May 20, 2018

CRAIG CRAMER

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Catholic Church Music, and Organs at the University of Notre Dame

May 20, 2018

CRAIG CRAMER

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Catholic Church Music, and Organs at the University of Notre Dame

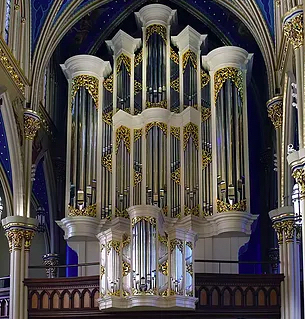

The 2017 Paul Fritts & Co. organ at the Basilica at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana.

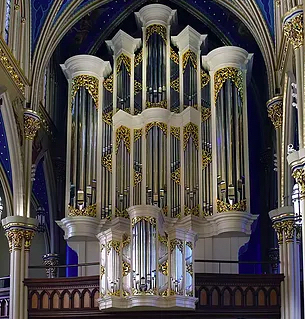

The 2017 Paul Fritts & Co. organ at the Basilica at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana.

Introduction

Craig Cramer, Professor of Organ at the University of Notre Dame, discusses the tremendous new organs at Notre Dame, recruiting strategies for a university program, and current trends in Catholic church music in the U.S. with Vox Humana Editor Christopher Holman.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Prof. Cramer, many thanks for agreeing to this interview. To begin, could you talk about your musical training? Did you study piano from an early age? When did you take up the organ, and what attracted you to it?

Many thanks for this opportunity. I was raised in a small town near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. When I was young I followed the typical progression of piano lessons followed by organ lessons when I started high school. I practiced in my home parish on a seven-rank Möller and thought that I had died and gone to heaven! Then on to Westminster Choir College as an undergraduate followed by graduate work at the Eastman School of Music. I was always struck by the sound of the organ. It is so colorful and multi-faceted. As with many young people, I suppose, I was also fascinated by the mechanical aspects of the organ.

You maintain a major international performing career, and have played on some of the world’s most important organs. But with playing so many diverse kinds of organs, how do you design your programs?

Perhaps this is a naïve goal, but I try to use the whole organ in any program that I play. I try to take into account the particular stylistic focus of whatever organ I am playing, and then I think about how to show off as much of the instrument as possible. Even though they are beautiful, principal choruses become wearing on the ears, especially for non-musicians who might be attending the concert. Variations sets are very effective vehicles for showing off many aspects of an organ. On the great historic organs upon which I have been fortunate to perform I try to pay attention to the wind characteristics and how the wind allows me to shape the sound. I think just having vast experience with old organs makes you keenly aware of the wind. Working with the wind and how it relates to the touch is fun and revealing! I tell my students that the performance organs on campus are the best teachers that they will ever have. Planning good programs takes time, since one naturally also wants to take into account loud and soft, fast and slow, different composers and style periods, and everything else that goes into making the program an enjoyable listening experience.

Your career has encompassed just about everything an organist can do. You have been teaching at the University of Notre Dame, co-organized the most recent Westfield Center for Historical Keyboard Studies Conference, you play recitals all over Europe, and have fifteen recordings to your credit. What has this been like, and how do you balance work with personal time?

I have indeed been very fortunate in my career. For 33 years I was married to a very understanding person who really understood what I did and encouraged me. Gail was herself of course a great organist, and despite the difficulties of maintaining her own high-level position at Notre Dame and caring for our two young sons, she never complained when I was away. So, the most important thing to say is that I was very fortunate in my private life. Second, Notre Dame faculty teach light loads, and in exchange a lot is expected of our faculty development. In the case of a musician, of course, a visible performing and recording career stands in as our research. No one here ever looked over my shoulder and told me that I was gone too much or that I had to tailor my career in a certain way. For that I am very grateful.

Perhaps musicians are the luckiest people in the world because in general our work and our hobbies are the same thing. I tell my two sons all the time to stand up at my funeral and say that I never worked a day in my life, and that is true. Despite the usual frustrations of committee work and bureaucratic nonsense that we all have in our jobs, on balance I have to say that I have been fortunate in this regard. It has all been fun, especially teaching and working with my wonderful students.

The main focus of my playing career has been the great historic organs in Europe, especially in Germany and The Netherlands. One of the most rewarding things in my professional life has been taking students on organ study tours. We have been all over northern Europe, and it has been great fun. That experience has tied into the graduate organ literature course that I taught for many years, and of course playing old organs caused my students’ playing to improve and deepen in ways that I could not imagine before we started going to Europe.

The University of Notre Dame has recently commissioned and acquired several tremendous organs, including two major instruments by Paul Fritts & Co. and an Italian baroque organ. How did these instruments come to be at Notre Dame, and what was your role in the process?

The Fritts organ in north German style in the organ hall of the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center arrived in 2004. My vision was to have two organs in this building. The larger of these — a more eclectic instrument in the concert hall — was not possible because of budgetary limitations. Instead, we had to wait for the Basilica organ project, which Gail started in 2005. After her death, Dr. Andrew McShane, the director of music and organist at the Basilica, took over the project and did a brilliant job seeing it through to completion. I was the consultant (in a non-voting capacity) on the Basilica Fritts organ. This is a very successful project, and the marriage of acoustic and organ in both of these situations is remarkable. We now have contrasting instruments, and we feel that someplace on campus we can play nearly all of the organ literature in a historically-informed way.

The Fritts organ in the Performing Arts Center was a project that I worked closely on with Paul Fritts, the acoustician, and the architects. It all worked together, and there was a great sense of common purpose and cooperation that was inspiring. The hall is magnificent with four seconds of reverberation, and the organs (Fritts in the front and a seventeenth-century Italian organ in the back) seem to hover and float in that marvelous acoustical environment. It has been a dream, and recruiting students into our programs became much easier when this facility became a reality.

The Italian organ is on loan from a private individual. I hope that it will be acquired by the university because it is wonderful in the splendid acoustic of the organ hall. Of course we have all learned a great deal from this organ, which has a short octave and is tuned in quarter-comma meantone. It is a joy to play, and the students have really taken to it and broadened their horizons considerably as a result.

We now have fifteen organs on campus, only one of which has electric action. In the past year we have significantly added to and upgraded our practice organs. We are moving into a new music building in January 2018. In addition to the two new practice organs for that building, we are also getting a Taylor and Boody portative organ that will enhance our organ and choral programs at the university. It is all very exciting, and I am grateful to the visionary leadership of the past two deans, the chair of the department of music, and to Margot Fassler, director of Sacred Music at Notre Dame. These colleagues have completely understood my vision for building a great organ program at Notre Dame, and together I think we have made major strides towards realizing that goal.

Recruiting students is a major consideration in university organ programs. What are your strategies? In your experience, do different approaches appeal to undergraduate versus graduate students?

At Notre Dame I teach nine graduate students and hold a performance class once per week. The load is very light relative to most of my colleagues in the field. Notre Dame is one of the 15 wealthiest universities in the U.S. in endowment. Every graduate student in the university receives at least a tuition grant. Our organ students get a stipend in addition to free tuition, so it is a very attractive offer from a financial standpoint. Our program is one of the most competitive in the country. This year we had 25 applications for three slots in the Master of Sacred Music degree. So, we are in the fortunate position of being able to make offers to the best of the best, and I am very grateful for that. Recruiting students at Notre Dame involves three things: the monetary support, the programs into which we recruit (Master of Sacred Music and Doctor of Musical Arts), and one of the finest collections of organs in the country. We are very fortunate, and I am happy to report that ours is one of the thriving organ programs in the country.

Things are very different at the undergraduate level. We describe our undergraduate music majors as “walk-ons.” We cannot recruit them because first they have to be admitted to the university. Many times we have recruited very talented players only to see them be rejected by the university. The opposite is the case as well, of course. Fortunately, our undergraduates as a group are among the best and brightest in the country, and so usually we get very fine players. Since ours is not a school of music, and we are not a conservatory, our situation is different than many of the schools with whom we recruit at the graduate level. We have had as many as six undergraduate organ majors; at present we have two very talented guys, both of whom are juniors.

Do you see any trends in the job market for organists over the next few years, especially for those pursuing Catholic church music? Do you have any advice for young organists wishing to work primarily in Catholic churches?

I cannot speak authoritatively about other denominations or universities, but there are regularly many more full-time positions that are open than we can fill, especially ones in Roman Catholic parishes. The advice that I would give to an aspiring church musician is to sing, sing, sing! Learn Gregorian chant, the basis of all music. If you can sing musically, then you can learn counterpoint, you can learn to play a keyboard instrument, and you can conduct. Our profession is crying out for people who are musical, for people who can lead in the broadest sense, and for people who have a deep-seated passion for making music in the liturgy.

Do you have any new recordings or forthcoming publications?

My latest recording was on the magnificent Ehrlich organ in Bad Wimpfen, Germany. The organ was built in 1747. It is not a large instrument and has no manual reeds, but it is a thrilling sound and plays a surprising amount of literature very well. Before that was the recording that I made on the large Fritts organ at St. Joseph Cathedral in Columbus, Ohio.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.