September 30, 2018

MICHAŁ SZOSTAK

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Largest Pipe Organs in the World

September 30, 2018

MICHAŁ SZOSTAK

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Largest Pipe Organs in the World

The console of the 1932 Midmer-Losh organ at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the largest organ in the world.

The console of the 1932 Midmer-Losh organ at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the largest organ in the world.

Introduction

Considering which organs are the largest leads to a major issue of their comparison: objectively, what makes one organ larger than another? The existing literature on the subject and the various classifications present the rankings of selected instruments on the basis of various criteria are often inaccurate, and there is no comprehensive approach to this subject in literature of the subject.

There are many methods of classifying organs in terms of size, and each has some degree of imperfection, because each instrument is unique in its own way. The following is a summary of the most common criteria for classification of organs in terms of size:

| Criterion | Possibilities | Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Number of stops | Real stops, combined stops, extensions, transmissions | Many stops do not have the same number of pipes per note (i.e. Cello 8' versus Mixtur V) |

| Number of pipes. | Playable pipes, muted/dummy pipes (in façade) | Difficulty verifying the number of pipes |

| Number of register switches | Stop switches, combined stop switches, coupler switches, combinations | The number of switches increases the sound capabilities but does not necessarily affect the size of the instrument |

| Number of ranks of pipes | Same issue as number of stops | Optimal criterion when specifiying additional issues |

The most common criterion for classification of organs in terms of size is the number of stops. However, stops are extremely diverse in terms of material and construction (wood/metal, labial/reed), the amount of material used (a 2' flue stop versus the same kinds of pipes at 16ʹ), and the degree of complexity (one rank versus many ranks). In addition, some organs have stops in which each key plays only one pipe of the scale; some use combined voices — using pipes of other real stops to create an imitation (e.g. an acoustic stop Subcontrabass 32' achieved with a combination of real stops Subbass 16' + Quintbass 10 2/3'); extensions — adding a missing octave (or more or less) to the top or bottom of a rank of pipes to give a higher or lower pitch for a specific interval (e.g. adding an additional low octave to an 8’ principal could result in a 16’ principal stop in electric action instruments); and transmission — voices that use a single row of pipes to obtain a given sound in two or more sections (one rank of pipes could result in a 4’ principal and a 3’ principal).

The second criterion for comparing size is the number of pipes. This is problematic because practically, verifying the actual number of pipes in each instrument can be nearly impossible (some instruments have tens of thousands of individual pipes). In addition (though to a much lesser extent), there is the issue of the distinction of playing pipes from muted/dummy pipes (those placed in organ façades only for aesthetic reasons).

The third criterion for organ classification in terms of size can be the number of switches (stop knobs, buttons, rocking tablets, etc.) in the organ console/keydesk. This criterion is the least accurate, because the switches refer to real registers, combined registers, fixed and free combinations, additional equipment, and many other variants. Certainly the number of switches increases the musical capabilities of the instrument, but it does not necessarily indicate its actual physical size.

The last criterion could be the number of ranks of pipes playing in terms of real stops. This criterion is sufficiently precise, and so along with the additional assumptions discussed, this will be the basis for my analysis.

Criteria for this Study

Specifically, the criterion for classifying instruments for this study is "the number of rows of pipes and additional equipment managed from a single console.” The names of “rank” and “choir” of pipes are the same and will be used interchangeably.

All single row stops (each type: flue and reeds) will be counted, and the number of rows in the multi‑rank stops with a fixed number of choirs (e.g. a Mixture V counts as 5, Sesquialtera II as 2, etc.). In stops with varying number of ranks (e.g. Cymbel III– IV), the mathematical mean of the smallest and greatest number of ranks will be calculated. All manual and pedal stops will be treated equally; because of the natural features of the organ (different scales and number of pipes in a stop), each of these stops plays an important role in the full range of adequate keyboard (manual or pedal).

In addition to organ stops (particularly large and popular theatrical instruments in the United States), there is also equipment such as “toy stops” that significantly affects the size of the instruments. For our purposes, I will only count devices that can perform various melodic sequences (according to the will of the player, not permanently programmed) with a minimum scale of two octaves with diatonic and chromatic sounds (e.g. tubular bells, gongs, bells, harps, pianos, etc.). How important this type of equipment is from a musical point of view and for the purposes of this study may be the fact that, for example, in the Wanamaker Store organ in Philadelphia, one entire division consists only of such devices.

For the purposes of this classification, additional accessories with unchanging and "programmed" sound levels, which can only be switched on and off (e.g. Zimbelstern, timpani (two pipes), nightingale/cuckoos, etc.) will not be included.

The last criterion is that all pipes and additional equipment must be operated from one console, even if arranged throughout the interior of a building. For example, in the Cathedral Basilica in Gdańsk‑Oliwa, Poland, there are a Main Organ, Altar Organ and Positive Organ. Because all these instruments/sections can be operated from one console, I will treat them as a single instrument. Alternatively, instruments in the basilica of Leżajsk, Poland (the Main Organ, The Right Nave Organ, the Left Nave Organ), although located in the same loft, are not managed by one console, so I will treat them as three separate instruments.

Calculated real stops and rows in individual instruments (sections) will be summed up as they can be combined in a collective console. Final sums of real stops and rows of pipes, if given a fractional result, will be rounded to full (0.01–0.49 down, 0.5–0.99 up). An example of the calculations made on the basis of the East Organ and the West Positive Organ of the Basilica in Licheń Stary, Poland is presented here:

| Stops | Name | Ranks | Stops | Name | Ranks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gedeckt 8' | 1 | 1 | Voce umana 8' | 2 | |

| 1 | Diapason 8' | 1 | 1 | Gamba 8' | 1 | |

| 1 | Prestant 4' | 1 | 1 | Aeolina 8' | 1 | |

| 1 | Oktawa 2' | 1 | 1 | Vox coelestis 8' | 1 | |

| 1 | Cymbel III–IV | (3+4)/2=3.5 | 1 | Principal 4' | 1 | |

| 1 | +Tuba Magna 16' | 1 | 1 | Fugara 4' | 1 | |

| 1 | +Tuba mirabilis 8' | 1 | 1 | Harm. Aeth. III | 3 | |

| 1 | +Clairon 4' | 1 | 0 | Nachtigall | 0 | |

| 8 | EAST ORGAN | 1 | 7 | WEST POSITIVE ORGAN | 10 |

The classification criterion selected for this study are complemented by several additional assumptions. First, the transmitted stops will be counted only once. Stops that are not full-compass will be counted in proportion to five octaves of keys that exist in the manual (e.g. an Unda maris 8', whose lowest note is C3 will be counted as 0.8 of row) The enlargement of the stop will be calculated proportionally — for instance, if in the manual a Bourdon 16’ stop is enlarged by 12 pipes to achieve another stop labelled as Bourdon 8', those pipes that are exclusive to the Bourdon 8’ will be counted as 0.2). In the pedal stops, the average compass is considered to be 2.5 octaves; thus, if a Subbass 16' has an extension of 12 pipes to achieve a Gedackt 8' stop, the latter will be counted as 0.4. Stops with electronic audio sources will not be included. Finally, even instruments that are not fully playable will be considered according to what parts are extant, even if they do not function properly.

Course of the Research

I compiled three groups of organ rankings: for Poland, for Europe and the rest of the world. The candidates for largest organ come from various organizations and institutions that have catalogued large numbers of instruments (including The Organ Historical Society, the "Sacred Classics” radio station from Florida, the Spanish "International Organ Foundation", and private persons (e.g. Eberhard Geier and Martin Döring). Also helpful were websites that allow users to sort their own databases in terms of the number of stops or the number of manuals in instruments. Identification of each instrument was as follows: continent, country, city, object, type of object (sacred/secular), organ builder, date of construction. As the content of subsequent rankings was added, the list of the top 20–30 candidates for largest instrument emerged from each group. From there, I strove to compile a reliable specification of each instrument; as far as possible, I sought to obtain a specification of each instrument from at least two independent sources. With the exact disposition of each instrument (including stop name, pitch level, 16’, 8’..., sound range or number of pipes, number of rows, transmissions, extensions, etc.), I calculated the numbers of real stops and number of pipe rows and accessories as described in above methodology. Then, the results were entered into the main Excel spreadsheet. With the help of tools for filtering data in Excel spreadsheets prepared for the following 30 largest organs of USA, Europe and the world, it was possible to present the following rankings.

Rankings

Having a well-defined criterion for evaluating the size of the instrument, one can build endless numbers of comparative rankings of the pipe organs.

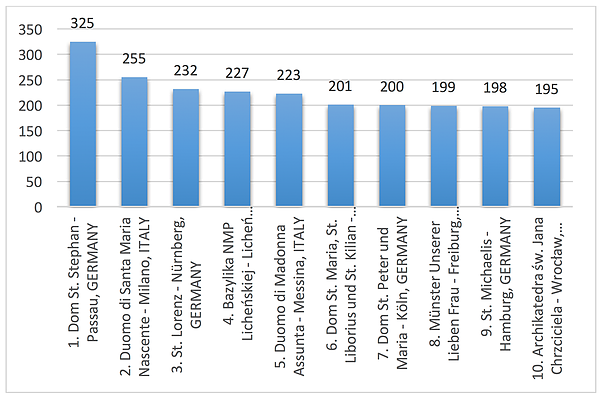

The Largest Organs in the United States

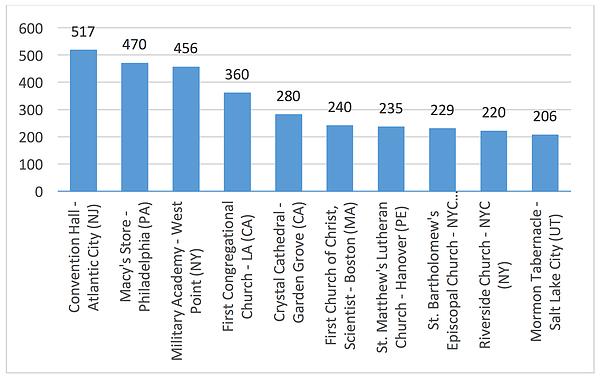

According to this methodology, the ten largest organs in the USA are as follows:

| No | City | Place | Builder | Manuals | Stops | Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlantic City, NJ | Boardwalk Hall | Midmer-Losh | 7 | 381 | 517 |

| 2 | Philadelphia, PA | Wanamaker Store | Los Angels Organ Col, Fleming & Till, Quimby | 6 | 395 | 470 |

| 3 | West Point, NY | Cadet Chapel | Moller, VanSeters, Ferguson, Chapman | 4 | 382 | 456 |

| 4 | Los Angeles, CA | First Congregational | Skinner, Schlicker, Moller, David, Zeiler | 5 | 244 | 360 |

| 5 | Garden Grove, CA | Crystal Cathedral | Æolian-Skinner, Ruffatti, Diverse | 5 | 215 | 280 |

| 6 | Boston, MA | First Church of Christ, Scientist | Æolian-Skinner, Foley, Baker | 4 | 156 | 240 |

| 7 | Hanover, PE | St. Matthew's Lutheran | Austin | 4 | 184 | 235 |

| 8 | New York, NY | St. Bartholomew's Episcopal | Hutchings, Skinner, Æolian-Skinner | 5 | 164 | 229 |

| 9 | New York, NY | Riverside Church | Æolian-Skinner, Bufano, Pearson | 5 | 153 | 220 |

| 10 | Salt Lake City, UT | Mormon Tabernacle | Æolian-Skinner, Schoenstein | 5 | 155 | 206 |

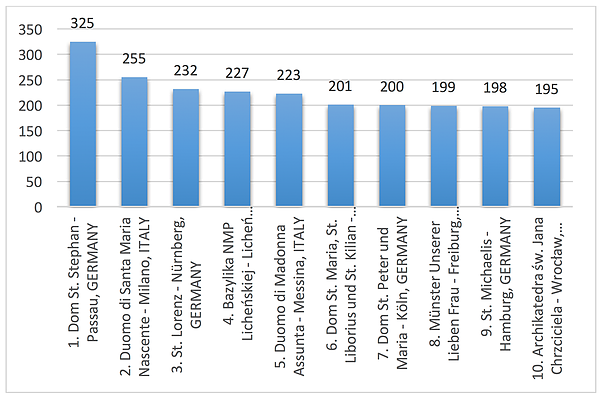

The Largest Organs in Europe

According to this methodology, the ten largest organs in Europe are as follows:

| No | City | Place | Builder | Manuals | Stops | Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Passau | Dom | Steinmeyer, Eisenbarth | 5 | 203 | 325 |

| 2 | Milan | Duomo | Mascioni, Tamburini | 5 | 186 | 255 |

| 3 | Nuremberg | St. Lorenz | Steinmeyer, Friedrich, Klais | 5 | 162 | 232 |

| 4 | Licheń Stary | Bazylika | Zych | 6 | 157 | 227 |

| 5 | Messina | Duomo | Tamburini | 5 | 160 | 223 |

| 6 | Paderborn | Dom | Feith, Sauer | 4 | 150 | 201 |

| 7 | Cologne | Dom | Klais | 4 | 144 | 200 |

| 8 | Freiburg | Münster | Rieger, Marcussen, Späth, Fischer & Krämer, Glatter, Götz, Metzler | 4 | 143 | 199 |

| 9 | Hamburg | St. Michaelis | Marcussen, Walcker, Steinmeyer, Klais, Späth | 5 | 139 | 198 |

| 10 | Wrocław | Archikatedra | Sauer | 5 | 151 | 195 |

In conclusion, six of the largest European organs are located in Germany, two in Italy and two in Poland. Also in this group the Lichen organ console is the largest. All other consoles in the European instruments classified here have five or fewer manuals. In the sacred buildings in Europe, the consoles with six manuals still qualify, along with the organs of the Cathedral in Mainz, the Basilica of Waldsassen, Germany, and the Cathedral in Palermo, but all these instruments are much smaller than the above classified and hence they are not included in the presented classification.

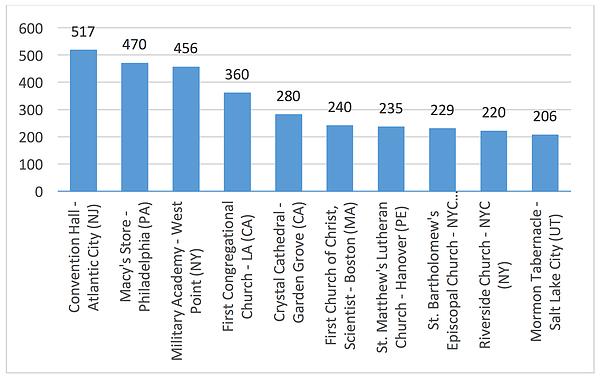

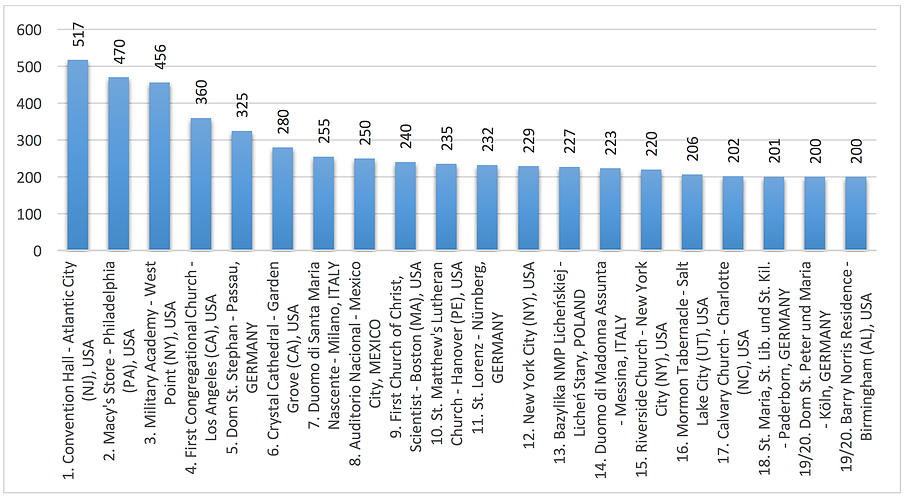

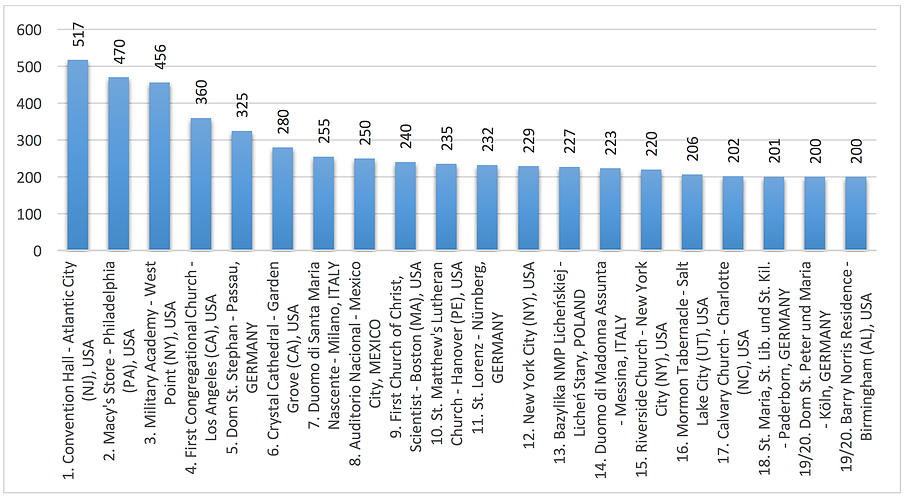

The Largest Organs in the World

After the classifications of the largest instruments in USA and in Europe, the twenty largest instruments in the world are presented below, taking into account the organs of two previous rankings:

| No | City | Place | Manuals | Stops | Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlantic City, NJ | Boardwalk Hall | 7 | 381 | 517 |

| 2 | Philadelphia, PA | Wanamaker Store | 6 | 395 | 470 |

| 3 | West Point, NY | Cadet Chapel | 4 | 382 | 456 |

| 4 | Los Angeles, CA | First Congregational | 5 | 244 | 360 |

| 5 | Passau | Dom | 5 | 203 | 325 |

| 6 | Garden Grove, CA | Crystal Cathedral | 5 | 215 | 280 |

| 7 | Milan | Duomo | 5 | 186 | 255 |

| 8 | Mexico City | Auditorio Nacional | 5 | 186 | 255 |

| 9 | Boston, MA | First Church of Christ, Scientist | 4 | 156 | 240 |

| 10 | Hanover, PE | St. Matthew's Lutheran | 4 | 184 | 235 |

| 11 | Nuremberg | St. Lorenz | 5 | 162 | 232 |

| 12 | New York, NY | St. Bartholomew's Episcopal | 5 | 164 | 229 |

| 13 | Licheń Stary | Bazylika | 6 | 157 | 227 |

| 14 | Messina | Duomo | 5 | 160 | 223 |

| 15 | New York, NY | Riverside Church | 5 | 153 | 220 |

| 16 | Salt Lake City, UT | Mormon Tabernacle | 5 | 155 | 206 |

| 17 | Charlotte | Calvary Church | 5 | 152 | 202 |

| 18 | Paderborn | Dom | 4 | 150 | 201 |

| 19 | Cologne | Dom | 4 | 144 | 200 |

| 20 | Birmingham | Barry Norris Residence | 5 | 161 | 200 |

The Largest Organs in Sacred Buildings

In European music culture, we regard the organ as an instrument closely connected with the liturgical use of various churches. Below is the ranking of the ten largest organs of the world in sacred buildings:

| No | City | Place | Manuals | Stops | Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | West Point, NY | Cadet Chapel | 4 | 382 | 456 |

| 2 | Los Angeles, CA | First Congregational | 5 | 244 | 360 |

| 3 | Passau | Dom | 5 | 203 | 325 |

| 4 | Garden Grove, CA | Crystal Cathedral | 5 | 215 | 280 |

| 5 | Milan | Duomo | 5 | 186 | 255 |

| 6 | Boston, MA | First Church of Christ, Scientist | 4 | 156 | 240 |

| 7 | Hanover, PE | St. Matthew's Lutheran | 4 | 184 | 235 |

| 8 | Nuremberg | St. Lorenz | 5 | 162 | 232 |

| 9 | New York, NY | St. Bartholomew's Episcopal | 5 | 164 | 229 |

| 10 | Licheń Stary | Bazylika | 6 | 157 | 227 |

Conclusions

After analyzing such a wide range of materials and issues related to the construction and operation of the largest organs in the world, we can draw some additional conclusions.

The beginning of the flourishing of the construction of large organs, which combines a few or a dozen divisions (which are often fully independent instruments) into one console is connected with the invention of the electric action in the second half of the nineteenth century. Mechanical and pneumatic actions had (and still have) their physical limitations when building larger instruments. That is why, in principle, all of the instruments described in this paper are based on the electric (often with upgrades) key and the stop action.

The reasons for building such large organs are, and probably will always be, divided into two groups. First, they need to fill a large room, and fulfill the desire for power and diversity; this is seen in both sacred spaces (Milan Cathedral or Basilica in Licheń Stary), and secular venues (Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, or Auditorio Nacional in Mexico City). Second are idealistic/aesthetic needs, such as increasing prestige in the eyes of the community (local or international), or the promotion of the place, like the organ in the Wanamaker Store. Wanamaker himself wanted his store to be unique, attracting customers not only through a great selection of merchandise, but also via live music, which would give customers a more enjoyable shopping experience. In unusual cases, like the Barry Norris Residence, large organs are also a hobby.

As to how such giant instruments are built, there are two ways: the successive expansion of the already existing instrument (e.g. St. Trinity Cathedral Basilica in Gdańsk-Oliwa/Poland), and creating the entire instrument from the beginning to the end according to a unified concept (e.g. Boardwalk Hall).

On the basis of case studies and my own experience, there are positive and negative features regarding the experience of playing these large organs. The benefits include the ability to perform music of every age and style, surrounding the listeners with sound naturally, the ability to shape the tone of a piece not only in terms of large‑scale registration, but also in terms of the source/direction of the sound emission, the possibility of dialogue, and the player’s ability to hear the sound fully at the console. Conversely, the issues include a delay from the moment of impact on the keys until the player hears the sound, different distances from the keyboards to the individual sections, which generates an uneven delay, discomfort when playing the extreme manuals, and faults resulting from the degree of complexity of such large organs.

Summary

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the proportions between the instruments mentioned in rankings of the largest organs in USA, in Europe and in the world. The vertical axis shows the number of rows of pipes and additional equipment managed from a single console. Labels at each bar show the number of ranks based on my methodology. This kind of illustration of the size indicator adopted in this study shows how instruments differ from one another.

Figure 1. The ten largest organs in Europe.

Figure 2. The ten largest organs in the United States.

Figure 3. The largest organs in the world.

All that being said, when evaluating musical instruments, the most important criterion is not size, but quality. In the age of many types of rankings, it is helpful to understand the many different ways pipe organs around the world can be categorized.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.