February 11, 2018

FRANCK BESINGRAND

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Louis Vierne: A Legendary Figure

February 11, 2018

FRANCK BESINGRAND

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Louis Vierne: A Legendary Figure

Over the decades, much has been said or written about Louis Vierne, sometimes with biases that attempt to maintain the image of a legendary figure, making him into a victim of fate. Admittedly, Vierne’s destiny was difficult — even cruel! Beyond the differences of aesthetic viewpoints, it is certain that the man and his music cannot leave anyone only indifferent. Even those who find an excess of pathos, chromaticism, formalism, or too bleak an atmosphere in his music can still recognize the singularity of Vierne’s message, one brought forth through his sincerity and authenticity.

The singular destiny of Louis Vierne is conveyed by his music, often dark and feverish, but equally — one forgets! — luminous and exuberant with strength (both exemplified in his Messe Solennelle). His art cannot dissociate itself from the many hardships in his life: quasi-blindness, professional setbacks and betrayals, frequent emotional breakdowns, cruel bereavements, on top of a hyper-sensitivity; Vierne even qualified himself as sickly, a state which tormented him. Others were aware of this throughout Vierne’s life, too; Léonce de Saint-Martin (Vierne’s successor at Notre Dame) recalled, “the shadow from which the man came was never brightened by a landscape of lights in his life.”

One of his qualities resided in the strength of his nature, with a bravery to endure to the end; Joseph Bonnet, one of his students, further testified to this in the journal Monde musical (1937), “In all his misfortunes, he confronted a strength of soul and an invincible energy.”

The man himself is fascinating at first glance: always described as intelligent, scholarly, and open-minded in many subjects (Maurice Duruflé once wrote that “[Vierne’s] conversation was dazzling”). Equally remarkable as a pedagogue, Vierne was named a Master éducateur by Henri Doyen, who summarized the main components of Vierne's teaching: rhythmic crispness, clarity and precision in registration, sense of phrasing and its architecture, and rigorous legato.

If his retorts, amusing and sometimes fierce, testify to the breadth of his point of view and to his sometimes-caustic wit (which can be seen in his scherzos), his sensitivity, the fierce independence of his spirit, and leaps of humor (which, according to his student Henri Gagnebin, “one must never take literally”), remained dominant traits of his nature. Additionally, the instability of his character, which could manifest in moments of weakness, sometimes rendered him more easily manipulated.

His Artistic Ideal

Despite this, Louis Vierne’s artistic ideal remained elevated without concession, and he never diverted from his artistic trajectory out of loyalty to his masters and his models, remarking “we must continue to advance in the path that was traced for us.” But, especially after 1920, he valued a kind of isolation from the artistic sphere, mistrusting those who loudly and strongly heralded tradition and the models of the past in an age when composers searched to free themselves from well-established musical forms and from an overly conventional harmonic language (if not for an entirely clean slate). Vierne was not completely unmoved by the changes of musical modernism in the beginning of the twentieth century; there, he found material for his creative development, seen particularly in the Sixth Symphony. He rebelled against angular modernism and distrusted the effects of fashion that he considered to be fleeting. He preferred to coordinate instead of scatter, and anxiously watched the frantic surges and this frivolity in the antipodes of his aspirations.

As of 1930, weakened by his taxing illness, he withdrew from public life, no longer finding the strength to battle and create; he wrote to his student, Canon Henri Doyen: “I need a particular kind of grace to accomplish my task despite the insidious external solicitations. Alone, I am too weak and too spent.”

June 2, 1937

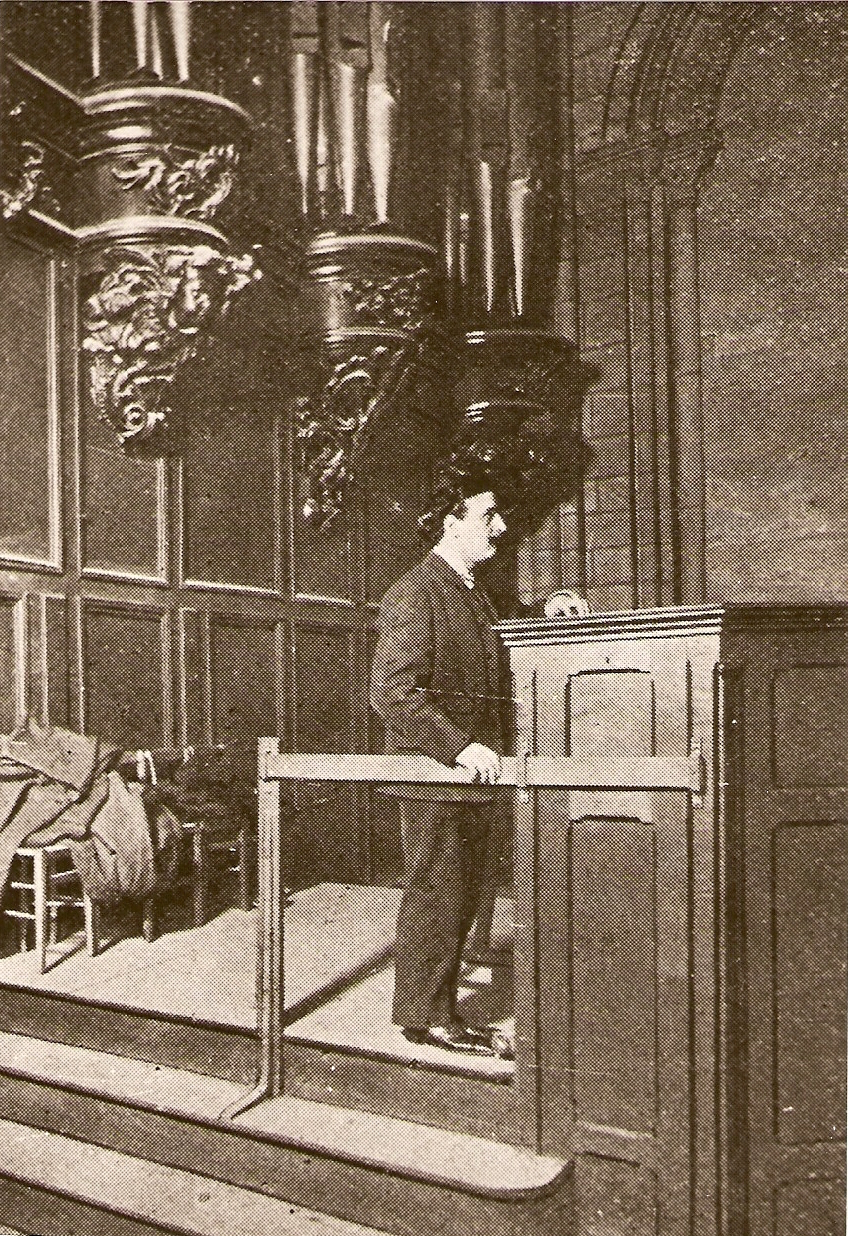

Louis Vierne’s last concert at Notre Dame Cathedral was, according to a testimony from Madeleine Richepin, already ill-fated; she described that he gave every ounce of his strength, and felt that he would die. All his students and friends had come to honor him, but one, Norbert Duforcq, later recounted, “We were painfully taken aback by his emaciated appearance, with its unusual pallor and tense lines.”

Jean Fellot, former student and friend of Vierne, found himself at his former teacher’s side with Maurice Duruflé. In a letter dated June 11, 1937 (addressed to Jean Bouvard, kindly shared by Michel Bouvard), Fellot emotionally shared the final moments of his teacher and his weakness at the end of the Triptyque: “The master sagged. His foot sank into the note of a pedal, making a sound like a distress call. One first thought that he had fainted: M. and Mme. Mallet tried to revive him before we transported him out of the balcony, and it is in my arms that he sighed his last.” It was exactly 9:30 P.M.

The events hastened: Vierne was transported to the Hôtel-Dieu, just beside Notre Dame. According to Fellot, “All the organists who came to Hôtel-Dieu withdrew quietly, their eyes filled with tears.” Duruflé gives further details: “Nobody will ever forget this tragic night — the bewilderment that seized all those who attended.”

As Louis Vierne was the titular organist of Notre Dame Cathedral, his death and the subsequent need for a successor unleashed an incredible, vast controversy in the religious and musical community, resulting in a petition from Notre Dame’s Amies de l’Orgue requesting that the cathedral hold a competition for the successor of Louis Vierne. The clergy was inflexible, though, and Léonce de Saint-Martin, already working there as a substitute, succeeded Vierne. Joseph Bonnet, certainly not alone in his thoughts, concluded, “Thus intrigue triumphs among the religious milieus, even more than in those contaminated with politics.”

Influence of His Organ Works

The organ works of Louis Vierne are deeply rooted into the repertoire of organists worldwide. This music has never known a true decline, as evidenced by concert programs and numerous European, Canadian, and American recordings of the last 50 years. These works remain deeply linked to the Cavaillé-Coll organ of Notre Dame, which is so connected to his aesthetic as organist — an aesthetic that was, essentially, symphonic. Vierne commented, “I discerned that the grand decorative style was the only one that could suit a vessel like that of Notre Dame.” He also knew how to profit from his experiences with English and especially American organs, as evidenced by his triumphant tour in 1927 and certain movements from the Pièces de Fantaisie, which are sometimes exceedingly innovative in their writing and registrations.

True to his place as inheritor of the lineage of his teachers César Franck and Charles-Marie Widor, Vierne knew how to deftly combine the technical and expressive possibilities of the symphonic organ with his brilliant musical ideas, contributing to the dramatization of the organ symphony. This energy is one of the key aspects of his style, which one sees in the myriad of finals of the Symphonies and in the extraordinary magic of Feux follets or Naïades, or the Scherzo of the Sixth Symphony.

Vierne had no equal for perpetual movement driving towards sonorous exhilaration. The engine-like quality, constantly renewed and re-energized, that he releases in these allegros is impressive. Thus the Final of the First Symphony, famous and exhilarating, gives a dominant role to the principal motif, with its incisive rhythm circulating from voice to voice and dashing towards the coda in a whirl.

Colorist and orchestrator, Vierne individualized the themes with a stereotyped registration, as shown in first motif of the Intermezzo of the Third Symphony, which is a little strange with its Spanish dance rhythms. Vierne displayed the most originality in registration in his scherzos: the two sonorous plans of the Scherzo of the Sixth Symphony, which use the mutation stops, contrasts beautifully with the bold sonorities many of the other movements. There are numerous other examples in which one can find similarities between these organ works and his pieces for orchestra, which are still little-known and much richer than they might appear (I would say that they even challenge the old idea that ‘an organist can only write for the orchestra as if it were an organ’ — see Praxinoé, Psyché, Eros, and Poème).

To Love His Music?

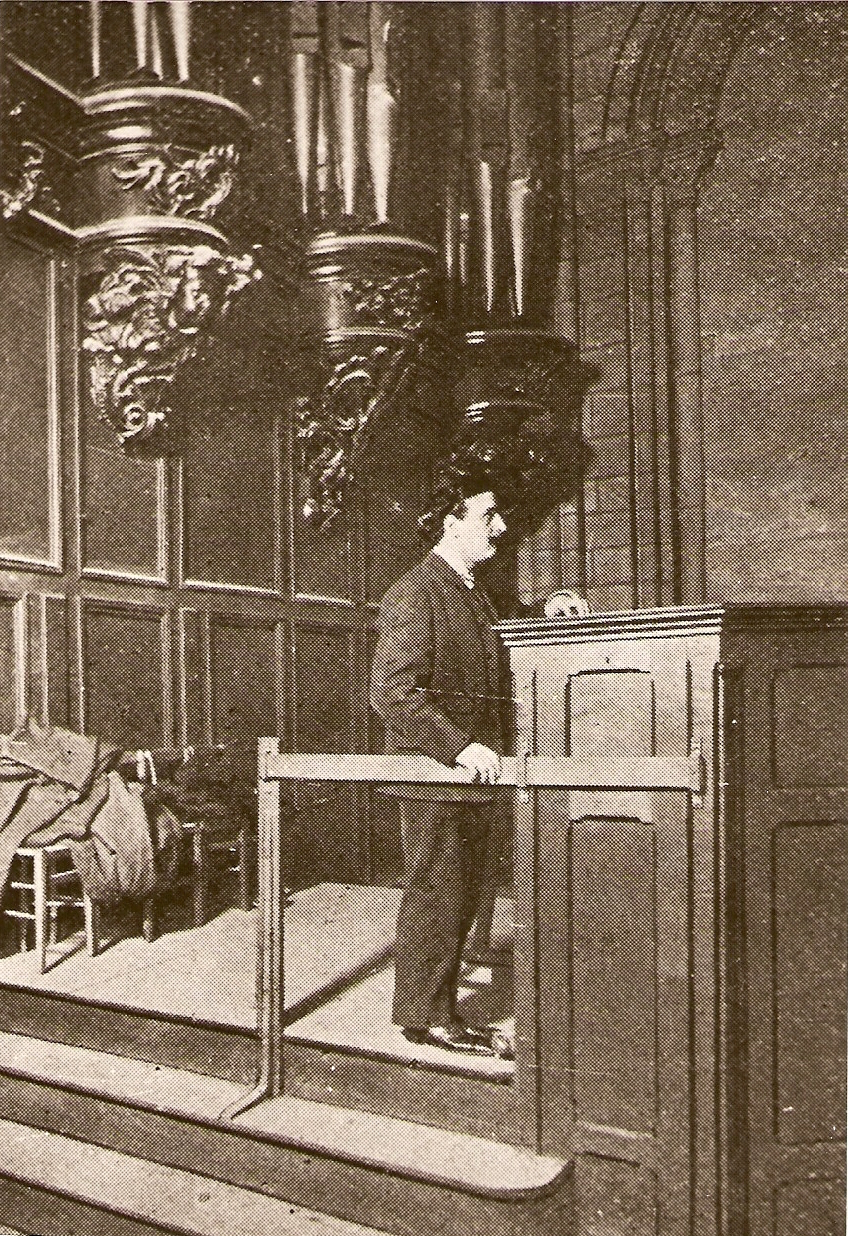

To love the music of Louis Vierne is to know to find him at Notre Dame, even looking past his legendary death during his final concert. “Vierne was so identified in this grandiose context, and so totally involved there that he became the soul of the Cathedral,” Maurice Duruflé wrote. At some point, Vierne became even more of a god-like figure. Duruflé wrote of his playing, “I knew the most complete feelings of domination, of total possession,” highly convincing in his mission and in his aura on the anonymous crowd of celebrity personalities (Clémenceau, Joffre, Barres, Huysmans, Rodin, Renoir...). Duruflé explains: “One must know how to give rhythm to the emotion of this sweeping crowd below.”

Vierne, organist of the Cathedral! Who else was so completely within the spirit of his teachers, on the level of his form, so much so that he could even alienate himself (especially in the 1930s) from the truly innovative works of his contemporaries Messiaen and Alain? One cannot deny that one of the great forces of Vierne’s organ art and general aesthetic resides in his mastery of clear polyphony and ability to deftly weave together a juxtaposition of musical ideas using a subtle game of oppositions of sonorous plans (following the example of Widor). Norbert Duforcq recalls that Vierne said “It is about giving the work an iron. Structure.” And Vierne provides yet another explanation: “I searched for the sharpness of ideas, the clarity of plans, the solidity of the construction and the coloration of large keys.”

All of Louis Vierne is held in these few lines, even if this portrait needs more development. It is up to each of us to paint this portrait with enthusiasm for his music, which is constantly present in our hearts.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Born in Bordeaux,

He has won several prizes in organ competitions, including the UFAM Honorary prize and Composition prize (notably in 2010 in the Swiss competition Lonfat-Stalder for his work on Couleurs d’Etoiles). His compositions have been published by Combre and Rubin. As a musicologist, he has studied the music of Jean Langlais, the repertoire and the musical language of the French Classical organ, and the relationship between the organ and the orchestra during the nineteenth century. He has also published a study on Louis Vierne in 2011 with bleu nuit éditeur, Paris. He is currently preparing a book about Henri Duparc.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.