November 14, 2021

DANA ROBINSON

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Playing Schumann's Works for Pedal Piano

November 14, 2021

DANA ROBINSON

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Playing Schumann's Works for Pedal Piano

Introduction

In this interview, Dana Robinson, Associate Professor of Organ at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, discusses his recently-released video recordings of Robert Schumann's works for pedal piano with Vox Humana Editor Christopher Holman.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Professor Robinson, many thanks for agreeing to this interview. To begin, could you talk about your musical training? Did you study piano from an early age? When did you take up the organ, and what attracted you to it?

I had piano lessons as soon as I was able to read. My teacher, Hazel Cook, graduated in 1926 from the Faelten Pianoforte School in Boston, a school for all levels of piano playing, established by German pianist Carl Faelten after his 1897 demise as director of New England Conservatory. The curriculum my teacher followed there emphasized musicianship over dexterity — transposing a Mozart andante into 11 keys was just as worthy a goal as playing a Transcendental Étude; thus, I was taught to transpose and to play in all keys from the very earliest lessons. I’m grateful for that early background to this day, and it strongly influences my approach to organ teaching. My teacher also studied organ extensively with Francis W. Snow, longtime organist and choirmaster of Trinity Church in Boston and professor at Boston University. I wanted organ lessons from a very young age, and my teacher agreed to give them to me at such time as my legs became long enough to reach the pedals, which turned out to be age 11. I can’t say what attracted me to the organ — the little mission of the Episcopal Church that my parents took me to had a two-manual and pedal “Style T” Estey reed organ rigged up with an electric blower. The dear lady who played it was a “left-footed organist!” Its gutsy tones were the first “organ” sound I heard, and I was hooked.

I went through undergraduate and graduate programs in organ, all the while maintaining my interest in piano playing. (I also developed an interest in the clavichord along the way.) When I was about 20 years old, I studied for a while with a revered Boston piano teacher, Julius Chaloff. He had been one of the early pupils of the Polish pianist Ignacy Friedman, beginning in 1910 in Berlin. Prof. Chaloff exerted a profound influence on my musical thinking and carefully guided the expansion of my technical capabilities as a keyboard player. During my DMA studies in organ, I studied with Kenneth Amada, then chairman of the piano department at the University of Iowa. His approaches to music and teaching were also important influences.

Recently you've taken an interest in the pedal piano. Assuming we've never heard of the instrument before, could you tell us a little bit about its history, mechanics, etc.?

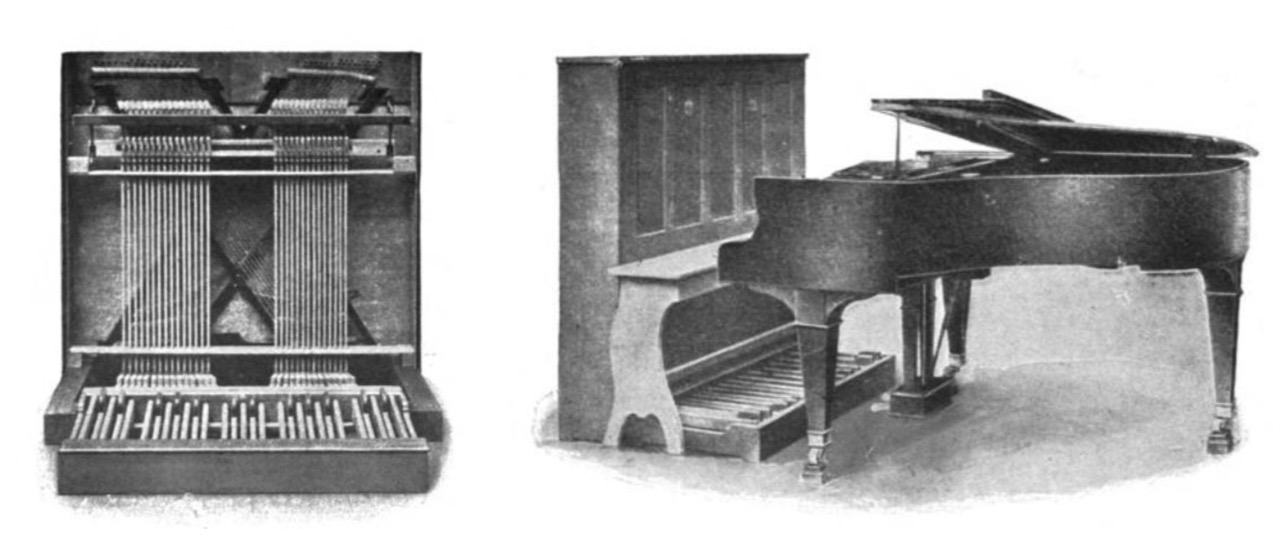

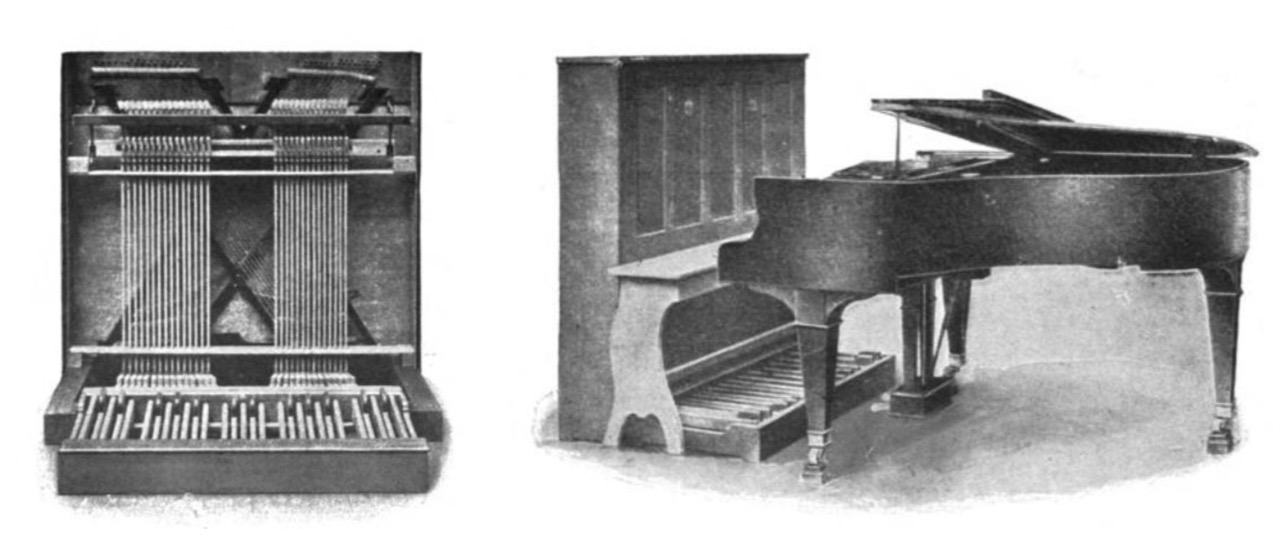

There are two types of pedal pianos: those with an independent soundboard and set of strings for the pedal keyboard, and those without, in which the pedal keys are coupled to the manual keys — either permanently or by selection. In both types, there can be options for the pedal keys to play at 16’- and 8’- , and sometimes 4’-pitch. Not all instruments come with such options. The pedal keys of my Henry F. Miller upright play only at 16’ pitch, as was the case with the instrument Robert Schumann used in the 1840s.

Examples of the independent-soundboard type are seen in nineteenth-century instruments by Louis Schöne who, according to his nephew Alfred Dolge, supplied instruments to Schumann and Mendelssohn, and instruments by, among others, Pleyel, Érard, and Pfeiffer. Independent instruments come in two upright forms: one that stands behind the player (these can be used with either a grand or an upright) and one that stands behind an upright piano. According to Dolge, Schumann’s instrument was of the latter type.

There are also independent horizontal instruments by Pleyel and others; these lie on the floor under the bench. They can be used in conjunction with either a grand or an upright piano, as shown here:

An 1890 Pleyel pédalier, played by Yves Rechsteiner.

It is this type of instrument that Martin Schmeding used for his Schumann recording, which can be found on Spotify here and Apple Music here.

Here is an older example of a Pleyel upright piano pédalier at the Cité de Musique in Paris:

There are also both nineteenth-century and modern examples in which one grand piano is placed on the floor, to be operated by a pedalboard, with another grand piano placed over it. Below is a nineteenth-century example in the same museum in Paris, where the top instrument’s damper and una corda pedals seem to be missing:

A modern example that has attracted much attention is the “Doppio Borgato”, developed by the Italian piano maker Luigi Borgato. The Italian organ-building firm Fratelli Pinchi has developed a pedalboard with accessories that can be set up to play a grand piano placed at floor level, connected with a piano placed above it in normal position. This system was commissioned by Italian pianist Roberto Prosseda, and is shown here:

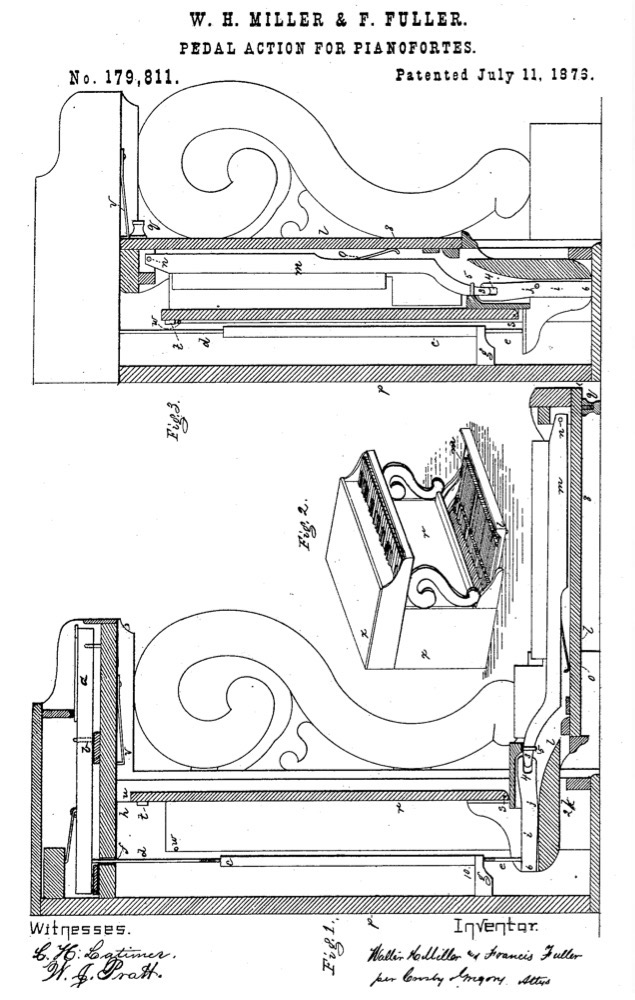

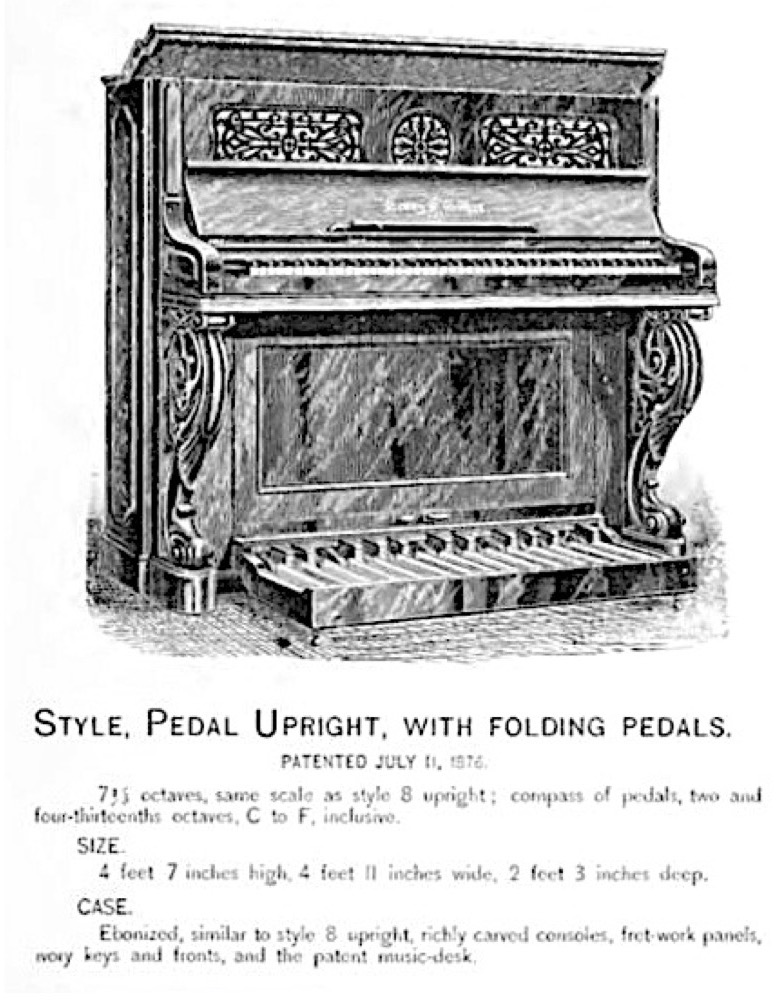

Examples of the coupling type include the Henry F. Miller uprights such as mine, the Érard grand owned by the pianist and composer Charles-Valentin Alkan, upright and grand pianos made by J.W. Brackett of Boston in the mid-nineteenth century, uprights by A.B. Chase of Norwalk, Ohio, and Pfeiffer’s retrofit system for uprights. (see Alfred Dolge’s Pianos and Their Makers for a detailed explanation of Pfeiffer’s coupling system. See Karrin Ford’s dissertation for an illustrated advertisement for the A. B. Chase upright). A full-size, parallel-strung grand pedal piano by J. W. Brackett is preserved in the instrument collection of the National Music Centre in Calgary. Although restored in the early 2000s by Jesse Moffett, this rare instrument was later damaged by flood waters and is currently neither playable nor on display in the museum.

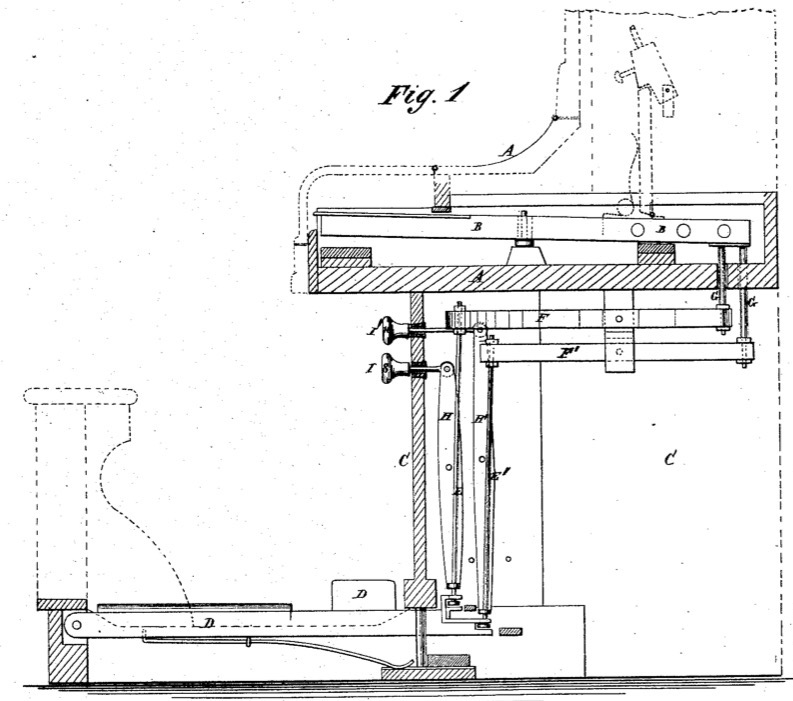

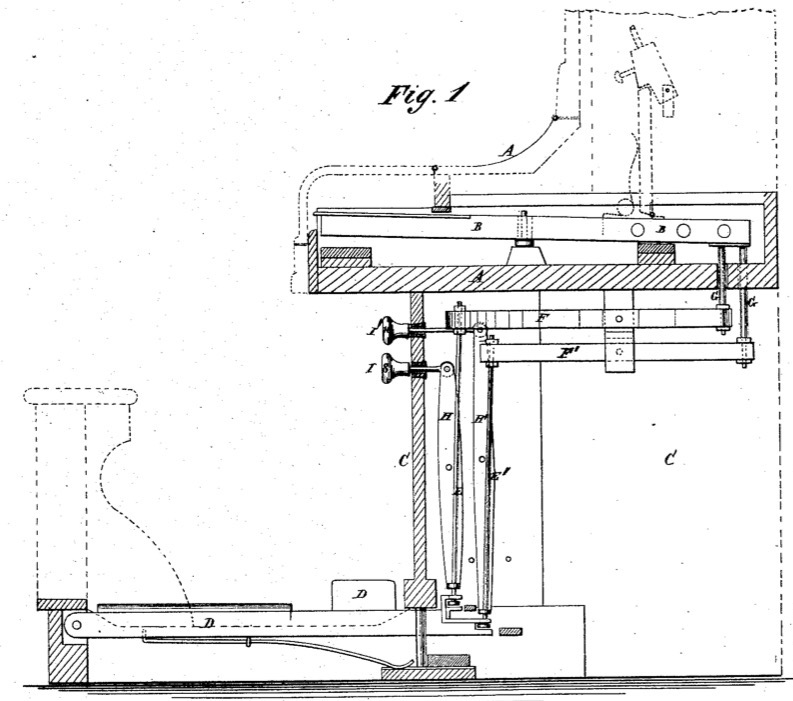

The Miller pianos are, I believe, unique in that the pedalboard is hinged so that it can be folded up into the piano case. Two sets of damper- and half-blow pedals are provided — one for when the pedalboard is open for use, and another for when it is in its folded-up position. (The operation of this system can be seen at the beginning of the video of Schumann’s op. 56 that I made, which is on YouTube — see the end of this article.) Threaded leveling feet are provided for the pedalboard. The Miller instrument does not use a rollerboard, rather the pedal keys communicate with the rear of the piano’s keysticks through a simple system of angled backfalls and stickers. It’s sensitive and reliable, and doesn’t require regulation.

Apart from the mechanical differences between these two principal types, there is a more fundamental difference between them: in the coupling-type instruments, there is only one set of strings and one soundboard for the entire instrument; thus, all tones of the instrument, whether played by the hands or the feet, communicate with each other acoustically through the same soundboard and within the same case, exactly as in a normal piano. With the independent type, there is no such communication. Furthermore, in the coupling instruments there is only one set of dampers, acted upon by one damper-pedal mechanism. Since in the independent-type instrument there is no communication between the pedal register and the rest of the piano, the effect of the damper pedal, even if it raises and lowers the dampers in both instruments in tandem, is entirely different than in the coupled type — not only due to complications that could arise from the regulation of the two sets of dampers, but also because the pedal and manual keyboards actually play separate instruments.

Many, if not most of the nineteenth-century independent-type instruments offer no possibility of operating the dampers of the pedal instrument with a damper pedal (the damper-lift rail is not even present, at least in those I know of). I find the coupling instrument to be the more elegant invention for both musical and practical reasons. Indeed, Alkan — the best-known expert player of the pedal piano, who composed numerous works specifically for it — owned a coupling Érard grand. This is the very instrument, now in the Musée de la Musique in Paris, on which Olivier Latry recorded numerous Alkan works, some Brahms and Boëly pieces, and Schumann’s op. 58, available on Spotify here and Apple Music here.

You've talked about how the pedal keys could be coupled to the manuals, either permanently or by mechanical selection. How are these controlled?

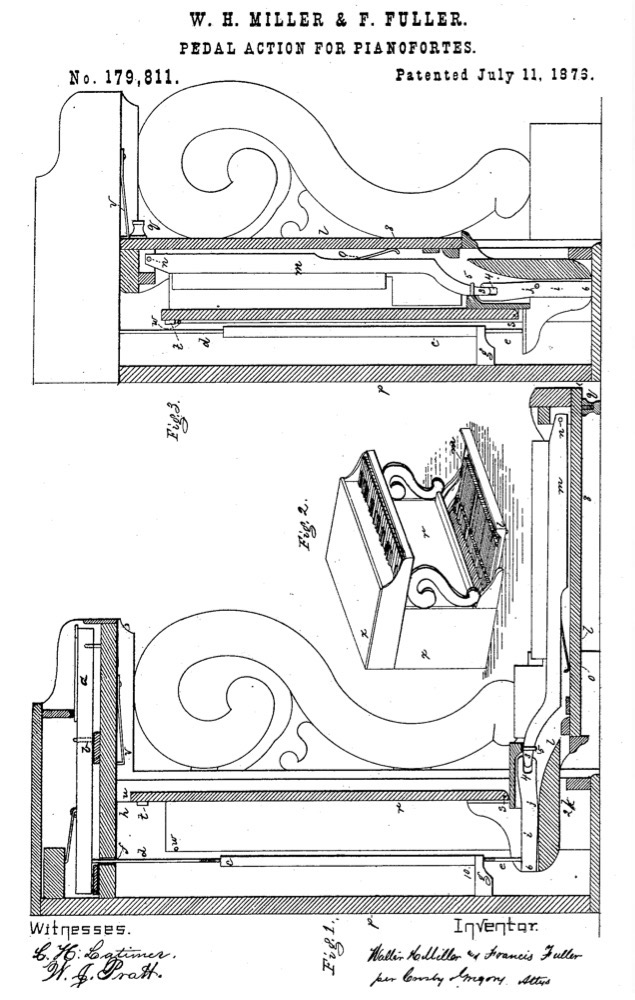

It varies according to the instrument. In the Miller piano, the pedals are permanently coupled to the manual, but the pedalboard can be disabled by means of a small “pedal check” lever located between b° and c’ of the pedalboard. In the patent application illustration from J.W. Brackett, there are two draw knobs, and based on that, I assume that the 16' and the 8' registers were available separately. Incidentally, surviving instruments by Brackett are exceedingly rare, but were apparently of high quality. George Elbridge Whiting, who taught organ at New England Conservatory and became organist of the Cincinnati Music Hall in 1878, owned one of Brackett’s uprights pedal pianos; Brackett advertised his upright instruments with Whiting’s glowing endorsement.

You recently acquired a very rare upright pedal piano by Henry F. Miller. What is the history of this instrument? How did it survive, and how did it come to be in Champaign, Illinois?

It's an instrument I've known off and on for about 45 years. When I was an undergraduate student, a classmate, Stephen Pinel (who would go on to author a number of notable books and monographs on American organ building and serve as Archivist of the Organ Historical Society) had a fascination with the nineteenth-century organs of New England. My family home was in the suburbs of Boston; during school vacations, Stephen came several times to visit so that we could go trekking around and see old organs. During one of these excursions, we went to Woburn, northwest of Boston, to see notable organs by E. & G. G. Hook — a three-manual instrument from 1860 in the Congregational Church, and a three-manual instrument from 1870 in the Unitarian Church. The former is still there, in its splendid case. I was especially interested to see the organ in the Unitarian Church, since I had never played an organ with Barker levers. When we walked in to see it, we noticed another instrument — what appeared to be a pedal piano. For me it was like seeing a unicorn! There was no one around, and since there was no bench with the piano, we took the bench from the organ and had at it (being very careful, of course!). And that was my introduction to a pedal piano. (Incidentally, the 1870 organ from the Unitarian Church is now in the Heilig-Kreuz Kirche in Berlin. I was fortunate enough to play a recital on it there several years ago.)

Well, now you have to run the clock forward about 25 or 30 years. During my first trip to Tacoma, Washington, I visited the home of David Dahl, then professor of organ at Pacific Lutheran University and Organist-Choirmaster at Christ Church in Tacoma. He thought I would be interested to hear about what he had recently acquired — an antique pedal piano. He told me that a church in Woburn, Massachusetts had closed, and that while he was there looking at the organ, he discovered a pedal piano and made an offer on it, which the church accepted. I told him, "I know that piano — I saw it 30 years ago!"

During the nineteenth century, American pianos were typically finished with a compound that degrades over time and turns black. When David and I each had first seen the piano, we had thought it had an ebonized case, but piano technician Mike Reiter realized that it was veneered in rosewood, which was being obscured by the degraded finish. David had the piano stripped and refinished, and it now looks much as it would have when new.

A couple of years ago, David decided that a grand piano would suit his needs better than the pedal piano. Knowing that I had some history with the Miller piano — and that I had coveted it for years — he sold it to me, and I brought it to Champaign, Illinois. Although the piano was in excellent condition, I decided to have the hammers replaced, since the original felts had hardened to the point where they wouldn’t hold their voicing for more than a few days at a time. Several of the nine copper-wound unison bass strings were dead beyond all hope of resuscitation, so I had them replaced with appropriate duplicates. The original steel-wound bichords and plain wire trichords remain. The soundboard, bridges, and action are all original.

Beyond compositions for pedal piano, how was the instrument used in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and how have you used your pedal piano in the present day?

You can use the piano in two ways: you can use it to play any keyboard music, including pedaliter organ music, or you can play pedal-piano music — but there isn't much of that. The pedal piano works that interest me most are the two Robert Schumann sets — only about thirty-five minutes of music, but music of the utmost beauty and imagination. The Alkan works are challenging and distinctive; however, Alkan specifies “double” and “simple” in his scores, indicating that 16’- and 8’ registers are called for both separately and together. As I mentioned, my upright plays 16’ alone all the time, so often, the Alkan pieces aren’t ideally suited to it. Alkan’s pedalboard also extends to contra A, while my instrument only extends to great C. There are several pieces by Gounod, including two pedal-piano and orchestra pieces and a piece for small ensemble with pedal piano. I have only been able to look at the concerto, and it doesn’t hold much appeal for me. I use my instrument to practice organ music, along with the Schumann sets and whatever other music I can find to adapt to it. You’d be surprised, for instance, how good Buxtehude’s e-minor Chaconne sounds — you can play that piece like a "left footed organist" while operating the damper pedal with the right foot, and it's very charming. Nothing like Buxtehude would have heard it, of course, but it’s nonetheless beautiful. I wouldn’t practice it that way to prepare an organ performance, but I can learn much about the piece by trying it that way.

I've experimented with some other music — Franck arranged his Prelude, Fugue and Variation for harmonium-piano duo, and of course, there’s Harold Bauer’s lovely transcription for piano solo; the arpeggios in the variation are a natural fit for piano with plenty of damper pedal. I’ve arranged the work for pedal piano, incorporating elements of Franck’s duo version and Bauer’s solo version. It’s quite satisfying to play. Some of the Brahms organ works are also very attractive on the pedal piano, lending themselves to playing more or less without adaptation. Much of the difficulty lies in figuring out how to incorporate the use of the damper pedal — so necessary for a musical sound in Brahms’s piano music, just as in the works of Schumann. I haven’t yet tried to tackle Liszt’s Ad nos fantasy, for which pedal piano was originally indicated along with organ, but I might have a go at it one of these days. Beyond that, there is new music I haven’t yet investigated — something for me to look forward to.

I think that through much of its history, the pedal piano has been regarded as a utility instrument — a sort of “practice machine” for organists — but if one regards the instrument this way, one will never obtain anything other than a “utility” musical response from it. That’s never satisfying. If we practice organ music on the pedal piano, the instrument can reveal a great deal about the potential for shaping melodies, motives, and harmonic patterns. If your pedal technique doesn’t enable you to control dynamics the instrument is very unforgiving — even more unforgiving than a pedal clavichord, due to its greater dynamic range. Any false move in pedal playing with the pedal piano results in a painfully obvious, ugly accentuation. Such false moves in pedal playing might be concealed to a certain extent at the organ, but they’re never desirable — an organist wants to be able to control timing, pipe speech, and release to the fullest extent.

The easy way around the problem is just to play everything uniformly loud with hands and feet alike, but taking that approach, one would never learn anything about how the music could be shaped, which is one of the greatest benefits to be derived from practicing organ music on the pedal piano.

That immediate touch-sensitivity is also what makes the pedal piano such a powerful teaching tool with respect to pedal technique. In playing pedal parts, both legs must be optimally aligned for every interval. That means any repositioning of the feet must be accomplished from the center of the body outward, using the trunk muscles to pivot the pelvis on the bench to bring the legs into alignment. You can never use your feet to push into the pedal keys for leverage to reposition yourself, as many organists are used to doing. Whatever shortcomings or failings you might have in organizing your pedal playing become immediately apparent on this instrument — you might think you're doing it right, but the instrument informs you that you’re mistaken! Also, with an upright, there's quite a bit of potential mechanical noise — since the pedal-keyboard linkage is contained within the hollow recesses of the instrument, any abrupt or uncontrolled release of a pedal key results in a drum-like “thump” resonating in the piano case. The same goes for a careless release of the damper pedal.

You have recently recorded the Schumann works for pedal piano: the Six Studies, Op. 56, and the Four Sketches, Op. 58. These works are mostly performed on organ today. What are some of the issues and questions you've faced when playing these on pedal piano?

Beyond the general considerations I mentioned when playing the pedal piano, a question arises as to what extent it is appropriate to use the damper pedal. I have assumed that Schumann did not have a universal damper lifting mechanism for his pedal instrument, thus, the damper-pedal effect would have been available only for music played by the hands. There also would have been no resonance between the pedal unit and manual unit on Schumann's instrument. But for me, this didn't make any difference — I had the music and I had an instrument, and I had to figure out what musical possibilities it afforded. Besides, I’m not convinced from any accounts that Schumann actually attained any real proficiency at the pedal piano.

Schumann stated in a letter that the opportunity to compose for the pedal piano "at once gives the composer a significant increase in power and richness, and a quantity of new effects to hand. So then, since the player is hindered in using the pedal [meaning the damper pedal or the sordino], it seems to me, above all, a beneficial means for attaining a clear, correct, rendition. Finally, in itself, it leads to Bach, to the study of his organ compositions, since now not everyone is able to have an organ. This threefold usefulness might well be worth further discussion." Reproduced and translated in Robert Schumann, Works for Pedal Piano and Organ, ed. Arnfried Edler, trans. Margit McCorkle (Mainz: Schott, 2009), 131–132.

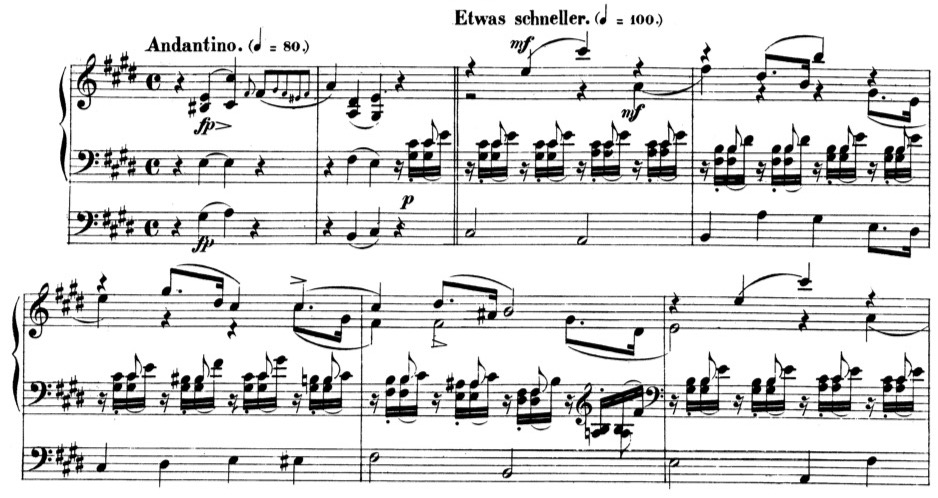

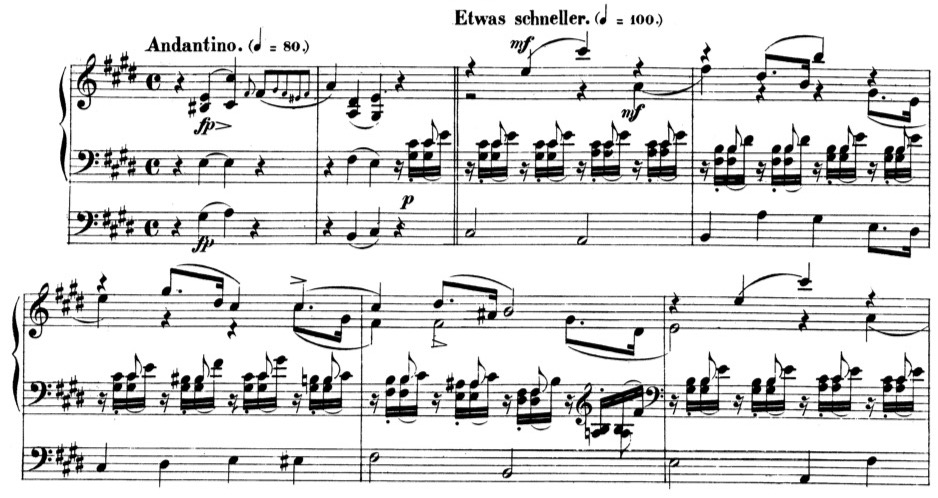

Schumann seems to say that difficulty precludes the free use of the damper pedal. But I can't accept a dry, pedal-less sound as ideal for much of this music — although it’s perfect for things like the many homophonic, staccato passages in the Four Sketches. When Schumann was arranging publication, he had the publisher indicate that the pieces could be played either on the pedal piano, or by three or four hands on normal pianos. Well, no pair of pianists would ever sit down at a piano and play these pieces without the full, unrestricted use of the damper pedal. That said, Schumann also explored the possibility of textures uniquely available on the pedal piano. For example, in the Study 3 in E Major he writes staccato sixteenth notes in the tenor and alto registers, while the right hand plays the canonic voices, and the pedal has sustained lines in longer notes. This effect would be unattainable by a solo pianist at a conventional piano.

The opening to Third Study for Pedal Piano, Andantino — Etwas schneller, by Robert Schumann, played by Dana Robinson on the Henry F. Miller pedal piano.

But there are other cases where an unrestricted use of the damper pedal seems to be musically indispensable, for example, the Study No. 4 in A-Flat Major, which remained a favorite of Clara Schumann. She often played it as a solo piano piece, obviously relying on the damper pedal to connect the bass notes. Her pupil Adelina de Lara recorded the work as a two-hand piano solo, using the damper pedal liberally throughout, and arpeggiating chords to be able to catch the bass notes:

The opening to Fourth Study for Pedal Piano, Innig, by Robert Schumann, played by Adelina de Lara, c. 1951.

It seems to me that the piano sound Robert Schumann imagined in such a piece must have involved the unrestricted use of the damper pedal, regardless of whether he was able to realize that at his own instrument.

The opening to Fourth Study for Pedal Piano, Innig, by Robert Schumann, played by Dana Robinson on the Henry F. Miller pedal piano.

As I first studied the pieces, I experimented with avoiding the damper pedal altogether, using it only in the two places Schumann indicates it — once to sustain an arpeggio, and once at a cadence — but I quickly became dissatisfied with that. So I tried to look for ways I might incorporate the use of the pedal throughout the music. The first thing I learned was to operate the damper pedal with the left foot while playing with the right — not so difficult for us organists, I think, as we so often have to use the left foot to operate a Swell shoe or a piston. As time went by, I discovered that I could play a certain number of keys with a heel and reach the damper pedal with the toe of the same foot. I found this to work not only with a number of natural keys, but with several sharps, as well. So the possibilities began to present themselves, to the point where I was able to play most of the music with the use of the damper pedal as I imagined it should sound. A few spots in the Schumann proved especially tricky when it came to managing the damper pedal while playing the bass line, such as the little fugal section of op. 56, no. 6, and the trio of op. 58, no. 3. By coincidence, while I was working all this out, I stumbled upon an organ method book by G. E. Whiting’s pupil Henry Morton Dunham, which features a whole set of pedal exercises devoted to the use of the heels on the sharps. It was a new technique for me, but apparently not for my nineteenth-century Boston forebears!

Whether I could do the same things on any other pedal piano would depend on the dimensions of the pedal keys, the position of the damper pedal etc. And, of course, if you have an instrument with the independent pédalier unit such as one of the old Pleyels, you can't do as much, since the pedal notes aren’t connected to the damper pedal. If I were to think of an ideal concept for a new instrument, it would be a coupling instrument with the damper-pedal operated by a treadle-bar spanning the entire compass of the pedalboard, and thus accessible to either foot from any key.

With the exception of no. 5 in b minor, the Six Studies in Canonic Form seem to demand far more extensive use of the damper pedal than the Four Sketches, which are characterized by so much homophonic, staccato texture. Interestingly, Schumann wrote both sets at the same time and had originally thought to publish them together in a shuffled order. Ultimately, he decided to separate them into two suites, each very different in character, but uniquely beautiful. To me, the grouping within the suites seems just right — each piece seems to flow naturally into the next. In a letter to his publisher, Schumann states that it might be appropriate to indicate the Four Sketches as suitable for the organ, but not the Six Studies. Indeed, the only way I find any satisfaction with the Six Studies on the organ is when they are arranged as duets, enabling the two canonic voices to be played on contrasting or complementary sounds. Paul Tegels and I have enjoyed performing them in such an arrangement for many years. I have played the Four Sketches as organ solos numerous times.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Editor's Note

Dana Robinson has released two video recordings of the Schumann works for pedal piano, which can be viewed here:

Robert Schumann: Six Studies for the Pedal Piano, Op. 56

Movements begin at the following times:

0:20 I. Nicht zu schnell

2:42 II. Mit innigem Ausdruck

6:48 III. Andantino — Etwas schneller

8:52 IV. Innig

12:54 V. Nicht zu schnell

15:33. VI. Adagio

Robert Schumann: Four Sketches for the Pedal Piano, Op. 58

Movements begin at the following times:

0:19 I. Nicht schnell und sehr markiert

3:50 II. Nicht schnell und sehr markiert

7:45 III. Lebhaft

12:43 IV. Allegretto

Vox Humana offers our special thanks to Dana Robinson, John Minor of The Piano Shop in Champaign, Illinois for his preparation of the Henry F. Miller pedal piano, and Frank Horger for the video and audio recordings.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.