March 28, 2021

LENORA McCROSKEY

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

French Alternatim Performance Practice

March 28, 2021

LENORA McCROSKEY

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

French Alternatim Performance Practice

Detail of Charles Wild: Choir of the Cathedral of Amiens (1823), depicting the choir accompanied by a serpentist.

Detail of Charles Wild: Choir of the Cathedral of Amiens (1823), depicting the choir accompanied by a serpentist.

Introduction from the Editor

In this interview, University of North Texas Professor Emeritus of Organ and Harpsichord Lenora McCroskey discusses her decades-long research on alternatim practice in the French baroque period with Vox Humana Editor Christopher Holman, focusing on the many varieties of vocal music that would have been sung in alternation with seventeenth and eighteenth century French organ works.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Professor McCroskey, many thanks for agreeing to this interview. To begin, could you talk about your musical training? Did you study piano from an early age? When did you take up the organ, and what attracted you to it?

There were many musicians in my family, mostly amateurs; my grandfather learned shape notes at the singing schools in North Carolina, and my mom majored in piano. I started piano lessons when I was eight, but I was really fascinated with the organ. When we moved to Tennessee, there was a Hammond where my mom was the organist; I got to mess around with the bars and the buttons, and we played lots of piano organ duets. Then we moved to Florence, South Carolina, where I got my first organ lessons, but kept up piano as well.

I studied at Stetson University under Paul Jenkins, who took four of us students to Europe in the summer of 1964. After the grand tour of organs, we ended up in Haarlem for the Summer Organ Academy, where I took classes from Anton Heiller and Gustav Leonhardt. I also met Larry Palmer in the harpsichord class — and I'd never played a harpsichord in my life! I was bowled over by the knowledge those men had of the historical background of the pieces that we were working on. I came back and wanted to go into musicology.

After graduating from Stetson, I went to Harvard University, but after a week, I discovered that musicology wasn't quite what I thought — I had expected studies in performance practice! After a difficult semester, I decided to stay. I finished my master's degree, but I really wanted to study harpsichord. Gustav Leonhardt took me for a year in Amsterdam. And then, after that year, I was asked to come back to Stetson to teach as a sabbatical replacement for Paul Jenkins.

After that I moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts for seven fabulous years in a wonderful assistant job, at Harvard Memorial Church. Then I applied to the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York; I was hired as a teaching assistant in harpsichord and studied organ with Russell Saunders. After I finished my doctorate, I got the job at the University of North Texas, in Denton, where I’ve been ever since. I retired in 2009, but love Denton.

One of your areas of specialization is French baroque organ music, and for many years now you have studied and collected sources of vocal music that would have been performed in alternatim. What exactly is this alternation practice, and how did it come into being?

Simply put, it's musical alternation between two groups. These can be two choirs, a priest and choir, organ and choir, and it can even be an instrumental ensemble and choir. I say choir, but it could be a solo singer or a group. The first reference to "alternatim" I know of is around the fourteenth century in Italy, but it existed all over Europe. Everyone did it, but it lasted in France longer than anywhere else, and French Baroque organ music is intimately tied to alternatim performance. Quite frankly, I think it was purely practical: to give the singers a break. On holy days, they had so much to sing — morning services, masses, more Offices, on top of a big vespers before the feast day.

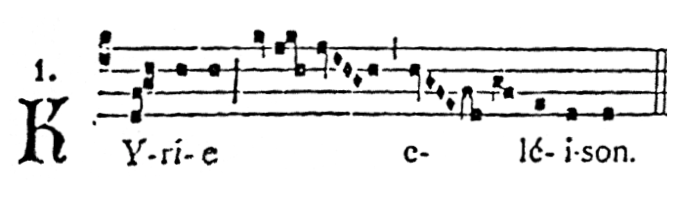

In the Mass, the Ordinary parts that were performed in alternatim were the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and Ite, missa est (the Credo was not). The text of each is divided in portions, called versets, and the organist plays the first verset, the choir sings the second, the organist the third, and so on. To be a bit clearer, to perform a Kyrie with plainchant, the organist would play the first Kyrie eleison, then the singers would sing the second Kyrie, then the organ plays the third Kyrie. The singers then sing the first Christe eleison, the organist plays the second, and the choir sings the third; then for the final Kyrie, it alternates organ, choir, organ. Dividing up the parts of the mass, it looks like this:

Kyrie

Organ: Kyrie eleison I

Choir: Kyrie eleison II

Organ: Kyrie eleison III

Choir: Christe eleison I

Organ: Christe eleison II

Choir: Christe eleison III

Organ: Kyrie eleison I

Choir: Kyrie eleison II

Organ: Kyrie eleison III

Gloria

Choir/Priest: Gloria in excelsis Deo

Organ: et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Choir: Laudamus te,

Organ: benedicimus te,

Choir: adoramus te,

Organ: glorificamus te,

Choir: gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam,

Organ: Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Choir: Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe,

Organ: Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris,

Choir: qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis;

Organ: qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Choir: Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Organ: Quoniam tu solus Sanctus,

Choir: tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe,

Organ: cum Sancto Spiritu: in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Sanctus and Benedictus

Organ: Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus

Choir: Dominus Deus Sabaoth.

Organ: Pleni sunt cæli et terra gloria tua.

Choir: Hosanna in excelsis.

Organ: Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.

Choir: Hosanna in excelsis.

Agnus Dei

Organ: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Choir: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Organ: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Ite, missa est

Priest: Ite, missa est.

Organ: Deo gratias.

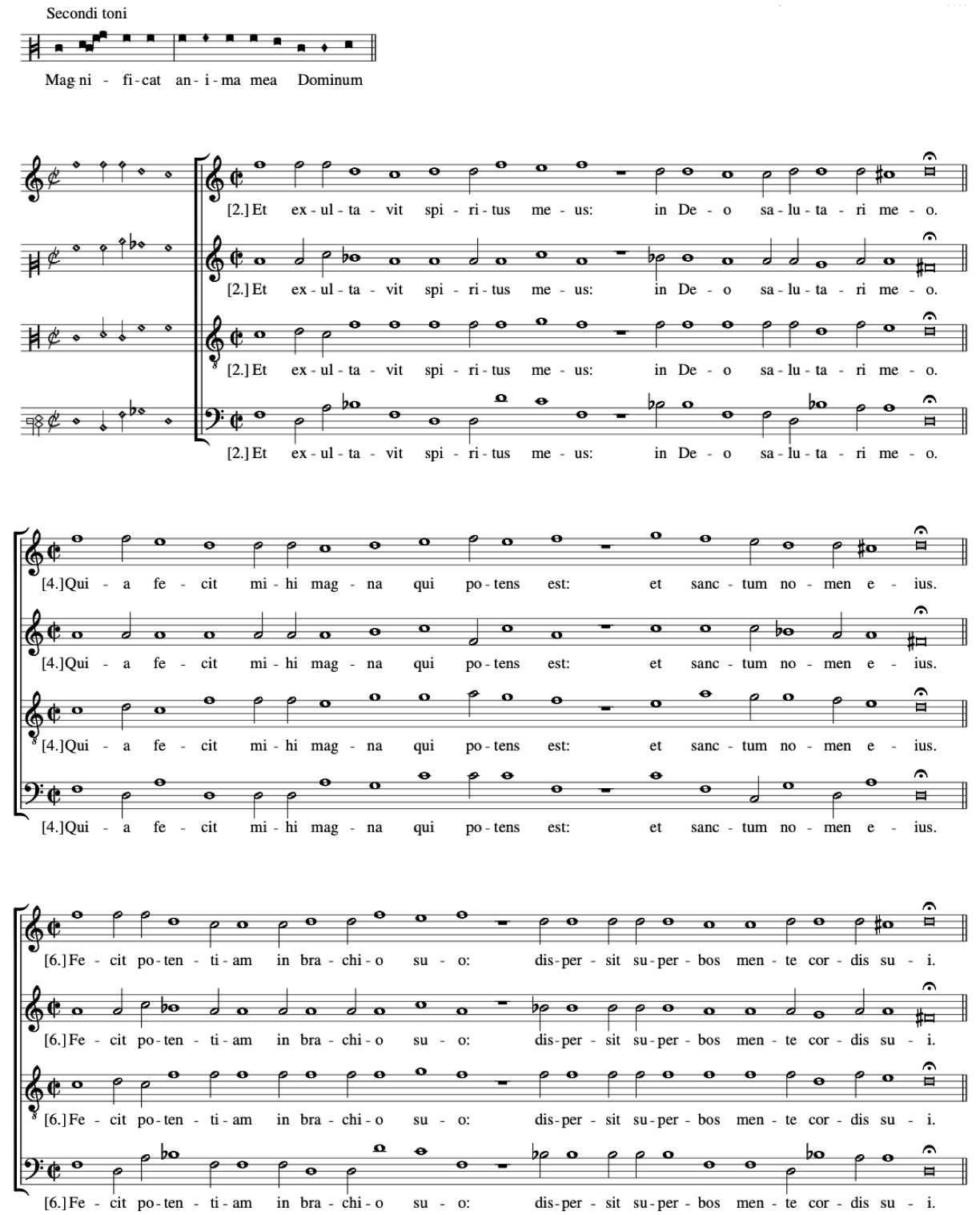

In vespers, it was the Magnificat and the hymn that were sung this way. In the former, the singer would begin with the Magnificat antiphon of the day, then begin the first verset on whatever tone was prescribed, then alternate each verse. With the hymns, the organ played the first stanza/verset, the choir the second, then the organ the third, and so on. Here's how the Magnificat was divided:

Choir: Magnificat antiphon for the day

Choir: Magnificat anima mea Dominum;

Organ: Et exultavit spiritus meus in Deo salutari meo,

Choir: Quia respexit humilitatem ancillae suae; ecce enim ex hoc beatam me dicent omnes generationes.

Organ: Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est, et sanctum nomen ejus,

Choir: Et misericordia ejus a progenie in progenies timentibus eum.

Organ: Fecit potentiam in bracchio suo; dispersit superbos mente cordis sui.

Choir: Deposuit potentes de sede, et exaltavit humiles.

Organ: Esurientes implevit bonis, et divites dimisit inanes.

Choir: Suscepit Israel, puerum suum, recordatus misericordiae suae,

Organ: Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros, Abraham et semini ejus in saecula.

Choir: Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto,

Organ: Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper: et in Saecula saeculorum. Amen.

Choir: The same Magnificat antiphon for the day would be repeated

In organ masses, determining which plainchant setting to use can be straightforward; for instance, the chant mass "Cunctipotens genitor Deus" is quoted in the pedal in the first organ versets of the Gloria in excelsis in both Nicolas de Grigny's Livre d'orgue and Couperin's Messe pour les Paroisses. For many church musicians, though, the first point of reference when looking up a plainchant hymn are the nineteenth and early twentieth century editions by the monks at Solesmes, France (e.g. Liber usualis, Graduale Romanum, etc.). Are these and the performance practice their editors describe representative of what someone like Couperin or Clérambault might have heard?

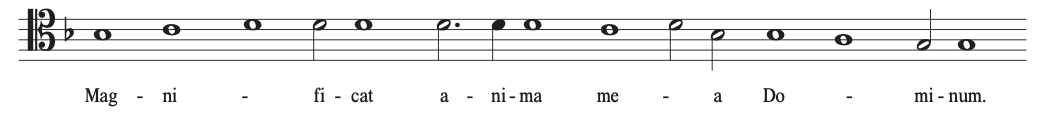

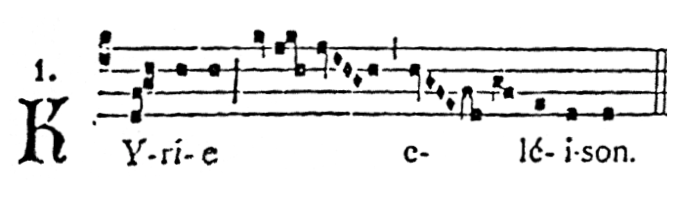

In short, no. Guilliaume-Gabriel Nivers was a priest who published several chant books, including several graduals, which covers the masses (the Bibliothèque nationale de France has digitized several editions, which are free here: 1687, 1696, and 1697, and the Antiphonale for the offices. He simplified the chant by taking out some of the melismas. His chants are also rhythmized — there are note values: longs, breves, and semibreves (which in modern notation translate, at least proportionally, to whole, half, and quarter notes, respectively), and they do fit the natural emphasis of the text as the French heard it. Here's the first verset of a Magnificat from Nivers's 1694 Antiphonarium monasticum:

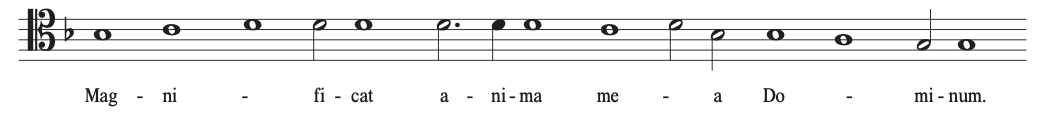

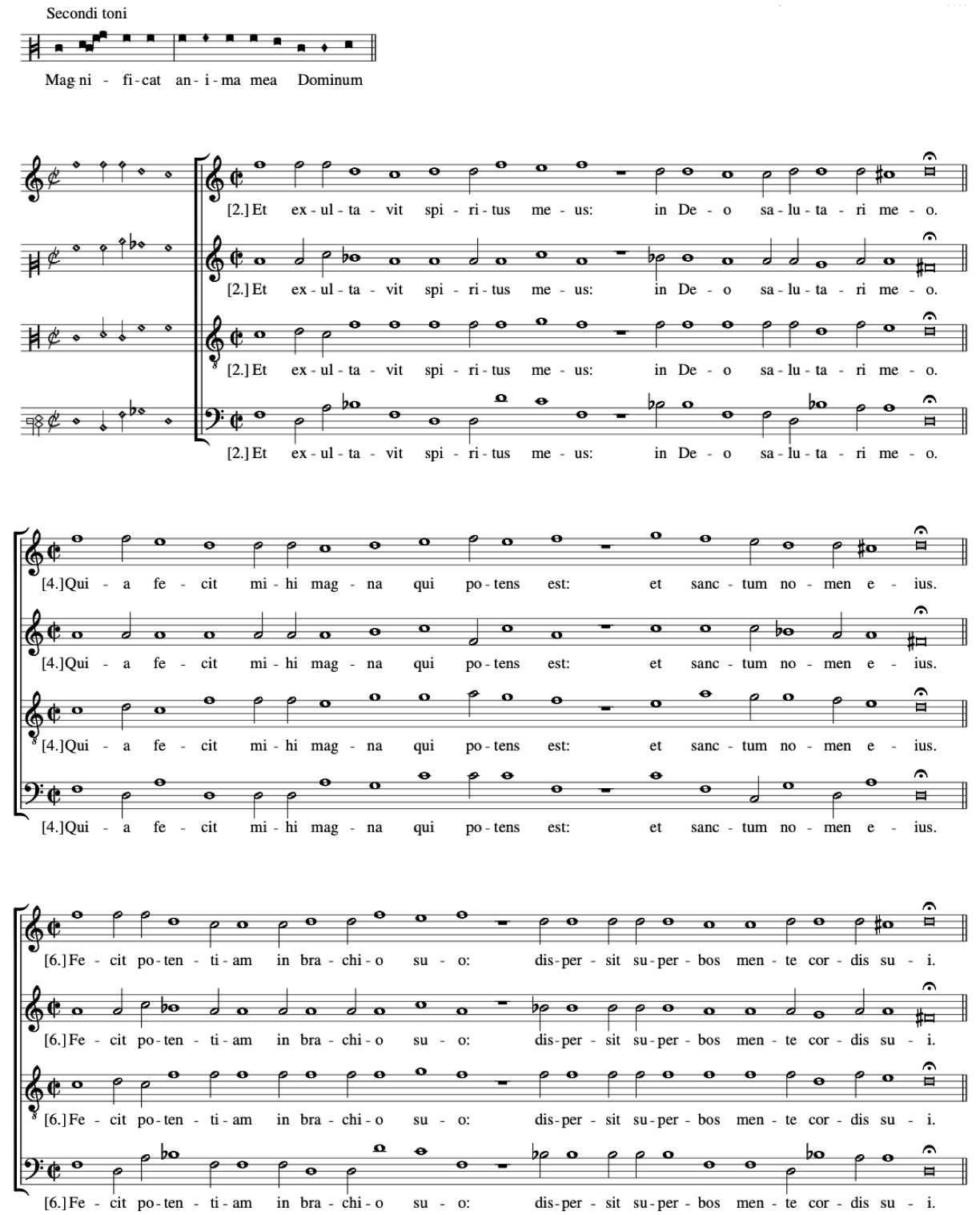

There's also quite a bit of polyphonic music, which is actually what caught my attention first. It's not your fanciest Palestrina motet by any means — it's simple, and it's often syllabic. Here's the transcription of Magnificat vocal versets by Jean de Bournonville:

It's syllabic and simple, and I think it's really quite beautiful. It also matches the length of many organ versets — not Nicholas de Grigny (his music is pretty special). Many of the other organ settings that we know and love are simple and work well with this music. I know that people are going to want to perform de Grigny in alternatim, but I haven't found much vocal alternatim music that's quite on that level.

Nivers-style plainchant works very well in organ masses like the Couperin Messe pour les Paroisses, the Grigny Mass, etc. What did they use for organ versets that are in a more tonal (major/minor) system, like the Couperin Messe pour les Couvents?

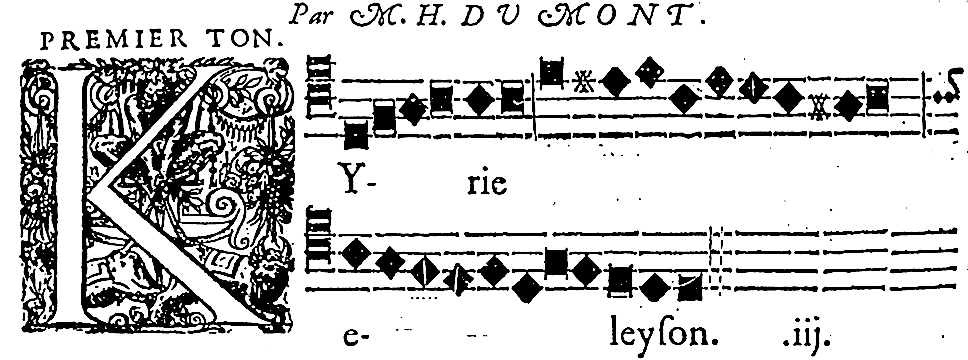

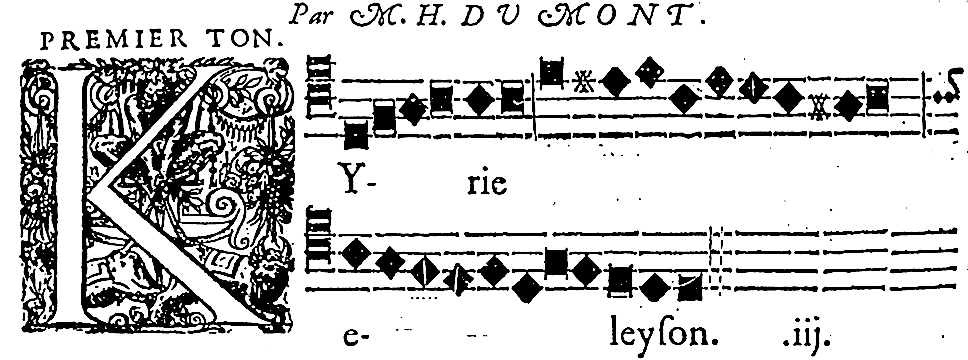

For those, you can go to places like the Bibliothèque nationale de France's website, Gallica, and search for "plein-chant musical." Henri DuMont's composed plainchants are the most famous and are available here. You can sing those with organ versets that are more in the major/minor system. One of them, the Messe Royale, was quite famous and for decades could be found in various Roman Catholic liturgy books, including the 1903 Solesmes edition of the Paroissien Romain. The editors, however, felt they had to make DuMont look like Gregorian chant — compare the 1701 printing versus that of Solesmes:

Curiously, I have only found one other organ mass that is based on a specific chant, an anonymous organ mass found in Almonte Howell’s collection entitled Five French Baroque Organ Masses, which is based on a Nivers plein-chant mass.

Fauxbourdon, a sort of harmonized plainchant, was also sung. Are there any written collections or manuscripts of fauxbourdon?

Not really. The Bournonville above is similar, where chant is in the tenor and the other parts in fourths and fifths above. Fauxbourdons aren't hard to write, but you have to know the rules. Interestingly, in many of the hymn settings in these polyphonic vocal versets, it's fairly common for the chant melody to be missing. Of course, the organ would have played the chant, and everyone knew the chant — the choir was singing them all the time! So I think it wasn't difficult at all for them to improvise polyphony around that melody.

The other form of vocal verset that we haven't yet discussed is chant sur la livre, the improvised harmonization of plainchant. Abbé Jean Prim has written an excellent article about it (available here), but otherwise the academic community has stayed deafeningly silent about this topic. What can you tell us about this lost art?

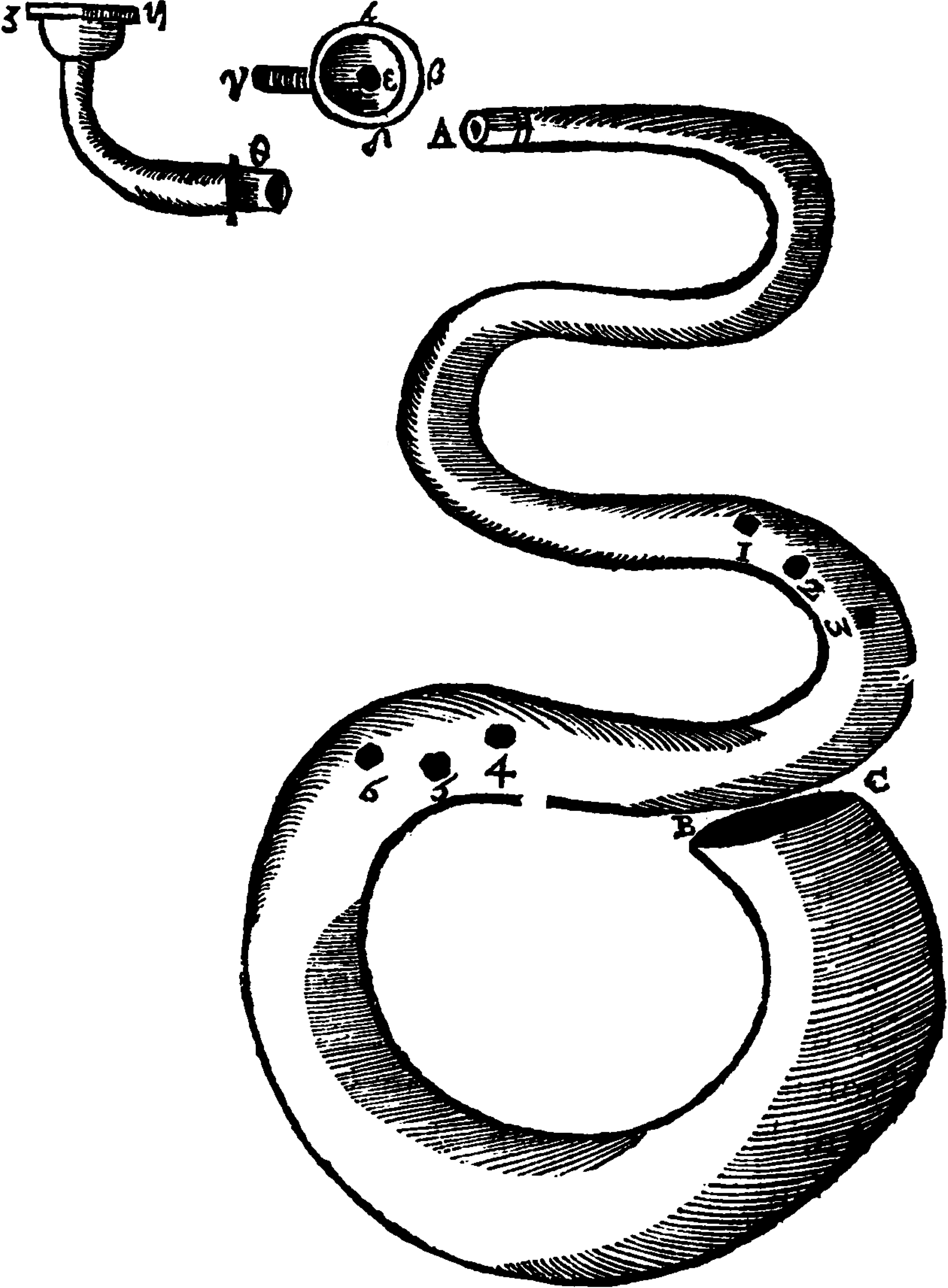

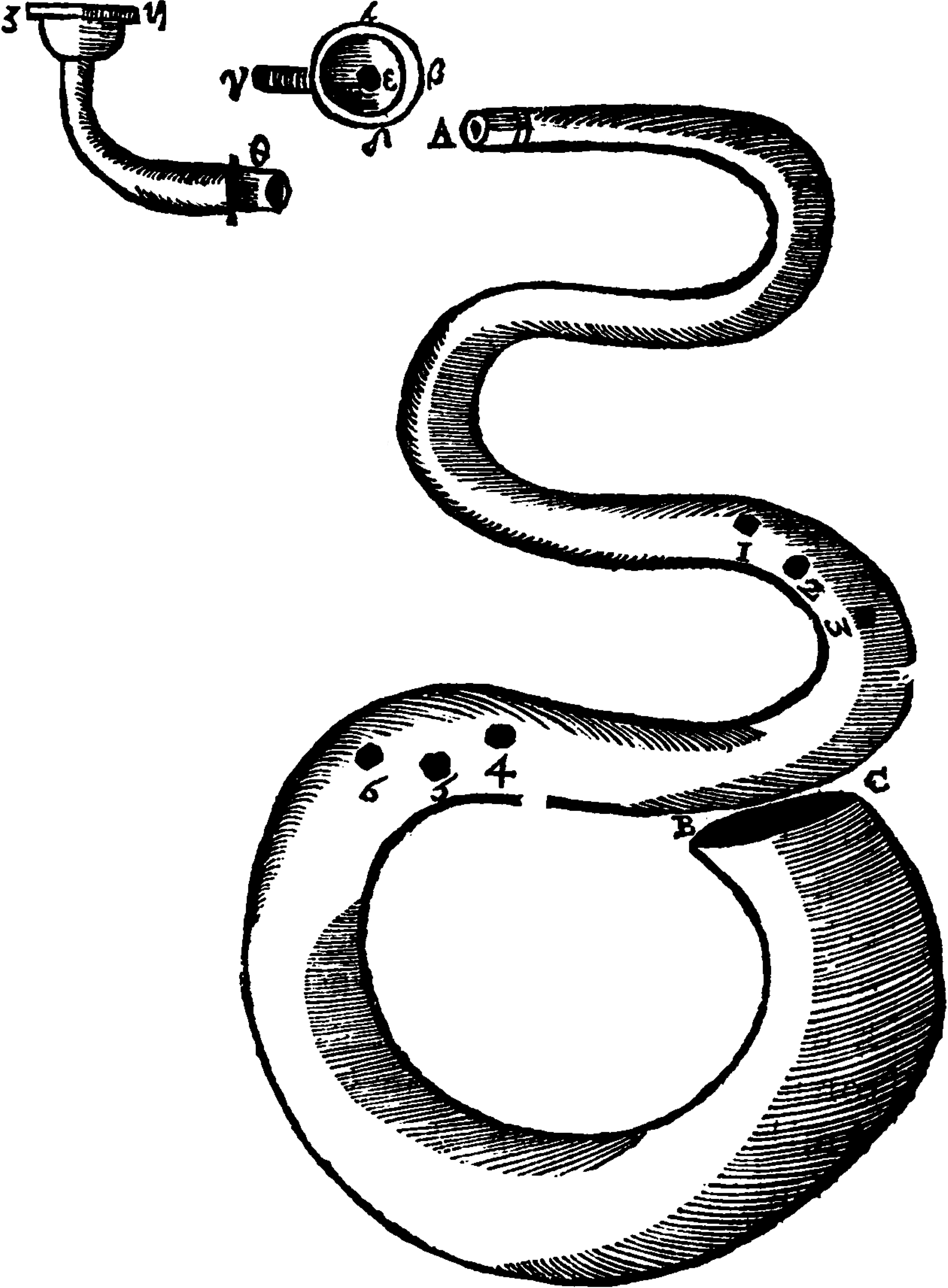

It is very interesting, but there isn't that much surviving information about it. From descriptions, the chant melody was sung in long tones, possibly with a serpent [the instrument] doubling, then one or two singers would improvise above it. So if you know your chant and you're a good vocal improviser, go try it some time! Chant sur la livre was performed fairly commonly, and not only in Paris.

Do you think performing organ music in alternatim today, for instance in liturgies, is something worthwhile, or is it a relic of the past?

I think you would need to choose carefully so you don't overstep the clergy! And there are cautions in French baroque period ceremonials that say not to play too long! But that aside, I think alternatim practice is really beautiful. And because the organ music is so fabulous, it's tempting to play a long string of organ pieces, beautiful as they are, all together. But I think it's even more special to link them with what they were paired with at the time of composition, particularly for anybody who's interested in history. Why not? I mean, it's beautiful. And boy, we need some beauty these days!

How can we find some of these vocal alternatim versets in a format that doesn't require a lot of time and expertise to interpret?

I'm working on a collection of this music, which will be published by Wayne Leupold Editions. It will include much of the material I mentioned, with settings specifically to be performed with the famous organ versets like the Couperin and de Grigny masses, as well as those by Titelouze, Nivers, Louis Couperin, etc. There are organ hymns, masses, and magnificats that are seldom performed that could be quite effective with simple vocal music.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Prior to her appointment at UNT, Dr. McCroskey, was on the faculties of Stetson University, the Longy School in Cambridge, and the Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester, and was the Associate Organist/Choirmaster in the Memorial Church at Harvard. She holds the BA and BM degrees from Stetson, where her organ study was with Paul Jenkins; an MA from Harvard in musicology; and the DMA from the Eastman School of Music, where her organ study was with Russell Saunders. She studied harpsichord with Gustav Leonhardt and continuo with Veronika Hampe at the Amsterdam Conservatory in the Netherlands.

As a professional player, she was founder or cofounder of Baroque ensembles in Cambridge, Rochester, and Fort Worth. She is currently the keyboardist for the Denton Bach Players. She has also played continuo for the Dallas Opera, the Dallas Bach Society, Ars Lyrica Houston, Dallas’s Orpheus Ensemble, Musica Poetica, and many others. She now serves as accompanist for the Denton Bach Society and is Director of Music at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Denton.

Active in the Dallas Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, she has served as Dean, director of various committees, and as district convener for North Texas. She has won numerous grants for study in France, including a John Anson Kittredge Foundation grant; is a fellow of the Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute (now the Radcliffe Institute) at Harvard; and was awarded the Paul Riedo Award by the Dallas Bach Society for service to early music in north Texas.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.