October 22, 2017

STEPHEN BUZARD

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

On Big Shoulders: Learning Sowerby at St. James Cathedral, Chicago

October 22, 2017

STEPHEN BUZARD

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

On Big Shoulders: Learning Sowerby at St. James Cathedral, Chicago

Introduction

Stephen Buzard, Director of Music of St. James Cathedral in Chicago, describes working in the same space as the notable twentieth-century American composer Leo Sowerby, and provides previously unpublished photographs of "The Dean of American Church Music."

––––––––––––––––––––––––

All organists share the experience of spending a late evening in a darkened church, toiling away to master a new piece of repertoire. It is during these hours of solitude that we begin to get inside a composer’s head and transform his or her work from an enigmatic arrangement of ink on a page into living expression. My recent practicing has felt especially personal and elucidating because my current projects were written in precisely the same location where I am learning them.

When I accepted the call to become Director of Music at St. James Episcopal Cathedral in Chicago one year ago, I was well-aware of (and perhaps a little intimidated by) Leo Sowerby’s towering legacy as organist-choirmaster there from 1927–1962. Truth be told, I played almost none of his music and had only a surface-deep appreciation for the breadth of his output. Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of Sowerby’s death, and I have decided to begin tackling his repertoire in earnest. As I tell colleagues of my plans to do a Sowerby recital tour and recording in 2018, their responses generally fall into one of two camps:

1. “I love Sowerby! He is the great American organ composer, etc.” or

2. "Why???"

I hope that my experience working at the same church where Sowerby spent most of his composing years can translate into a deeper understanding of his music, and that my performances may encourage a deeper appreciation of America’s most significant composer for the organ.

Although Sowerby is remembered primarily as composing music for choir and organ, he wrote prolifically for virtually every medium except opera. In his youth, he won the Rome Prize in composition, became a de facto composer-in-residence for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and joined the faculty of the American Conservatory of Music at the age of 29. During this early phase in his career, Sowerby held various church jobs but probably never dreamt that he would eventually be dubbed the “Dean of American Church Music.” He became Organist and Choirmaster at St. James only through a bizarre series of events. When John W. Norton, Organist and Choirmaster from 1919–1925, mysteriously disappeared, Sowerby was called to fill in for a brief stint. The next titular, Percy D. DeCoster, was (by all reports) such an unmitigated disaster that he held the post only 18 months. Sowerby was brought back in 1927, this time staying until 1962.

The young Sowerby was well-regarded as an organist and composer but seems to have had little sensitivity or training in the Episcopal way of doing things. According to a review in the April 1928 issue of The American Organist, Sowerby programed “Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones” with its prominent “Alleluias” for a Lenten service. (The abomination of reviewing acts of worship in a trade journal warrants a tirade of its own…). The Rector promptly encouraged him to spend the summer in England where he could absorb the ins and outs of the Anglican tradition. In overcoming this learning curve, Sowerby fell in love with the Episcopal Church and was confirmed at St. James soon thereafter. The liturgy at St. James not only gave Sowerby a new medium for composition but new inspiration as well. He wrote dozens of canticles, anthems, and cantatas for the St. James choir. His setting of the Passion Forsaken of Man was performed annually by choirs across the country in the 1930s and ‘40s. His monumental cantata Canticle of the Sun went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1946. Had it not been for St. James, Sowerby would not likely have followed this sacred trajectory that launched his career.

Through his compositions and teaching, Sowerby’s harmonic language has permeated the psyche of American organists. His colorful chordal palette sounds like jazzy genuflecting, always reverent but perhaps a little naughty at times. As I encounter some of these harmonic turns in Sowerby’s music, my first reaction is “that sounds like Gerre Hancock” — when in fact, it is the other way around!

Sowerby’s playfulness, complexity, and daring has since become a building block of the modern Episcopal style of improvisation. Hancock was a mentor to my mentors, and thus the ghost of Sowerby is already present in my improvisational idiom.

The walls of St. James Cathedral are surprisingly sound permeable, and as I practice some of Sowerby’s contrapuntally densest writing, the busyness of the music seems to play off the noises of the street. I can’t help but wonder if Chicago’s 1920s sonic cityscape is subliminally buried inside Sowerby’s music — bustling carriages, the clang of trolley cars, puttering Model Ts in a thinly-veiled, almost out-of-control chaos. The improvisatory spinning out of his melodic development in a work like Air with Variations was clearly inspired by the spawn of the Jazz Age, the illicit love child of César Franck and the seedy stuff played in smoky speakeasies operated by Al Capone.

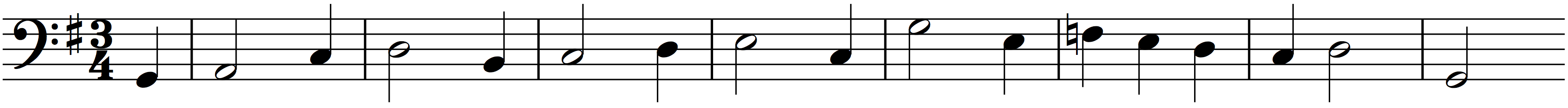

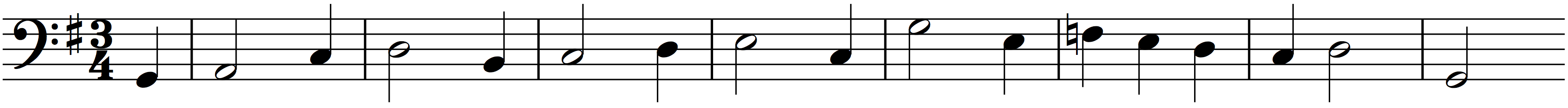

But Chicago of the 1920s and '30s was about more than Prohibition and automobiles. The “City of Big Shoulders” stood for optimism and the pioneering spirit. Boosterism was big, and the city prided itself on a slew of civic accomplishments. Yet there has always been a self-consciousness to “Second City” Chicago, as though it is constantly having to prove its parity with the coastal metropoles. I hear this existential conflict in Sowerby’s writing as well, and yet a thoroughly Midwestern optimism and confidence underpins his music. For example, whereas passacaglia themes typically follow a downward shape (e.g. Bach, Buxtehude, Willan), Sowerby’s passacaglia from the Symphony in G Major points ever upward:

At the same time, his music’s complexity and ingenuity can make it feel overwrought, as though Sowerby is constantly trying to prove his cleverness. One can certainly never dispute the common critique that his ideas have not been fully worked out, or that he errs on the side of simplicity!

Organists and composers for the organ are like wine, in that the place that nurtures them determines their flavor. The rooms and instruments we routinely play shape us in ways we never realize. St. James Cathedral’s acoustics are basically as Sowerby would have known, and though it is not a reverberant room, the sound is very clear. Sowerby’s hallmark density of texture may not have been successful in a European cathedral, but it is very satisfying here. The 1920s Austin over which Sowerby presided is largely gone, but by all accounts, it was quite a milquetoast organ. The current organ sits atop the old action, and I can attest to its sluggishness. As a result, Sowerby’s music does not rely on the beauty of a single timbre but demands a kaleidoscopic approach to registration. The organ’s lethargic response and woofy onset may be one reason why he marked his scores with such attention to articulation; he had to be especially deliberate in attacks and releases to make the organ sing. It is rare to find any notes in a Sowerby score unadorned by a slur, staccato, tenuto, accent, or other marking or a combination thereof.

His obsessive approach to markings did not stop just with his own publications. In our choral library, we still have scores from his era, and they are an interesting window into his personality and his aesthetic. Every breath, dynamic, etc. was marked in each copy in blue colored pencil in the same hand (presumably that of his music librarian). While the thoroughness is commendable, one cannot help but suppose it sacrificed spontaneity.

I offer these thoughts on Leo Sowerby as I continue to discover his music at St. James. I hope that these ideas may encourage others to study this oft-overlooked composer and find new ways in which we can appreciate his music. Regrettably, there is virtually no biographical material available on this great composer. I have referred to a 1957 Master’s Thesis by Ronald Huntington at the University of Southern California, to my knowledge the only such source available. Hopefully an enterprising scholar will take on a biography of Sowerby.

I would also like to acknowledge the help of Tom Sheehan, who helped me expand on the ideas presented in this article.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Vox Humana Editorial Board extends our warmest thanks to the Leo Sowerby Papers at the Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center for digitizing three photographs featured in this article, and to the Leo Sowerby Foundation (especially Francis Crociata) for digitizing the photographs in this article and for their kind permission to reproduce them here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.