot of control over the premiere of the Poulenc Concerto, and she was an early advocate of adopting the neoclassical aesthetic. As I mentioned in my article for The Diapason (available here), Nadia wanted to alter Princess Polignac’s Cavaillé-Coll organ to be “brighter” in 1933. She successfully added a mixture stop to the Great Division, but was prohibited from adding a Cornet. As you can see from the Neoclassical changes that Nadia suggested to the organ in 1933, she was ahead of her time in wanting to substitute foundational tone with higher pitched mixtures and mutations.

Moreover, it should give the performer freedom to know that Duruflé did not write either set of registrations for the initial performance. We do know however, that the organ for the premiere was more dominated by foundations and reed stops than by bright mixtures.

Mixture-dominated registration in this work often does not blend with the orchestra. When there are only strings and timpani, you won’t be able to hear them well over screaming mixtures. If the work were scored for brass with a full orchestra of 110 players, it would be more appropriate to use these louder mixtures, but in the case of the chamber orchestra of 12–15 string players as were at the premiere, it was physically impossible on the organ at that time.

Do you have a final word about how to approach the performance of the Poulenc Concerto?

Pianists play concertos all the time, various instrumentalists likewise. They have an innate sense and a long performance practice history of knowing what the purpose of a concerto is: to dialogue with the orchestra, and not to underwhelm or overwhelm it. Organists don’t get much opportunity to perform concertos, and when they finally get one, they often seem to think of it as “their chance,” and not as a participatory event. In my recording at Woolsey Hall, you can hear that I hardly ever go anywhere near a tutti sonority, even though I had 90 instrumentalists on the stage. The effects that the organ achieves in most major orchestral works are to underpin the orchestra and add color, not to run the show. Duruflé himself played in orchestras as a keyboardist and understood the collaborative experience of working with an ensemble.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.